This year’s shortlist champions art as social activism – but the emphatic endorsement from a mega-institution reveals how thin those radical postures really are

So the Turner Prize’s doleful quest for relevance continues. After a COVID-cancelled 2020 edition (the prize money was redistributed to 10 artists as ‘Turner bursaries’), this year’s prize jury appears to have picked up from where the controversial 2019 edition left off: in that edition, the four nominees, insisting that their values as artists were ‘incompatible with the competition format, whose tendency is to divide and individualise’, declared themselves a ‘collective’, and were jointly awarded the £40,000 gong. And now the prize’s 2021 shortlist has a hot new talking point – all the artists are ‘collectives’.

As Tate Britain’s Alex Farquharson enthused, the Turner Prize ‘captures and reflects the mood of the moment in contemporary British art’. How do collectives reflect this mood? Well, as the Tate’s press release put it, ‘all the nominees work closely and continuously with communities across the breadth of the UK to inspire social change through art’.

Social change through art, and artists working as collectives, have become pet interests for the Turner Prize and for the Tate as an institution, and this year’s collective-fest suggests the prize is doubling down on the virtues of togetherness, anti-individualism and art as social activism. With social-housing-project collective Assemble’s 2015 win, and investigative-journalism group Forensic Architecture’s nomination in 2018, this wall-to-wall attention to collaborative groups is really about signalling a commitment to art as political instrument.

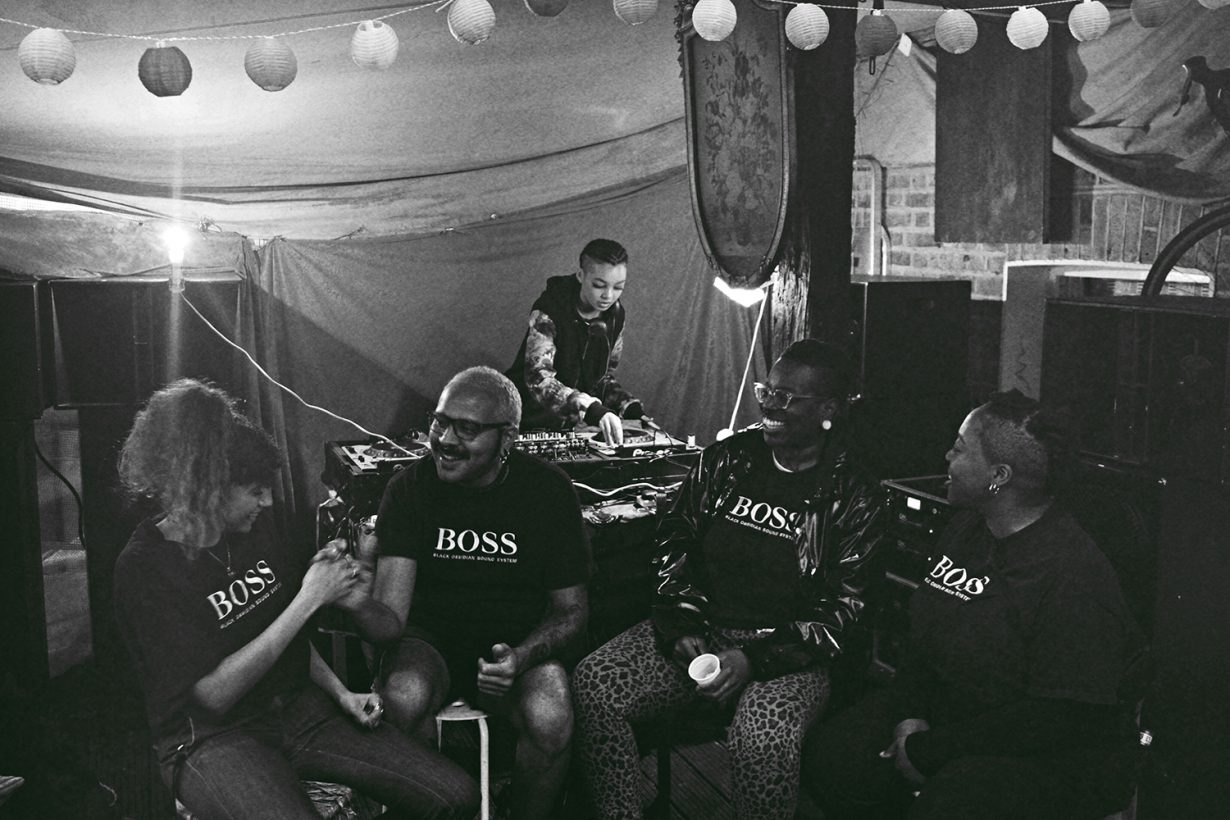

After all, the nominees are brimming with progressively-minded politics: Cooking Sections ‘explore the overlapping boundaries between art, architecture, ecology and geopolitics’; the Cardiff-based Gentle/Radical is run by artists, community workers and others who ‘connect community, politics, spirituality and social justice’; Belfast’s Array make art, street interventions and protests that align with a panoply of social justice issues, from gentrification to abortion rights to LGBTQ issues to the politics of Northern Ireland; Project Art Works are ‘neurodiverse artists and activists’ based in Hastings; and Black Obsidian Sound System is ‘a London-based collective which works across art, sound and radical activism […] formed by and for QTIBPOC (Queer, Trans and Intersex Black and People of Colour)’. The politics of intersectionality and environmentalism loom large.

That the Turner Prize should pivot to radical-sounding collaborative groups says more about the Tate’s desire to endorse what aren’t really particularly radical or oppositional positions, in order to be seen as progressive itself. Collectives may sound grass-rootsy, even politically edgy, but the emphatic endorsement from a mega-institution reveals how thin those radical postures really are. While ‘collective’ retains echoes of the radical political organising of yesteryear, these aren’t dangerous antagonists to the cultural or political establishment, but groups often supported by public funding and private philanthropy, rehearsing the tenets of contemporary ‘woke’ politics.

© Project Art Works

So while the Turner Prize gestures support for purportedly radical artistic practices, its role is really to put a stamp of approval on what certain sections of art’s public-sector establishment wants to promote to the public. The jury’s enthusiasm for art as a social intervention isn’t so much a reflection of the wider state of art in the UK right now, but rather of the fashions prevalent among its institutional curators; with the exception of screen star and art enthusiast Russell Tovey, the judges are directors of Arts Council-funded galleries or private foundations. The connections are always a little incestuous: Zoé Whitley, director of the Chisenhale gallery, was previously a senior Tate curator; Aaron Cezar is director of Delfina Foundation, which has published and supported Cooking Sections, who themselves are currently showing at Tate Britain.

That the Tate’s fawning endorsement reveals something of how orthodox and easy to assimilate these political narratives are has inevitably provoked a backlash – ironically from some of the nominees themselves. Following the shortlist announcement, Black Obsidian Sound System issued a statement levelling criticism at Tate: ‘Although we believe collective organising is at the heart of transformation,’ they declared, ‘it is evident that arts institutions, whilst enamoured by collective and social practices, are not properly equipped or resourced to deal with the realities that shape our lives and work’. The statement goes on to castigate the Tate for a laundry-list of grievances, from its earlier involvement with disgraced art dealer and collector Anthony d’Offay, to its handling of staff redundancies during the pandemic.

But such statements are unconvincing, more a case of posturing to avoid being seen as complicit in the endorsement. Since many artists at the moment see themselves as far more radical than they really are, criticising cultural institutions has become part of the performance of radicalism. The odd thing is how much cultural institutions seem willing to be scolded and told off: rather than part ways with B.O.S.S., the Tate humbly responded by explaining that ‘Tate is committed to championing the work of artists and we always welcome critical dialogue and engagement. Artists must be free to express themselves and share their views however they wish.’

It’s great to hear that Tate is so committed to freedom of expression, of course. The test of such commitment, though, is always how wide a range of artistic and political expressions you’re prepared to tolerate as an institution. In reality, this year’s shortlist narrows that range even further. Once individual artists making art about progressive politics had become ubiquitous, it was only a matter of time before groups making art as if it were progressive politics would be the next big thing.

But the Prize in truth has little to do with reflecting what might be going on in art in the UK, and more to do with an institution wanting to play to the concerns of what it now sees as its core audience of millennials (who anyway never stop whipping it for not living up to their severe ethical and political standards). Rather than try to address the more complex and diverse reality of its wider public, the institution caves in to curators pushing their favoured agendas. That, more than anything, suggests something bigger about the Tate’s current sense of disarray over its role and purpose, since it’s a national institution tasked with representing a national conversation about art – not an activist collective thinking it wants to change the world.