Inspired by David Graeber’s book, The Utopia of Rules at 72-13, Singapore asks how we might hack various systems of control in order to break free

Anyone who has ever dealt with banks, phone companies or government agencies can understand the unique circle of hell that is bureaucracy. According to the late anarchist thinker David Graeber, we now live in an ‘age of total bureaucratisation’, where labyrinthine systems have colonised modern life, stifled our imaginations and paralysed leftist politics, whose leaders cannot imagine a way to upend governments without putting in place another Kafkaesque nightmare. Graeber’s polemical 2015 book, The Utopia of Rules, provides the title for this engaging group exhibition that is loosely about how complex systems of management and hierarchical layers of control structure our daily lives; and how, within these constraints, individuals can nevertheless negotiate pockets of freedom for themselves.

Does bureaucracy have an aesthetic or a feeling? The show provides answers, some more obvious than others. The colour most associated with bureaucracy is grey, of course, as seen in Josh Kline’s installation of cardboard boxes filled with office paraphernalia such as ballpoint pens, tape dispensers, Nescafé sachets, over which grey paint is drizzled (Box S1 – S9, all 2008/25). The installation paints a dreary but unsuprising vision of stale and airless office culture. Meanwhile, a sense of concealment and obfuscation associated with patronage is highlighted in Li Yong Xiang’s Parallel Support & Possess it in a Sleeve

(2023), a folding screen with four painted panels, each depicting the long, flowing sleeves of toga-clad figures. Their identities are ambiguous, because their faces are cropped out of the composition, but by their elaborate dress they appear to be figures of authority (a sense reinforced by the words ‘support’ and ‘possess’ in the title, which evoke a form of control or sponsorshiplike backing). The figures also perform coded hand gestures – pointing fingers, extended palms – that vary in every panel, creating an atmosphere of power and secrecy.

A phenomenology of bureaucracy is suggested in Joaen’s cartoonish batik painting Overwhelmed – coping (2020), which at first glance has little to do with orderly systems. But it captures a feeling of barely contained desperation and anxiety. There is a sort of circuit in the work formed by a naked woman and a long snaking water hose, one end of which is spraying liquid into her mouth. The other end of the hose leads to a funnel, above which the woman is holding a bird in her hand. (The anti-risk adage ‘A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush’ comes to mind.) Outside of this hose-woman-bird circuit, in the background are coffins and a flaming, disembodied head with deranged eyes. Soul-killing and terrible as this system is, it seems it still provides safety and staves off death and madness.

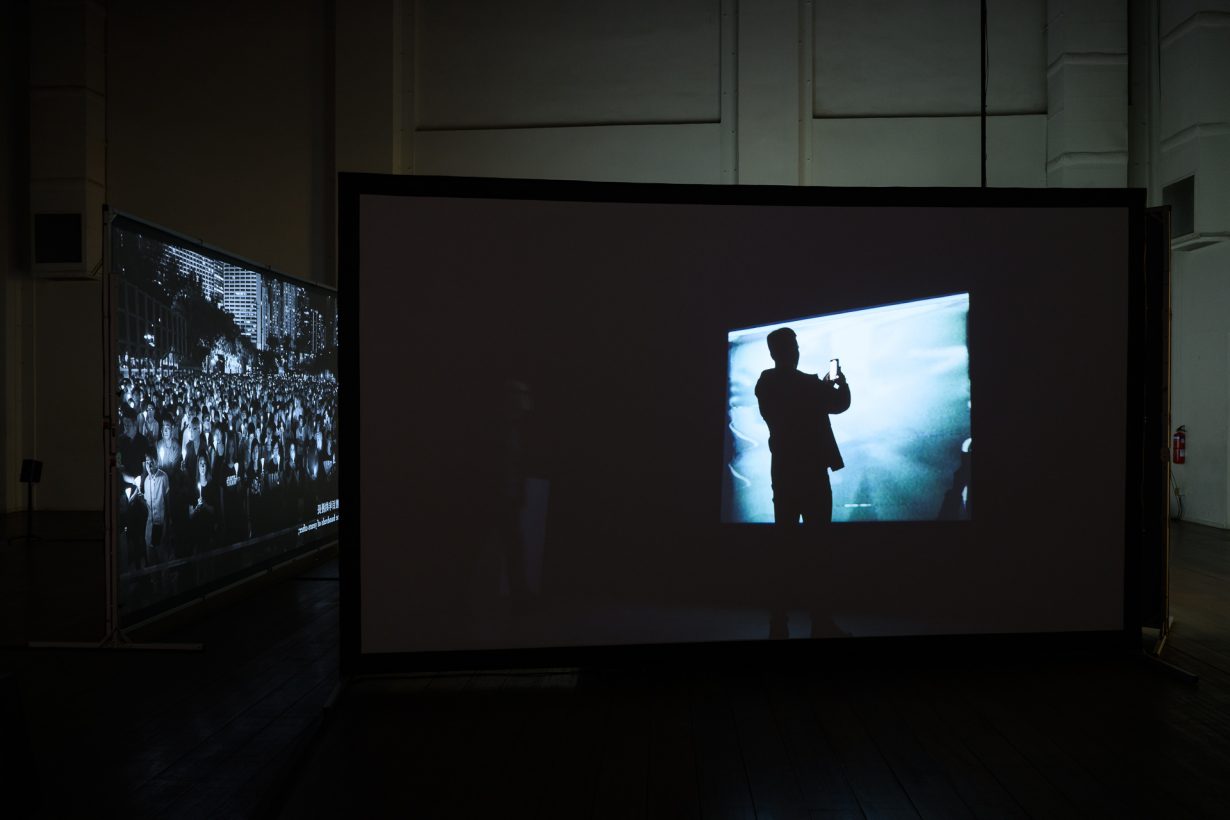

One of the exhibition’s propositions is that art is an exceptional space in which we can escape all-pervasive control from the administrative clutches of some regime, whether neoliberalism, the corporate economy or authoritarian governments (pick your favourite poison). Notably, art is a space for political views that might be dangerous to espouse on other platforms. In Wang Tuo’s three-channel video The Second Interrogation (2023), an artist and a government censor sent to monitor artists conduct a conversation about censorship, the revolutionary potential of art and the role of the artist in an authoritarian state, the artist taking on the role of interrogator. The work, which would have been impossible to show in China, has been shown in Hong Kong and Singapore before this exhibition.

Some artworks appropriate ‘official’ documents to create new and unpredictable affects. Charles Lim’s videowork Alpha 3.9: Silent Clap of the Status Quo (2016) shows edited footage of a deep-sea communications cable laid outside Singapore, in which the camera pans slowly over the seemingly endless structure as it traverses the ocean floor. Filmed by the company that had laid the cable, as evidence of their completed work, the video was obtained by Lim through private connections. What is an impersonal business record is now recontextualised as a strange, chilling document of the invisible infrastructure on which our digital society is built, and the effect of the slow, bland perusal of this thick, secret vein that connects the world is akin to the slow reveal of a monster’s body in a horror flick.

In his book, Graeber outlines the difference between play and games. Games are rule-bound activities that require us to problem-solve; play is ‘open-ended creativity’. He concludes that ‘what ultimately lies behind the appeal of bureaucracy is a fear of play’. But can you play within a bureaucracy? The show celebrates a type of modest freedom that can be found in negotiating rules and regulations innovatively, or by hacking the system. In Tisya Wong’s installation do {} while () (2025), a robot vacuum-cleaner spreads black charcoal dust around a square pen, creating beautiful and hypnotic patterns of swirls and lines. The artist reprogrammed the robot, disabling the hoovering function but not the movement of the revolving side brushes, which create and erase patterns continuously. While this is not exactly spontaneous free play, given the mechanical and banal task that the machine is locked into, it has been allowed to misbehave, so that within the drudgery there is space for beauty.

The Utopia of Rules at 72-13, Singapore, 17–26 January

From the Spring 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.