Is Masamune Shirow one of the most influential artists you don’t know?

In October 1970, the British mathematician John Horton Conway revealed a groundbreaking game designed to be run without players (a ‘zero-player’ game) in the pages of the popular-science periodical Scientific American. Titled ‘The Game of Life’, this mathematical ruleset could be demonstrated on graph paper or animated via a computer interface using a geometric grid and coloured squares, or ‘cells’, to simulate occurrences of ‘life’, ‘death’ and the serpentine possibilities of self-replication. According to Conway’s system, solitary cells would die through ‘loneliness’, while cells surrounded by too many others risked perishing from ‘overcrowding’. If the conditions were just right, however, and a cell had the mutual support of two or three live ‘neighbours’, it would find itself ‘born’ into this abstract world and thus subject to its own journey of ‘evolution’. This thought experiment was built upon postwar scientific interest in self-replicating systems such as crystal formation and the question of whether machines might reproduce unaided. Although visually crude, it developed its own captivating image of ‘cellular automata’ – a concept that would cause significant repercussions in the fields of biology, computational science and philosophy, but perhaps most unusually, in a unique tributary of the lavish visual dreamworlds of postwar Japanese manga.

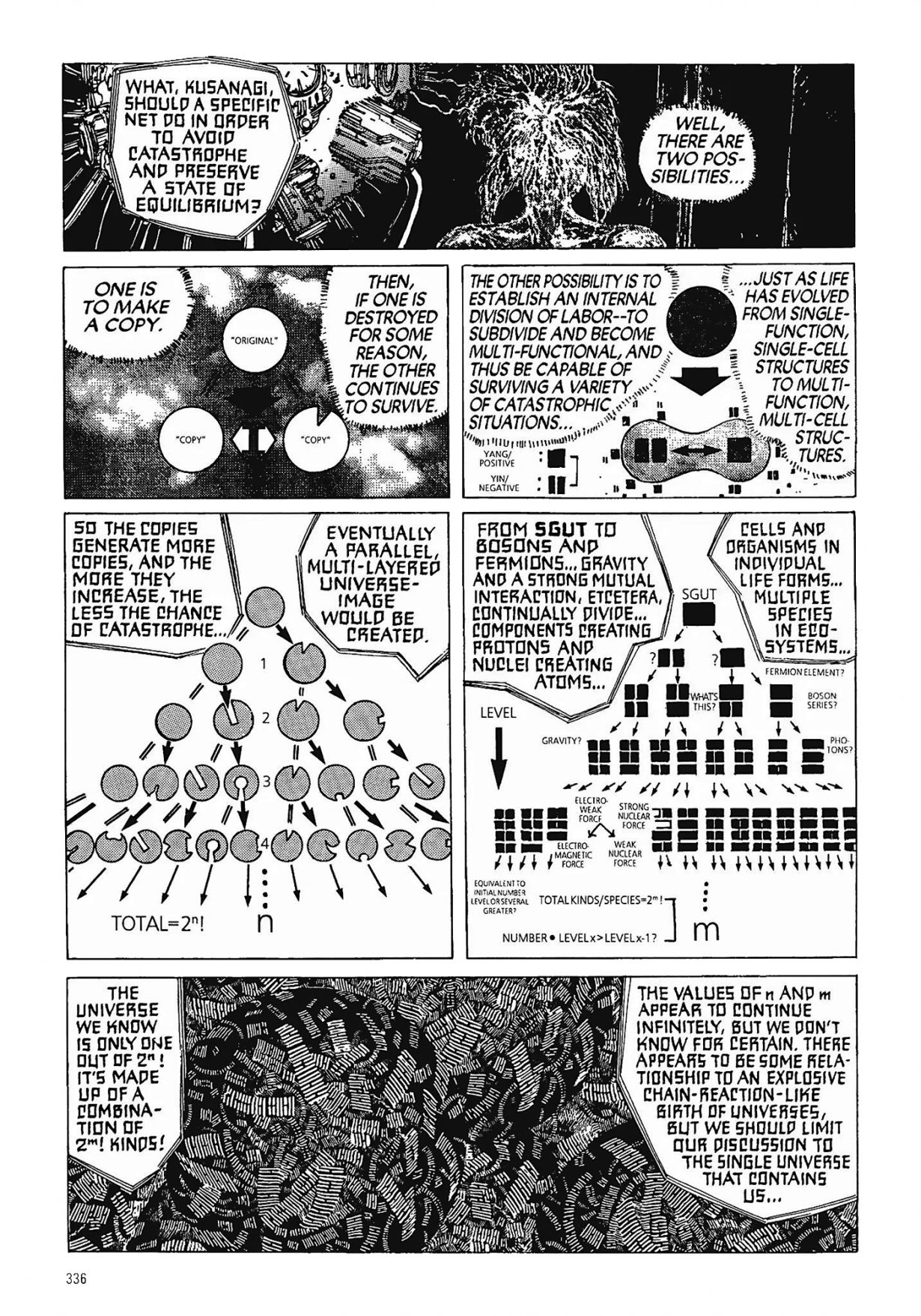

Back during the early 1970s, as an avid reader of Nikkei Science (the Japanese edition of Scientific American), Kobe-based amateur artist Masamune Shirow would find himself deeply influenced by his encounter with the game’s evolutionary trajectories. These would set the tone for his genre-defining experiments in comics depicting a technologically accelerated world that continue to shape science-fiction imaginaries today. His cyberpunk fantasies of Venusian artificial intelligence, militarised police-states, corrupted utopias and transmigrating consciousness in manga such as Black Magic (1983), Dominion (1985–86), Appleseed (1985–89) and, most famously, Ghost in the Shell (1989–90) didn’t simply stage automata, emergence and self-replication as the set-dressing of uninspired genre dross. At their very best, they actively integrate them into a unique hybrid of cybernetic comic and technical manual, where the predictable panels of sequential art mutate into bruised motherboards of thickly lined goofball cartooning, intermeshing seamlessly with neural maps, technical annotations and digital collage. It’s a bracing style, and it allowed Shirow to map the various metastases of an accelerated capitalism, where neofeudal governments might adopt heavyhanded tactics to counter the threat of weaponised wetware and deregulated networks.

Shirow would notably paint some of his most dramatic scenes in inks and watercolours – a cyborgian security officer dissolving into a liquid haze of thermo-optical camouflage against a Tokyo skyline, for example – crashing traditional media into vertiginous encounters with the image world of science fiction. This, in turn, echoed his writing’s twinned obsession with technological momentum and the persistence of the human belief in spirit and soul. Later works, such as Ghost in the Shell 2: Man-Machine Interface (1997) would even take the form of bizarro schematics, in which the floating identities of networked consciousness inform both developments in plot and graphic effect, allowing the book’s story to unfold in the interstices between physical infrastructures and virtual applications. When the franchise’s protagonist, Motoko Kusanagi, chooses to fuse with an autonomous ‘consciousness’ she uncovers within the endless data streams of the net, Shirow’s comics reconfigure themselves as neural lattices of electronic pulsation and information flow. These images are a far cry from the graphic simplicity of Conway’s ‘Game of Life’, but they’re actively sustained by the same fundamental interest in how complex systems such as intelligence and information might develop and propagate. They appear to derive their narrative dynamism from the same exploratory energy, unfolding haphazardly like viral cells replicating in a Petri dish until they attain structure and cohesion.

It was the appearance of Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy in 1951 that kickstarted a comics preoccupation with ensouled robots, metal shells harbouring human vitalities that would refocus Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio myth for the postnuclear age. Later, the airing of Yoshiyuki Tomino’s Mobile Suit Gundam on Nagoya Broadcasting Network in 1979 fixed the image of the piloted robot in the minds of audiences. Shirow’s work channels both legacies into an era of networks, hackers and heavyhanded policing. His mechanical ‘landmates’ are bulbous exoskeletons employed by construction workers and police officers, key artefacts in his tech-noir plots that just happen to double up as set pieces for gratuitous erotica, as they often open to reveal scantily clad female pilots. His iconic ‘Fuchikomas’ are insectoid single-person tanks employed by law enforcement agencies, semi-independent machines that also co-compile their experiences into a shared intelligence at the close of each working day. It’s testament to Shirow’s multilayered storytelling that a labour dispute of existential enormity occurs between these robots and their masters in the background of Ghost in the Shell, never coming fully into focus but colouring its future world with artificial intelligence’s struggle for sentience and recognition.

You could position Shirow comfortably within a pantheon of graphic sci-fi innovators such as Yukito Kishiro, Hiroya Oku, the all-female collective CLAMP or Katsuhiro Otomo, whose works Battle Angel Alita (1990–95), Gantz (2000–13), X/1999 (1992–2003) and Akira (1982–90) have respectively reprogrammed the language of postwar comics into new expressions of apocalyptic urbanism and cyborgian fusion. But none of those brilliant artists really smashed through the comics control-panel in the way that Shirow occasionally did, allowing his almost maniacal interest in scientific evolution to find disorienting expression in his own graphical rewirings: dialogue that bows under the weight of its own heady speculations, plots that meander through nonsensical labyrinths of technocratic opacity. And it’s these textures of complexity that lent his fictions traction with American audiences throughout the 1990s, cementing their influence within the broader cultures of a cyberpunk that was rapidly encroaching on the turn of a new millennium.

Toren Smith, the American founder of manga import and translation company Studio Proteus (which played a significant role in introducing Shirow’s work to the West), suggested in a 1996 interview with the lauded translator Frederik L. Schodt that Shirow’s demanding dialogue and slower reading pace were preferred by audiences versed in narrative-heavy sci-fi and fantasy comics, and a stark contrast to the text-light character of popular ‘shōnen’ exports aimed at teenage audiences, such as Akira Toriyama’s martial arts fantasy Dragon Ball (1984–95). And it’s easy to see parallels between the lyrical density of Shirow’s works and significant milestones in the development of the cyberpunk genre, from Bruce Sterling’s edited collection Mirrorshades (1986) to Neal Stephenson’s religion-as-computer-virus thriller Snow Crash (1992). The theorist Takayuki Tatsumi has written lucidly on the transcultural exchanges of cyberpunk, especially in light of the Orientalism of William Gibson, Pat Cadigan and others, allowing us to position Shirow’s works not simply as an Asian reflection of the America’s science-fiction exports, but as part of an intricate circuity of Japanese speculative literature and artistic practice that includes the gestational parables of science-fiction writer Mariko Ōhara, the junk installations of artist Seiko Mikami or the cybernetic body horrors of filmmaker Shinya Tsukamoto, a menagerie of ‘semiotic ghosts’ that anticipate cyberpunk’s formalisation into a recognisable style.

There’s still much to be unpacked when it comes to the question of whether or not cyberpunk ever delivered on its implied promise to ward off an accelerationist future beholden to transhumanist intrusions, charismatic techsolutionist oligarchs or the corporate franchising of government. If most cyberpunk treads an ambiguous line between stark warning and terminal celebration, Shirow’s work performs a different calibre of ambivalence. Unlike British comic 2000 AD’s Judge Dredd (1977–), which notoriously satirised police brutality and fascist state-violence throughout the Reagan-Thatcher era and into the present, Shirow’s stories revel in the extremity of police exploitation and extrajudicial murder. A character in the 1999 anime Gundress, for which Shirow provided designs, relishes the opportunity not to read a suspect their rights, while the OVA series Dominion: Tank Police (1988–89) turns instances of police-state terror into unnervingly cute comedic tableaux. When I was last in Tokyo, the company behind the latest adaptation of Ghost in the Shell, Production IG, had licensed its image to the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department for use in an anti-terrorism poster campaign. I joked at the time that this might be an instance of the ‘animatic state apparatus’, but it belies an uneasy proximity between cartoon imagery and statecraft that’s certainly intensifying as Russian private military companies such as the Wagner Group use kawaii anime imagery in their recruitment videos, and Ukrainian soldiers slap chibi stickers onto missiles and munitions before firing them into enemy strongholds. Perhaps one aspect of Shirow’s image world did come to pass.

Shirow is notoriously reclusive and loathe to give interviews; even his name is a misdirection, a pseudonym inspired by the great medieval swordsmith Gorō Nyūdō Masamune. He has deflected public attention since his career in comics appeared seismically to implode following the Great Hanshin Earthquake of 1995, an event that (he claimed) destroyed his work-in-progress on several comics, but that would also see him strangely reinvent himself as the author of a peculiar brand of biomechanical digital smut, otherwise known as ‘hentai’. Many commentators have suggested that this segue into pornography was an attempt to avoid the harsh editorial deadlines that have broken so many manga authors, although Shirow has never clearly explained why he stopped drawing comics. What remains is a strange scenario in which readers might awkwardly celebrate his earlier works, rightly praising its influence in both comics and the broader field of science fiction, while remaining keenly aware of the uncomfortable ‘ick’ his later works carry.

Shirow’s work continues to inspire countless adaptations, and it’s a mild shame that Mamoru Oshii’s poignantly metaphysical animated interpretation of Ghost in the Shell (1995) has received significantly more critical attention than its comics source-material. There’s a distinct tonal contrast between the two, suggesting that the pensive articulations of this admittedly beautiful anime are perhaps worthier objects of regard for any serious philosophical enquiry than Shirow’s frequently crackpot, humorous and boob-laden riffs on the posthuman (Oshii would even cast ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’ author Donna Haraway as a police forensics specialist in the film’s sequel, making its intellectual precedents plain).

But this imbalance does a slight disservice to Shirow’s original vision, which is replete with studied footnotes on the nature of consciousness, the transmigration of intelligence and, perhaps most importantly, the author’s own technical notes on how his own imagined technologies might be engineered. His wild imaginings often veer from the frenzied concept-engineering of new military hardware in the artbook series Intron Depot (1992–2014) to a form of holistic and benevolent worlding in the incomplete and never translated comic-book-cum-engineering-manual Neuro Hard (1992–94) that leaves any true sense of his political orientation surprisingly opaque. These ‘catalogue’ works specifically anticipate a novel turn in contemporary graphic literature, however, where the ‘artbook’ or ‘manual’ provides the template for new forms of storytelling that dispense completely with the sequential, perhaps best recently exemplified by the work of Italian artist Plastiboo, whose book Godhusk – Rebirth (2024) takes the form of an instruction manual for a lost or nonexistent videogame, where any narrative might be vaguely intuited from character designs or item descriptions.

What’s remarkable is the way Shirow’s comics continue to emit feedback signals that complicate contemporary interpretations of his work. When commentators baulked at the casting of Scarlett Johansson as Motoko Kusanagi in the disappointing 2017 live-action version of Ghost in the Shell as an instance of whitewashing, a subsection of fans were quick to point out that Shirow had already anticipated such racial bias in his original comics, portraying the manufacturer of cyborgian bodies, Megatech, as beholden to unrealistic European aesthetics. It’s reassuring then that his pages are currently the focus of a large retrospective at Setagaya Literary Museum, Tokyo, where his technically daunting draughtsmanship will be showcased in a way that will hopefully catalyse new interest in his contributions to science-fiction literature. While the contemporary Shirow remains somehow historically disembodied from his best comics work, his legacy discoloured by the awkward charge of his pornography, those early themes of dislocated consciousness and hypernetworked identity continue to speak to a present caught in tech-solutionist hyperdrive. Plugging into his works today, we can still hear the persistent signal of a distant intelligence whispering coded messages to us through the ether.

The World of Shirow Masamune: Ghost in the Shell and the Path of Creation is on show at the Setagaya Literary Museum, Tokyo, through 17 August

Jamie Sutcliffe is a writer, curator and codirector of Strange Attractor Press

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.