At Home/On Stage chronicles the intrinsic role of media technology in the formation of identity

In a small second-floor gallery at Cantor Arts Center, At Home/On Stage charts a rich legacy of Asian diasporic communities and their visual representations. One of three inaugural exhibitions from Stanford’s Asian American Art Initiative, it examines public and private spaces in Asian American life through archival photographs and artistic works, chronicling the intrinsic role of media technology in the formation of Asian American identity, beginning with the first major wave of immigration during the 1800s. From early cartes-de-visite to multichannel video installation, At Home/On Stage presents an incisive rendering of Asian America through the lens of media history.

The stereotyping and marginalisation of Asian Americans undergirds the exhibition’s contemporary selections. Stephanie Syjuco’s standout Afterimages (Interference of Vision) (2021) is an intentionally crumpled archival photograph of three Filipino Igorot dancers. The original image, used to promote the 1904 St Louis World’s Fair, advertised a Filipino ‘human zoo’. The pictured figures are folded on each other and obscured from view, an act that simultaneously calls attention to the violence of the initial display while foreclosing contemporary access to the dancers’ faces and bodies. In Miljohn Ruperto’s Appearance of Isabel Rosario Cooper (2006–10), the artist collages clips from films that featured the eponymous midcentury Filipino American actress, blurring out any other figures in the frames. Cooper’s ‘appearances’ are brief – she twirls in a dance hall, recites a line to a scene partner. Both Syjuco and Ruperto emphasise the marginalisation of their Asian-American forebears, offering ways to negotiate this history without recreating its harm.

The documentary photography by Asian Americans casts a light on diasporic community, homing in on twentieth-century negotiations of the medium. In one astonishing print produced by 1920s San Francisco-based May’s Photo Studio, a composite portrait includes family members located in both China and America, collaged together in a single scene. One man, clothed in a black blazer and tie, sits next to a young boy who wears a Chinese tangzhuang, or Tang suit. Michael Jang’s 1970s series The Jangs explores the cultural milieu of Chinese-American life via images of the artist’s family: Study Hall (1973) shows a group of children browsing a range of popular print media, from Archie comics to mad magazine. Here, American cultural products obscure – both literally and figuratively – the individual faces of Jang’s family members. In these photographs, immigrant communities develop singular relationships to mass media, forming an artistic space that encapsulates the Asian American household.

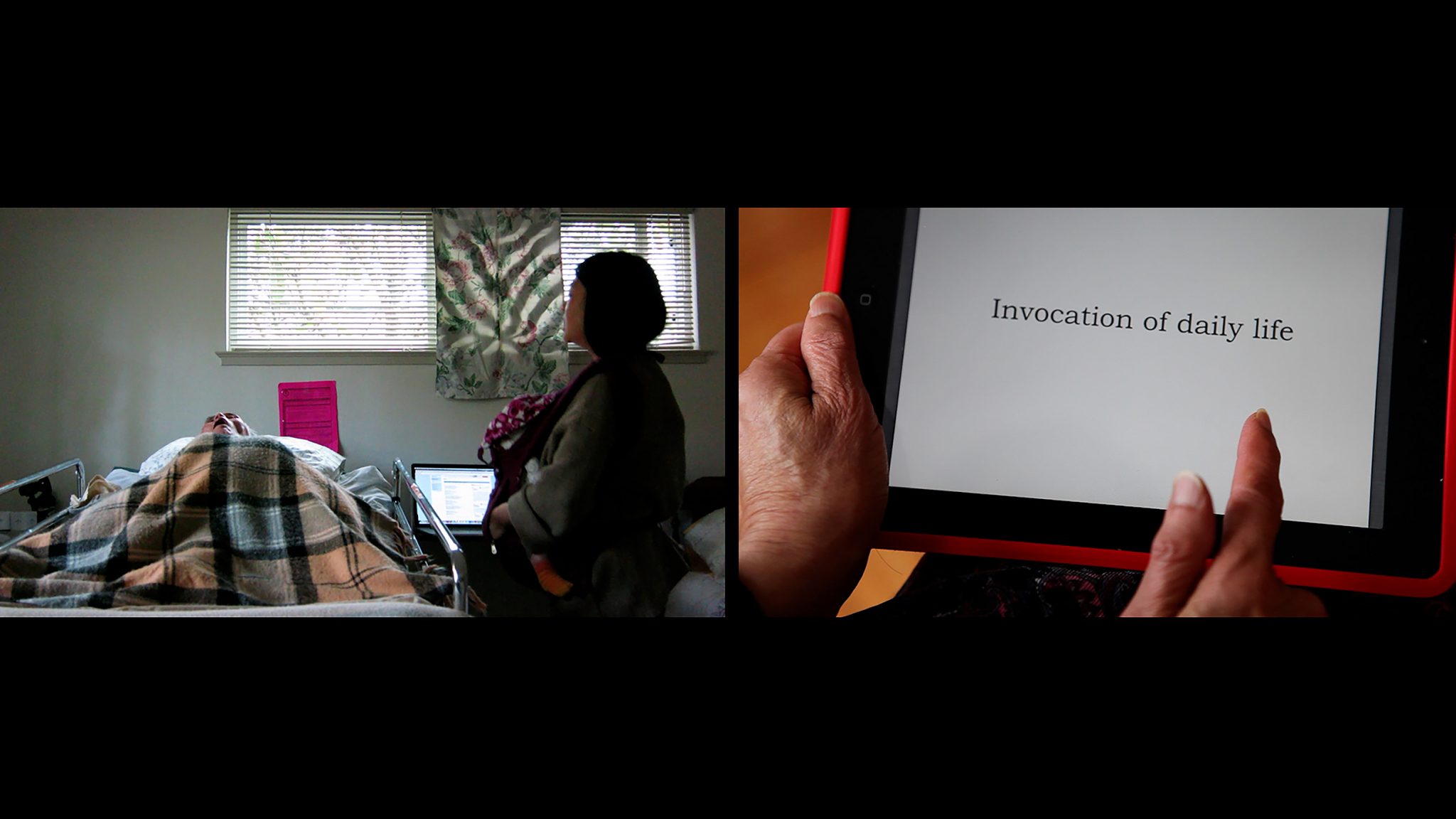

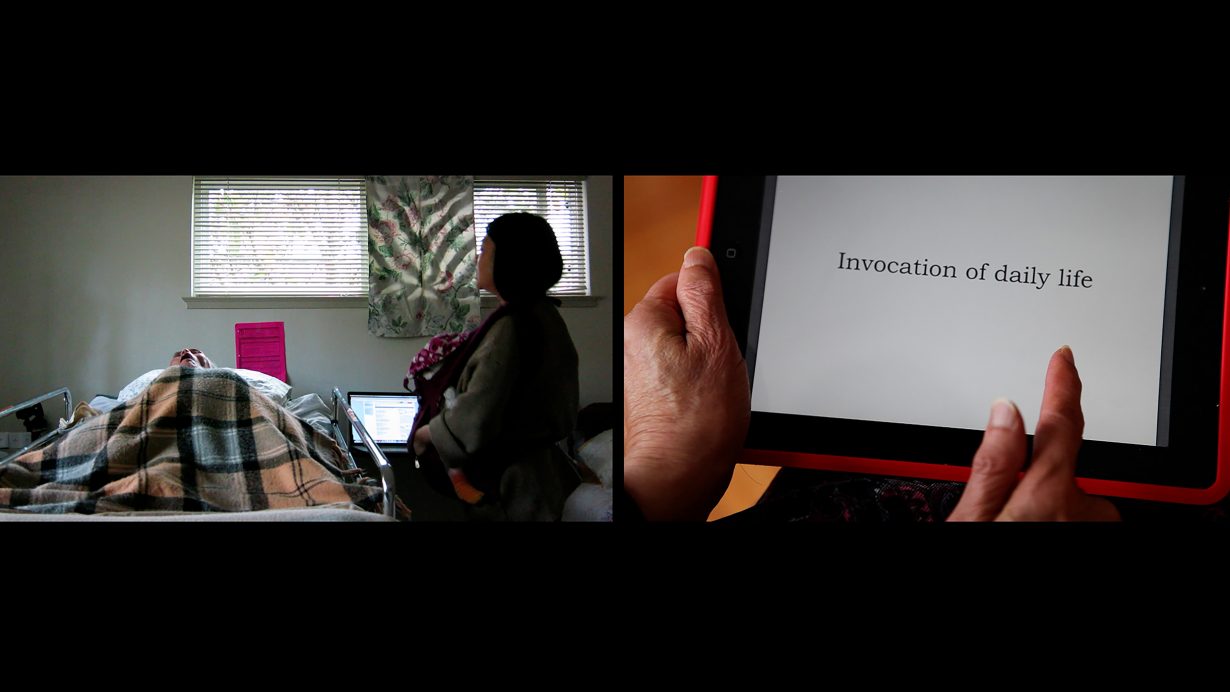

An equal investment in fatigue and death matches the occasionally lighthearted tone of the exhibition’s domestic portraiture. Patty Chang’s Que Sera Sera/Invocations (2013–14), a two-channel video installation, shows the artist holding her baby while singing to her father in hospice care. Another screen reveals an iPad, which Chang’s mother scrolls through while reading a series of unusual prayers: “invocation of vocal cord paralysis” follows an “invocation of artificial respiration”. Opposite Chang’s film, Reagan Louie’s photographs are especially resonant: in Jiao, Shenzen, China (2017), a vivid colour print depicts the artist’s best friend, Jiao, on a couch. The accompanying photograph, Jiao, Hefei, China (1980), presents him in a similar pose, on a bed with his eyes closed. Chang and Louie’s works capture moments of exhaustion that converse with the exhibition’s focus on violence and displacement.

This penetrating look at media and identity investigates the ramifications of oppression in the Asian American community, a heritage embedded in the museum itself. Indeed, there is an elephant in the room – or just off the lobby, where two permanent exhibitions laud Leland Stanford Sr’s family history. Stanford, the university and museum’s founder, oversaw the construction of the American transcontinental railroad, a project that depended on the underpaid labour of roughly 15,000 Chinese Americans, an estimated 1,200 of whom died due to hazardous working conditions. In an age of institutional apologia, At Home/On Stage feels both refreshing, in its particular focus on artwork by Asian Americans, and circumspect, unable to acknowledge Stanford’s exploitative practices. As I left the museum, I thought of one of Chang’s incantations, an “invocation of bureaucratic waste”. The artists included here challenge Stanford’s legacy, even if the institution does not.

At Home/On Stage: Asian American Representation in Photography and Film at Cantor Arts Center Stanford University, Palo Alto, through 15 January