As the artworld descends on Seoul for Frieze and KIAF, our editors pick out the shows they’re looking forward to

Woosung Lee

Hakgojae Gallery, through 13 September

Woosung Lee’s precise, studied paintings feel like a kind of archaeology of the present, portraying cryptic messages from an indecipherable moment. Eternal Story (2023) depicts a set of large smooth stones, all of them engraved with runes in the shape of a laptop, an airplane, a fast-food cup. These are immediately recognisable to us, but what will people thousands of years from now make of such iconography? Other more direct portrait paintings seem to ask a similar question, capturing people in offhand, seemingly blank moments, sitting thinking or just staring at a laptop: Is this what will endure of humans? The I Am Still Working series (2023) features a contemporary version of a cave-painting stick figure, yellowed and bent in weariness, going through the motions: trudging tiredly through the snow, hunched over an empty notebook, slouched on a couch in a karaoke booth, singing mournfully. Chris Fite-Wassilak

off-site

Art Sonje Center, through 8 October

How does spatial environment affect an exhibition? Off-site explores this question by playing with the parameters of what defines a place – ‘pushing the boundaries’, so to speak, between art and its viewing environs. The exhibition takes place throughout Art Sonje Center’s functional spaces, where six artists and artist groups present works that respond to its theatre, backstage area, dressing rooms, garden, stairways, utility rooms and rooftop. GRAYCODE, jiiiiin are an electroacoustic duo known for visualising sound and data in immersive light sculptures; Jong Oh’s delicate geometric spaceframes play with negative space to imply the positive; the pipework lattices of Yona Lee recall the service conduits that make up a building’s bones; Hyun Nahm experiments widely with materials, including recycling failed, abandoned or unexhibited efforts into new sculptures; and Jungyoon Hyen’s visceral sculptures endeavour to put the organic into cartoonish dialogue with the architectural. The tensions between artworks and space have long been explored by artists, but to journey to an institution without entering the actual exhibition space is an interesting turn of events, one that might stretch the possibilities of experience. Marv Recinto

Haegue Yang

Kukje Gallery, through 8 October

Back in 2003, Haegue Yang created Storage Piece, which featured the bits and pieces from various unsold installations packed onto four pallets. (That work, created for pragmatic as much as conceptual reasons, was later sold and unpacked into its constituent parts.) It’s perhaps in the same line of thought that her current show, featuring sculptures created over the past decade or so, in Kukje’s hanok space in Seoul, takes the idea of ‘hibernation’ as an organising theme. According to the artist that means that visitors will encounter the work in a more ‘natural’ state, scattered across the narrow space rather than staged, as is the way of most gallery shows (this, the gallery suggests, will be an ‘offstage’ encounter). Of course, in reality, this is going to be no more or less staged than any other show, but for the collectors among you, perhaps there will be the added thrill of encountering the work in its ‘natural’ environment. And, presumably, bagging one, like some great game-hunter. Nirmala Devi

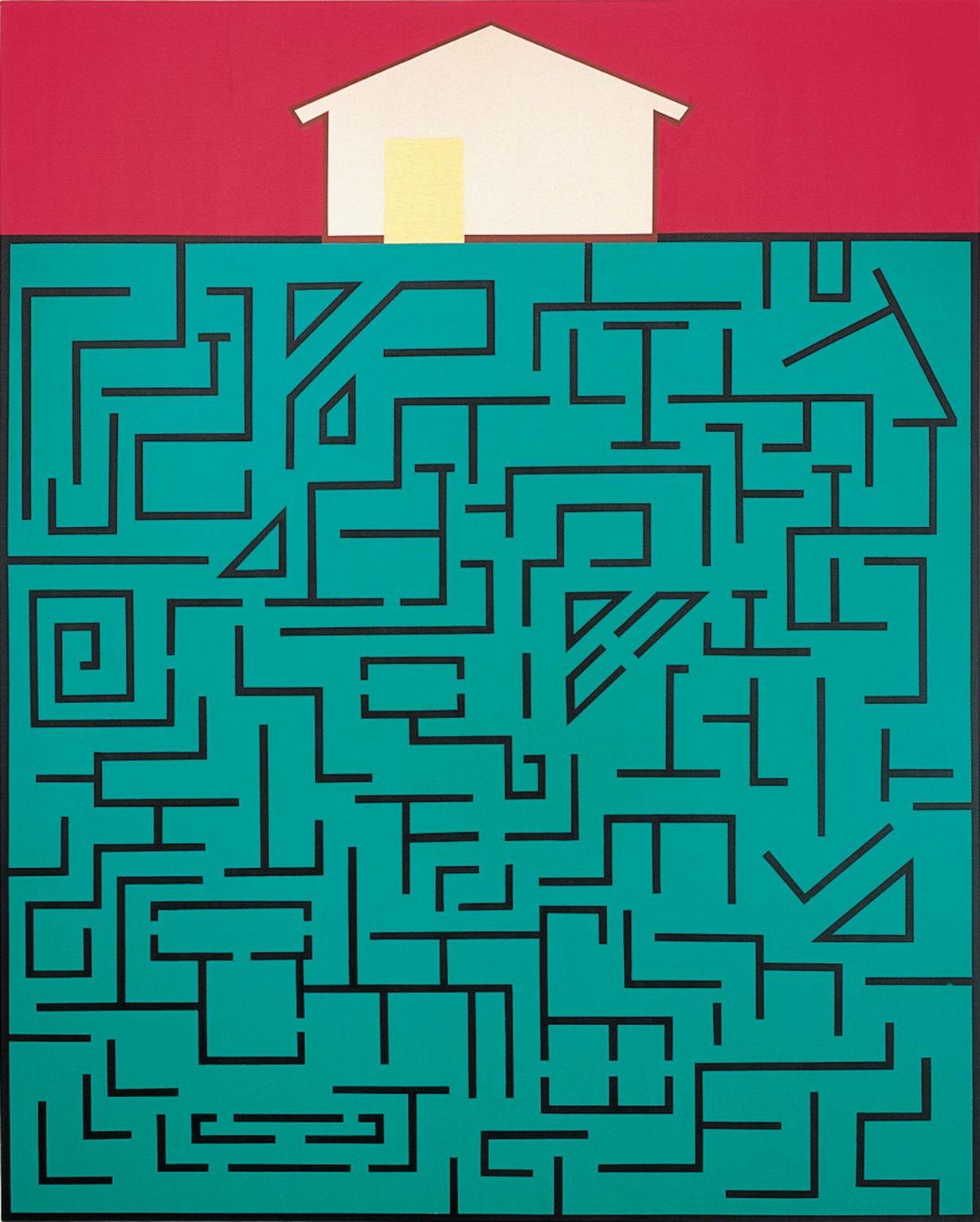

MeeNa Park

One and J. Gallery, through 22 October

Launching their new gallery space in Gangnam district, One and J. Gallery turns to conceptual painter MeeNa Park. While the Maison Hermès in Seoul displays Park’s Nine Colors & Nine Furniture (2023) series – where the outlines of sofas, armchairs and chaise longues are painted at the bottom of large canvases, the rest of which are filled with bright, colourful stripes – this show seems to portray the houses in which such furniture might sit. Drawing on works from the ongoing House series that has run through over Park’s career of the past few decades, these canvases depict a range of iconic and emblematic abodes, such as the puzzle of Maze House (2002), in which an empty white building sits atop a tangled warren of turquoise passages that dominate the rest of the image, or the hut done up in the manner of the blocky street-markings of %j (2008), all of which beg the question, where do you call home? Chris Fite-Wassilak

Koo Jeong A

PKM Gallery, 6 September – 14 October

Koo Jeong A is slated to represent South Korea at next year’s Venice Biennale, but those of you who can’t wait until then might want to trek to Seoul, for her latest gallery exhibition, Levitation, to look for clues as to what she might be up to. There’s pretty much no medium that this citizen of the world (her gallery suggests she lives ‘across the globe’) doesn’t work in, from urban interventions (skateboard parks) to sculpture, so don’t look for clues there (but, spoiler alert, the Venice project looks like it’s taking smells as a theme). Koo’s work, however, does play with perception and the poetics of space, so perhaps do look out for that. And pay attention too, as she can mix the subtle with the obvious, the real with the imaginary, and she has a penchant for things that appear drawn from the everyday. At PKM, it’ll be drawings and digital animations. Venice speculators will need to make of that what they will. Nirmala Devi

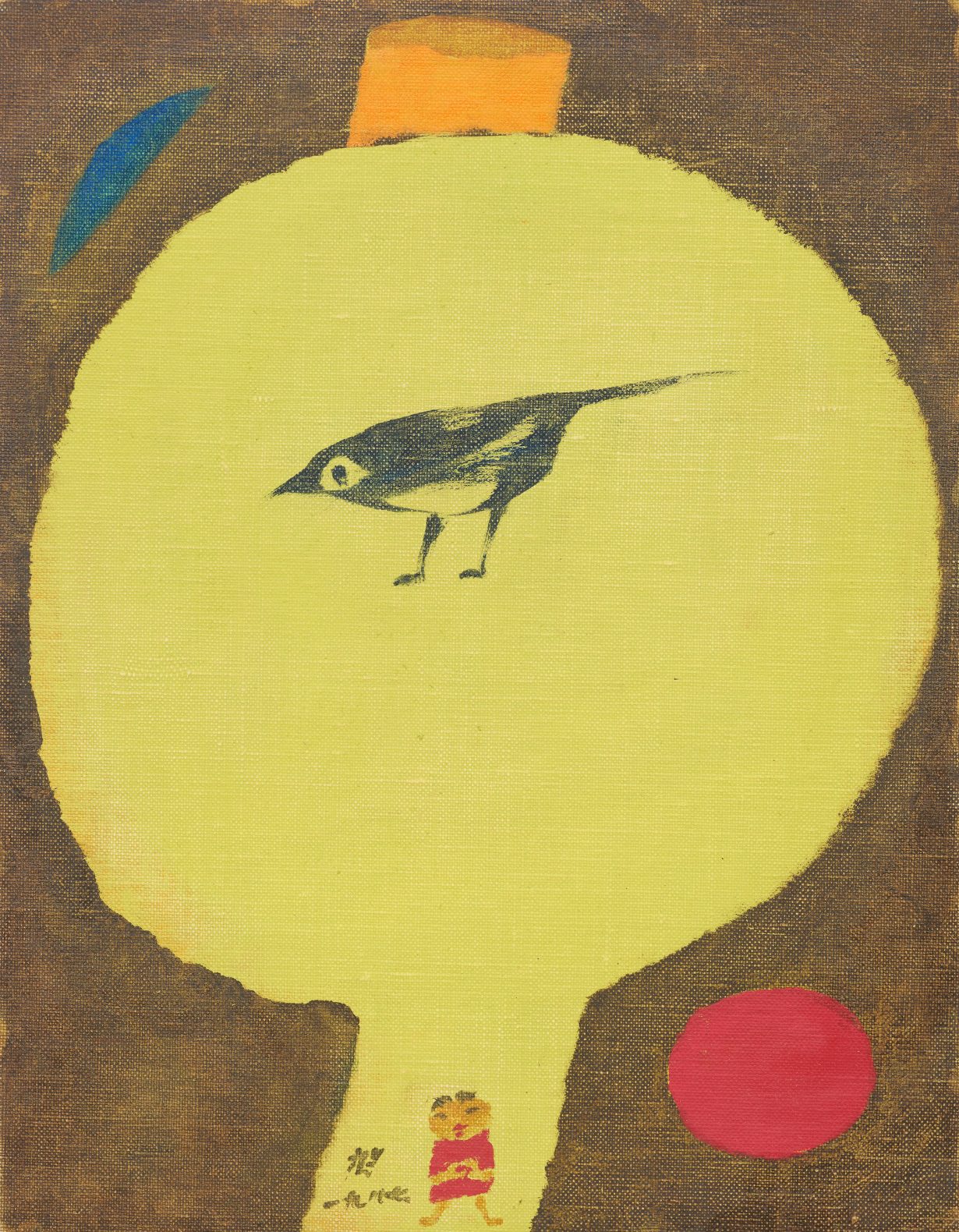

Chang Ucchin

MMCA Deoksugung, 14 September – 12 February

Like most of the generation of artists who came of age under the Japanese occupation of Korea, the late Chang Ucchin (he died in 1990) studied art in Japan (Tokyo) and only learned about traditional Korean art after liberation, in 1945. Like fellow members of the New Realism Group, Chang then set about modernising tradition (which in some respects meant looking both to home and to the West), to no little public acclaim. His work, presented in a retrospective titled The Most Honest Confession, is characterised by its simple geometry and pared-back, childlike simplicity (comparable, in some instances, to the European CoBrA movement), much of it as inspired by Buddhist philosophy as it is by any aesthetic theory. What’s striking about Chang’s work is its playfulness (which also translates into rapid changes in style and form), both when it comes to contrasts of scale and suggestive patterning. And, of course, his focus on nature (particularly birds and trees) is very firmly back in vogue. Nirmala Devi

12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale

Various venues, 23 September – 19 November

In medieval Europe, cartographers depicted other places as lands filled with monsters; more recently, Vietnam banned the Barbie film, which included a glimpse of a world map that indicated China’s territorial claims over the South China Sea. The practice of mapping has always been intertwined in ethnocentric imaginations and political interests. THIS TOO, IS A MAP, as the 12th Seoul Mediacity Biennale is titled, wants to reconceptualise how we think about borders by focusing on social and ecological networks, the nonterritorial and the dispersed. The SeMA Bunker gallery, located underground, will include works by Femke Herregraven and the Lo-Def Film Factory that investigate histories of extraction and pollution of natural resources. Jesse Chun’s solo exhibition at the Seoul Museum of History includes new work that charts the historical, political and spiritual experiences of women in Korea, while the biennale’s four other venues, centred around the Seoul Museum of Art, will present work by artists including Mercedes Azpilicueta, Chan Sook Choi, Torkwase Dyson, ikkibawiKrrr, Natasha Tontey, Jaye Rhee and Bo Wang. Yuwen Jiang

Looking ahead:

Adam Boyd, Chaewon Lee, Rim Park

ThisWeekendRoom, 6 October – 4 November

Is a landscape still a landscape if there isn’t any discernible focus on ‘land’ or ‘scape’? The trio of artists showing work at Seoul’s ThisWeekendRoom will be questioning just that via their ‘reinterpretations’ of the genre. Adam Boyd plays Frankenstein with his collaged wall pieces made up of bits of textile printed with photos of parts of urban structures and abstracted closeups of roughly sewn-together materials. His work isn’t quite as hack-uppy as it sounds, though: in Slipped out of the air (2022), tendrils of sewn lines that follow the crystal-like pattern of a building’s photographed windows extend from the fabric on which the image is printed and onto an adjacent silky silver-grey material. That sense of delicacy also extends to the outer edges, which are left softly frayed. Perhaps more conventionally landscape-like are Chaewon Lee’s paintings, in which the mysterious hulking ice forms that dominate the centre of many of her works give them a surrealist vibe; these indeterminate beings erupt out of starlit snowy dunes, pose in flower meadows or against the backdrop of a mountain range. Out of the three, Rim Park’s style of work requires visitors to expand their notions of what a landscape is, or rather, reduce it to a microscopic level – since that’s what her wallworks made of paper, metal and wood resemble: mutated plant cells, jagged and writhing, the imagined beginnings of a radioactive landscape. Fi Churchman