The year in art – part one: In the cursed year 2025, art staged the increasing centrality of a technological revolution that most people didn’t ask for but can’t escape

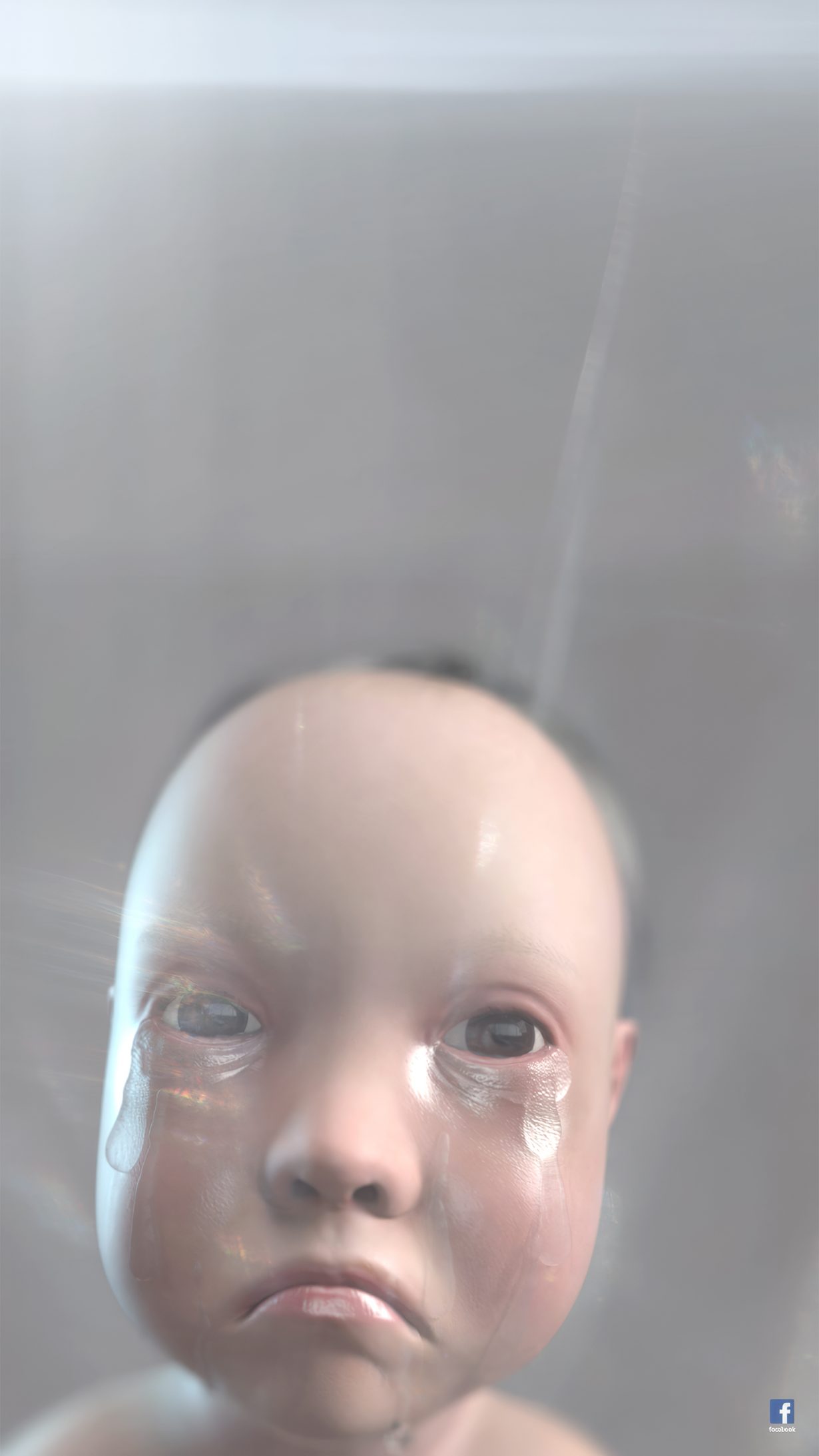

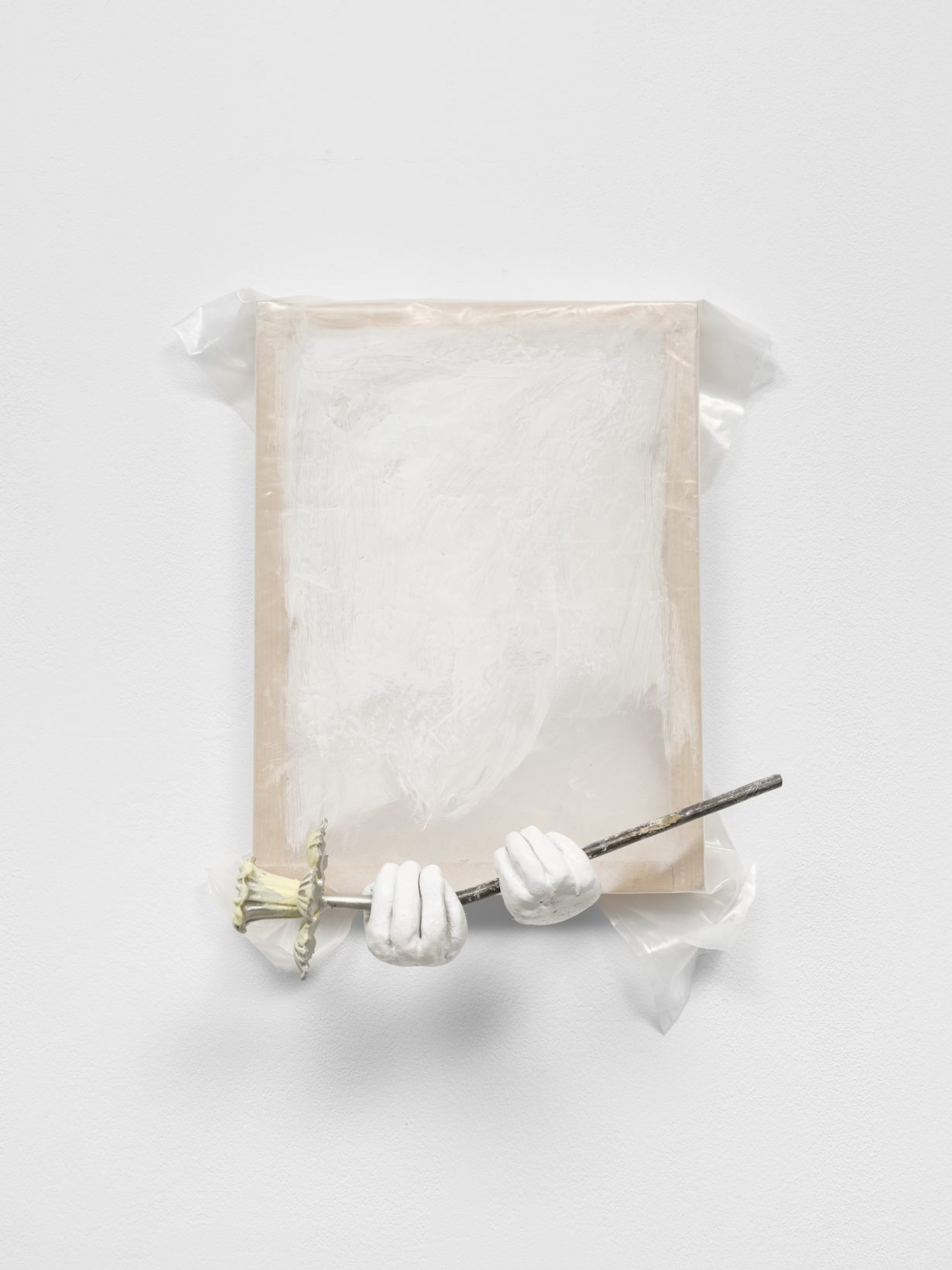

Remember 2021? Pretty bad year! In many ways, though, 2025 makes you nostalgic for it. Case in point: currently, at Isabella Bortolozzi in Berlin, Seth Price is showing works based on generative images of interiors that he made, then archived, during that mid-pandemic timeframe – when generative AI was merely a brand-new, glitchy distraction – and has now lightly humanised using gestural paint strokes. Typically savvy, these tech-driven works avoid short-term obsolescence by consciously leaning into outmoded, slightly spooky aesthetics, characterised by janky hybridised forms. They’re also strongly present-coded, addressing the headlong incursion and increased verisimilitude of AI and how human makers engage with, or against, it. If one was looking, as I am here, for a throughline in the art of 2025, it’d likely be that: the increasing centrality of a technological revolution that most people didn’t ask for but no one can escape.

Artists’ opinions on this subject presently run the gamut from scathing to opportunistic to hopeful. Readers of this magazine’s recent roundtable on ‘post AI-art’ saw creators such as Holly Herndon & Mat Dryhurst – who’ve long treated the technology as a challenge to, and a rerouting of, human creativity – zooming out to glimpse artistry in the shaping of specific platforms for gen AI-assisted art making, rather than in the outputs themselves. Others turn AI on itself. Also currently on show in Berlin, in a solo show at the Palais Populaire, is Charmaine Poh’s video GOOD MORNING YOUNG BODY (2023), for which the Singaporean artist and former child-actress built a deepfake using her many TV appearances, her twelve-year-old self now retrospectively speaking back against her internet trolls. An artist like Philippe Parreno, meanwhile, whose terrific show at Munich’s Haus der Kunst spanned the first half of this year, poeticises ‘loving the alien’ in regard to how generative technologies interact with humans and nature, suggesting hitherto unthought affective possibilities in the process.

At the other end of the spectrum, the rise of prompt-generated, internet-swamping AI slop – accelerated, since spring, by ChatGPT’s new image-generating capacities – has occasioned both incisive opposition (see for example Hito Steyerl’s recent essay collection Medium Hot: Images in the Age of Heat) and the embrace of something like a new, deeply ugly, mindless aesthetic (see Dean Kissick’s semi-sloptimist essay in Spike, ‘The Vulgar Image’). I personally don’t want to engage with something that diminishes my ability to think critically, though hats off if you can thread that needle. And yet, just as a chaotic recombinant internet aesthetic is spreading IRL via objects like Labubus, you can’t escape slop by simply avoiding screens. You can also find non-digital brainrot at art fairs, which – though this year’s Art Basel Miami Beach notably featured a dedicated AI-art section – are still infested with undemanding abstract and figurative painting, as if frozen in a mythical, hazy version of the first half of the twentieth century. Developments here, in an art market that’s wobbled down and up unpredictably this year, are not formal but infrastructural, with bigger galleries chasing inventory and youth appeal by increasingly snapping up the Instagram-friendly emerging artists they’d normally wait for mid-level galleries to hothouse. The big ‘ism’ in contemporary art, in other words, remains good old capitalism.

Recently, interested in seeing something that would take me away from all this, slow everything down and make me think, I went to the Bourse de Commerce in Paris to visit guest-curator Jessica Morgan’s sizeable Minimalism retrospective, Minimal. The astute artist friend I saw it with pointed out that this was an ironically appropriate time to revisit this work, because it was made in a context of war – Vietnam – but generally refused to refer directly to it. (The show, fwiw, is a busy cavalcade arranged in the venue’s circular spaces, with little room to be alone with any work, inviting a viewer to hustle unthinkingly through it, ticking boxes: very 2025.) You could, equally, beam down from space into many galleries and fairs right now and get no sense of our absolutely dystopian and knife-edge era, even though there are so many consequences of a sclerotic capitalist system to be vociferously angry about. The obvious reason for this is that rich collectors don’t want to face the consequences of greed and inequality, and galleries tied to the fair system need such people to keep the lights on.

The contrast is starker when you look at the products of mainstream culture that manage to mirror something of our moment. One thing I intuited repeatedly from some of the past year’s most forceful (and, not coincidentally, celebrated) products in film, TV, music – director Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another, showrunner Vince Gilligan’s anti-AI series Pluribus (thus far), US band Geese’s rock-rebooting album Getting Killed – is a channelled, bare-wires frustration and broad quality of pushback that feels clarifying, productive, near-cathartic. I didn’t see so much of this kind of darkly inventive poetics in contemporary art this year, with the exceptions of Ed Atkins’s Tate Britain retrospective and Jesse Darling’s show at Molitor in Berlin. Maybe, though, I was looking in the wrong places, often at something which seemed to answer the question ‘what did you do in the forever war?’ by saying ‘I made colourful abstract painting’. (There is of course good colourful abstract painting too, and a need for momentary respite; we just don’t need to see it all the time.)

Artists in general are nothing but resourceful and determined, nevertheless, and it’s worth remembering that one way to encourage at least a stubborn minority interest in things made by humans is to multiply the number of crappy things made by nonhumans (that is, if they can find said human-made things). There’s always hope, however embattled. In the first episode of his admittedly anti-counterculture 1969 TV series Civilisation, the art historian Kenneth Clark looks at how art, or at least the visual culture of illuminated manuscripts, survived the Dark Ages; humans managed that, as the segment’s title goes, ‘By the Skin of Our Teeth’. The seeds of artistry a dozen centuries ago, in a context of widespread barbarianism, were nurtured by an archipelago of relatively small communities such as windswept monks marooned on Hebridean islands. If art is to live through its current predicament – pincered between defanging market forces and the encroachments of AI – cross your fingers that we have similar tenacity and similar luck.