The year in videogames: 2023’s best works offered a mix of unfettered escapism and acute anxiety

For the past few years, the world has grappled with successive crises: climate, cost-of-living, a pandemic, large-scale on-the-ground conflicts between sovereign nations. 2022’s word of the year was ‘permacrisis’ which 2023 continued to deliver; writer Kyle Chayka even called for a fresh term that accurately describes this perception of a relentlessly bleak period. He put forward a few terms including ‘The Long 2020s’ and ‘Chaos Interregnum’ but arguably the most incisive was the simplest put: ‘The Time Before Things Got Really Bad’. It tapped into a far more disquieting notion that we’re in fact living through the calm before the storm – that the full terror of our current crises is yet to be unleashed.

Some of 2023’s biggest and most acclaimed videogames, including Baldur’s Gate 3, Starfield and The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, spoke to the current moment by offering sanctuary from it. Baldur’s Gate 3 is a largely faithful, often miraculous virtual reimagining of the Dungeons & Dragons tabletop role-playing game in which you can be, and indeed, have sex with, almost anyone. Starfield offers an entire cosmos to explore. Tears of the Kingdom, meanwhile, adds surprisingly robust building mechanics to one of the most reactive, emotive virtual worlds ever created. What united these formally divergent games was their chasing of the most mercurial of design goals: total freedom.

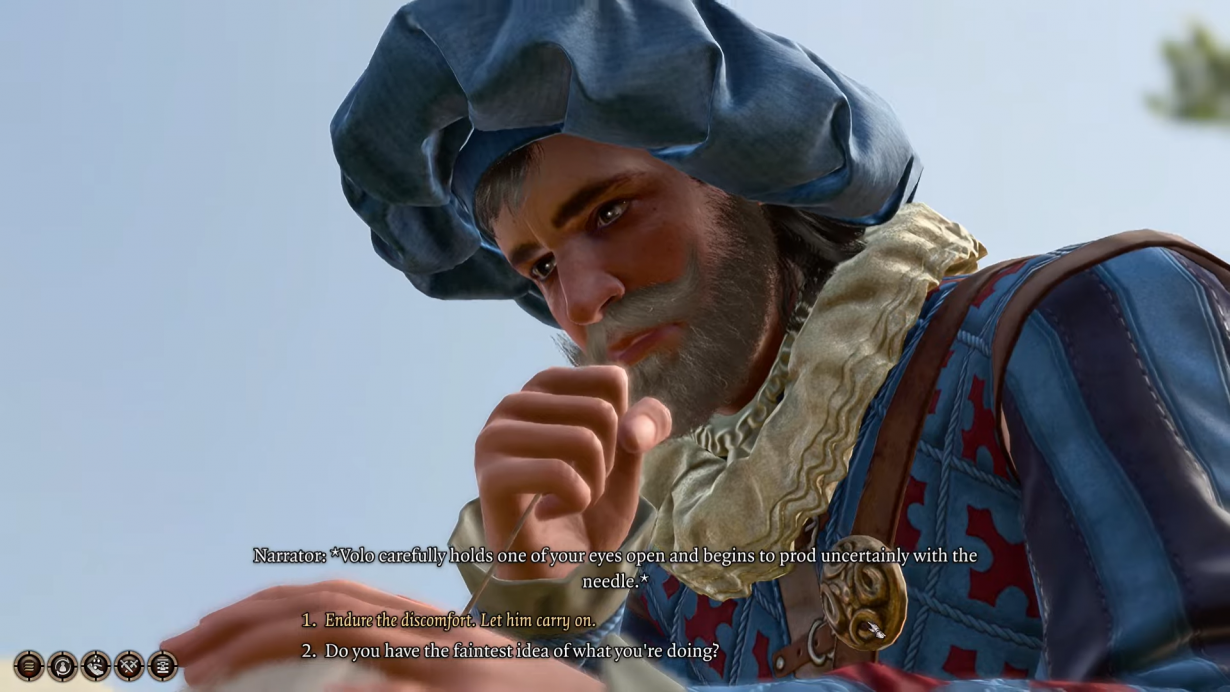

The beauty of Baldur’s Gate 3 is how it conceives of freedom not merely in terms of space but through identity and choice. Its high-fantasy setting offers a plurality of faiths and peoples for you to roleplay as, although the race of mushroom beings called Myconids (who speak together as a ‘harmony of the collective’) is sadly off limits. Even in seemingly sticky situations, the game rewards curiosity, like when I let a wandering minstrel I’d just saved take an ice pick to the eye of one of my characters in order to remove a parasitic tadpole from their brain. As he dug deeper, I revelled in the moment’s sadistic, BDSM-lite fun, all while the minstrel deadpanned, ‘there is some mild trauma’. Few games in recent memory have made saying ‘yes’ so purely pleasurable as Baldur’s Gate 3, delivering gratifying payoffs no matter how silly or stupid the decision.

By comparison, the freedom that Tears of the Kingdom and Stafield offered was more straightforward. Starfield serves up a platter of 1,700 planets created with the help of 2023’s word of the year, ‘AI’. As a promise of infinitude, the game fired the imagination like no other, but in reality, it was the cumbersome apotheosis of a certain strain of ballooning blockbuster design which favours quantity over quality, surface area instead of depth. Tears of the Kingdom, on the other hand, actually deepened the open-world formula laid by its predecessor Breath of the Wild (2017) by extending the game space into bedrock and pristine blue skies. Within the game’s terra firma, you unearth raw materials to create contraptions using the game’s ingenious new construction mechanics. Its freedom is that of pure imagination, inviting players to invent and build as if they were a child sitting amid a gigantic pile of Lego.

But, beneath the PG-rated action fantasy façade, Tears of the Kingdom is a blockbuster of acute unease. A poisonous substance known as ‘gloom’ emits from gigantic fissures; a hurricane ravages Hyrule’s northern provinces while other parts of the kingdom are unusually hot and cold. It’s as if the entire ecosystem has been thrown off kilter by the surfaced, previously long-dormant matter. Thus, Tears of the Kingdom thrums with the anxieties of our own climate crisis and extractive industries while complicating the place of its protagonist, Link, within its world. The fixer of Hyrule, he’s also mining its resources for his own devices, simultaneously at the mercy of complex systems in flux and an agent of change himself.

Tears of the Kingdom was far from the only game that could be considered ‘ecofiction’ in 2023. Season: A Letter to the Future lets players explore a valley in which teeming wildlife and welcoming inhabitants are about to be displaced by a cataclysmic flood caused by the destruction of a dam. Tchia, an open-world game taking cues from the recent Zelda entries, gives players the ability to ‘soul-jump’ between nonhumans (animals and inanimate objects like rocks), thus embedding them within the ecology of the game’s bucolic Pacific island setting. Jusant is a finely poised climbing game that emphasises oneness with its mountain setting while the blockbuster role-playing game Final Fantasy XVI delivers strikingly apocalyptic imagery as its godlike characters battle, in part, over a dwindling crystal resource.

But the strangest of all these ecofiction games was Dave the Diver, whose aqua-loving protagonist is tasked with catching fish for a nearby restaurant and waiting its tables. A game of two seemingly incongruent halves – underwater exploration and business simulation – it coalesces into an irresistible whole: an oftentimes joyful and charming meditation on the altogether dark subject matter of overwork and the sustainable fishing of our oceans.

The wider industry bore witness to its own incongruences, albeit leaving an altogether more bitter taste than the charming Dave the Diver. During a 12-month period of critical and commercial hits, game makers faced the most brutal series of layoffs for a decade. Some 8,000 jobs (and counting) were lost, including over 1,130 at Electronic Arts, 900 at game engine maker Unity, and 830 at Epic Games, the company behind Unreal Engine and Fortnite (2017). The most disheartening of the lot was the 900 jobs that conglomerate Embracer cut following the collapse of a $2 billion deal with Savvy Games, a games company bankrolled by the oil and blood money of the Saudi Arabian government. For all the joy and wonder that games often summon (outlined superbly in Frank Lantz’s book, The Beauty of Games, published this year), the broader political economy was revealed to be an ugly, broken mess. Its fundamental dysfunction was summed up no more fittingly than the news of Embracer’s share price recently jumping 11 percent – in the eyes of the market, the human cost of such profit-squeezing was worth it.

Amid this inarguably tumultuous time, two games arrived which offered distorted reflections of it rather than any kind of refuge. In metamodernist survival horror, Alan Wake 2, a writer finds themselves languishing in a dream-logic version of New York. It becomes clear that this place is a labyrinth composed of scenes from his own novels: in essence, the writer is trapped in a fiction of his own making. In the surreal puzzle-platformer, Humanity, a luminous Shiba Inu dog leads a bustling mass of people across an obstacle course of brutalist architecture suspended in the sky. As you tinker with their direction of travel, occasionally directing them into a fathomless abyss, the game leaves ample room for you to mull over its charged, metaphorical images. The central question posed by Humanity is one that arguably applies to the year as a whole: How did these people lose their sense of direction?

Alan Wake 2 and Humanity thrum with their own contradictions: absurd, fun, grim, kitsch, profound, silly – works acutely suited to the current chaotic moment by virtue of the extent to which they embrace dissonance. Neither offers a solution per se; instead they let us get lost in the maze of rules and narratives they present. As things, well, Kept Getting Bad, playing both Alan Wake 2 and Humanity felt like a microcosm of videogames in 2023 – a kind of limbo before the real-world unleashes the full force of whatever comes to be its main event.