Zedani’s works eschew the palette and timbre of Gulf Futurism to instead consider the future of the Gulf

Giant prehistoric fungi, biofilms and resurrection plants meet the Chthulucene in Ayman Zedani’s practice. The Saudi artist creates videos, installations and immersive environments that feel like Petri dishes in which to observe human–nonhuman symbiosis. He likes to leave his narratives, which largely arrive from speculative futures or squelchy, viscous pasts, malleable and semiotically open. There’s more than a touch of sci-fi about them, but gentle optimism and an ecological emphasis pitches them closer to solarpunk. Crucially, his works eschew the palette and timbre of Gulf Futurism to instead consider the future of the Gulf.

Growing up between the southern cities of Khamis Mushait and Abha, Zedani would spend weekends camping with his family among the dense juniper groves of nearby mountain villages. Upon moving to Riyadh, he had to renegotiate his relationship to nature. “Nature here is quite different. It took me a while to understand the desert and appreciate it for what it really is,” he says over Zoom, pointing to how the landscape is readily legible to many as a Dune-like ersatz Mars. Zedani studied biomedical science in Australia, taking art classes on the side, and worked as a hospital pharmacist for a while. He began exhibiting his work in 2013, but waited until 2019 to mount his first solo, at Jeddah’s Athr Gallery. It was curated by Murtaza Vali and titled bahar-bashar-shajar-hajar, or sea-human-tree-stone. We can understand it as a kind of hydrous classification, moving from the sea, which has a lot of water, to the stone, which has very little. (One recalls the 1988 Star Trek: The Next Generation episode ‘Home Soil’, in which a sentient crystal barks dismissively at the crew, “Ugly. Ugly. Giant. Bags of mostly water.”) But it also describes Zedani’s arc of inquiry over the past eight years.

Earlier works have an austere, almost sacral quality to them, with stone, clay, charcoal and concrete arrayed into neat grids. Some are site-specific, like Bāb (2018), which embedded 54 concrete cubes in Jeddah’s old city. At Ithra in Dhahran meanwhile is the permanent installation Mēm (2018), for which he won the inaugural Ithra Art Prize in the same year. Its monumental columns – some 2.5m tall and around 400kg each – tower like obelisks uncovered from a distant past, or perhaps an absent future. Like many of Zedani’s works, they have a sense of bypassing the present to stand out of time. Others have an observational quality, such as Azal (2017), which features dyed liquid poured into 20 earthenware cups. Time becomes physicalised as the liquid slowly spreads through the clay, terracotta bruising black like a subterranean petroleum seep.

Work titles from this period spatialise the Abjad system, which assigns numerical values to each letter of the Arabic alphabet. Mēm is the Arabic letter ‘m’, while Thalaatha (2017), which draws from the tenth-century Persian calligrapher Ibn Muqla’s ‘khatt al-mansub’ system for proportioned script, refers to the number three, the wearable charcoal pieces of Arba’a (2017) to ‘four’ and so on. All evince an interest in the interactions and relationships between humans and inanimate objects. Also important is polytheism in pre-Islamic Arabia, where a rock, bush or animal was believed to contain a spirit and accordingly respected. Humans were considered to be part of nature and not superior to it. Later, Zedani would parse these animist beliefs through the new materialist philosophies of Jane Bennett, Anna Tsing’s fungal assemblages and Donna Haraway’s notion of making kin, which would result in a new chapter – as he terms it – of his practice.

Around this time, the artist was invited to an exhibition at the Sharjah Art Foundation. He had actually been working there as a curatorial coordinator for a few years, albeit under a different name. “I don’t think they knew I was the same guy when they approached me,” he says. “I need to separate those two things.” Exhausted from the Mēm project, he returned to the scoby-like biofilms he had been experimenting with for a while but never exhibited, given the pressures to produce at scale. He infused them with herbs and spices from the market next to his studio to create beautiful translucent ‘skins’ of the region. Afterwards, he buried the biofilms in the courtyard outside – “I want to create something that just lives and dies through the exhibition” – a gesture he would subsequently repeat.

Stone gave way to trees, plants, bacteria and other living matter. The artist became obsessed with the construction and consumption of nature in the Gulf: the plasticised palms, the Potemkin hoardings that give the illusion of a hedge, the yeehaw hyperreality of an artificial ski slope or a now-cancelled rainforest under a dome in a luxury real-estate development. Between Muddles and Tangles (2019) documents one such environment, a small island in a Sharjah lagoon that gets wildly, colourfully illuminated at night. The indigenous and imported coexist here: native plants share space with transplanted ones from several elsewheres, and flora and fauna alike have adapted to the uniquely lit new ecology. The video is set to atmospheric music meshed with ambient nature sounds (Zedani composes all the music for his works), to soothing effect. At the NYUAD Art Gallery it was installed alongside fuchsia grow lights and a shelf of Kaff Maryams, a plant that survives arid climes by curling up into a gnarly, rather Lovecraftian ball. When it rains, it unfurls itself and sends out little shoots and white flowers; in folk medicine the tea is used to induce labour and aid in reproductive health. In a 2019 artist book, Sha’ba’kah, made with curator and writer Wided Khadraoui, it is proposed as a regional answer to Ursula K. Le Guin’s carrier-bag theory of fiction; this idea of indigenous plants-as-containers is one that pervades Zedani’s practice.

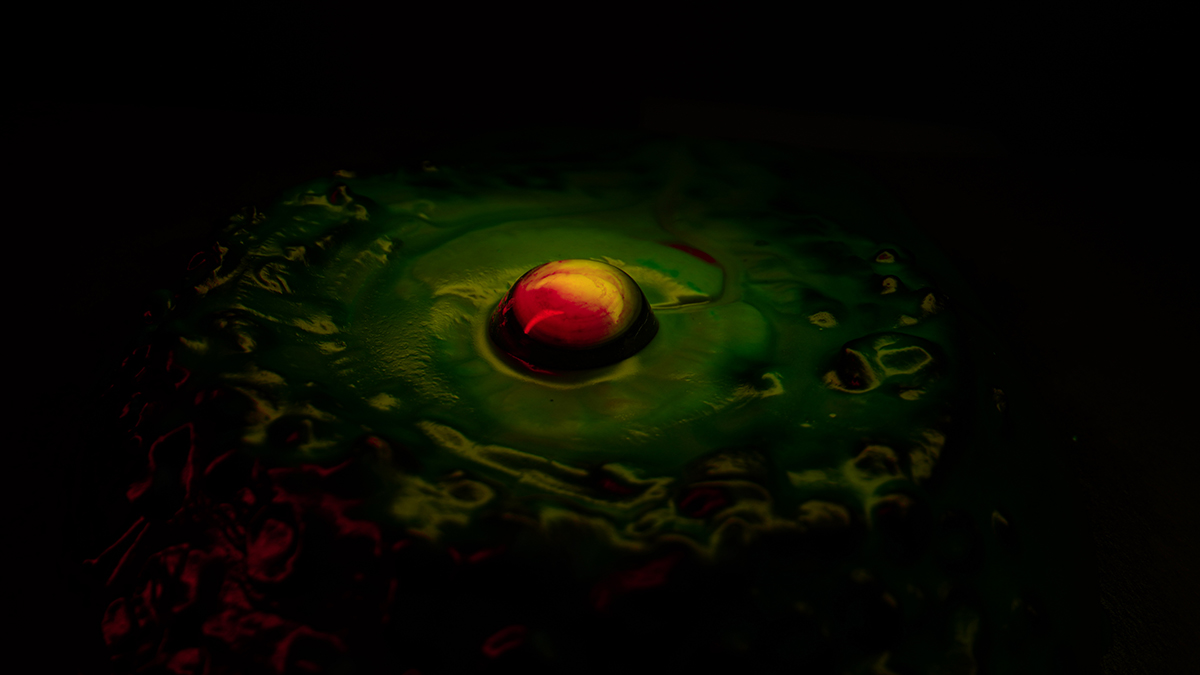

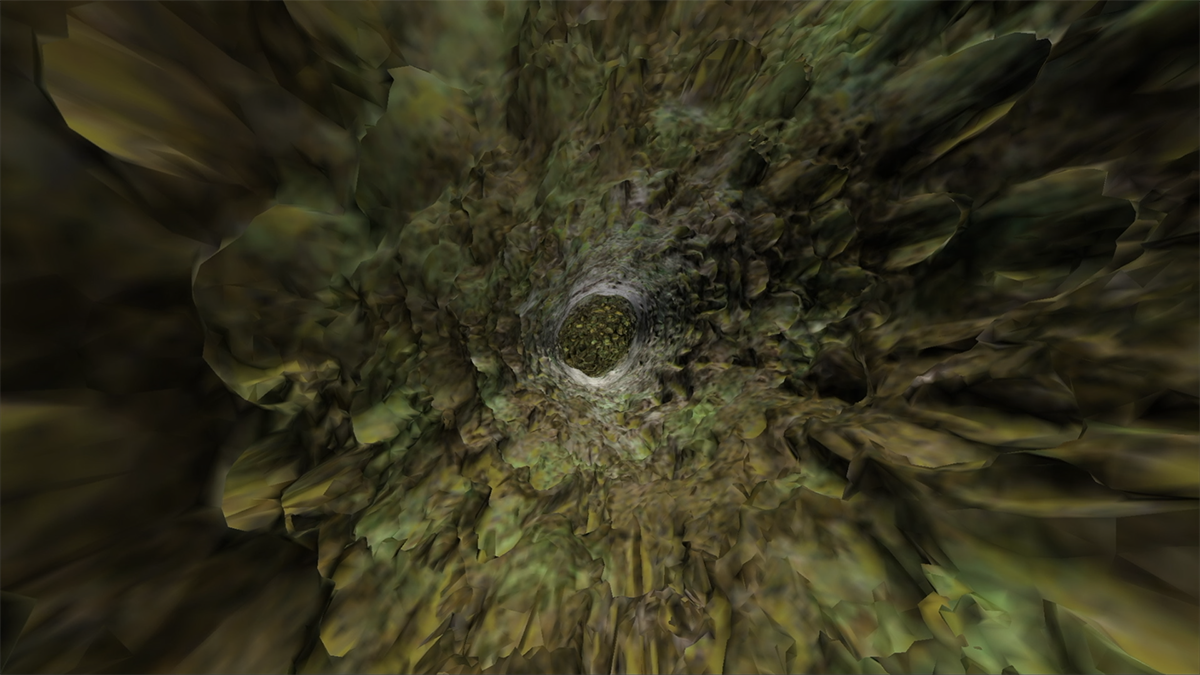

Sometimes, the plants are no more. Among Zedani’s most exciting works is the return of the old ones (2020), a petromaterialist liturgy developed in collaboration with writer Saira Ansari. It is told from the perspective of a Prototaxite, a fungus that lived some 400 million years ago, and voiced in the plummy tones of a nature documentary.

The fungus charts its life, death and eventual transmuted resurrection as the petroleum that became so crucial here: “It’s the souls of all the things that lived on in the Arabian Peninsula a long time ago. And it’s being awakened from its long peaceful sleep in a sense – that changes the way we perceive oil,” Zedani says, framing it as a kind of extended animism. “How would you deal with [things] if you think of oil as the remnant of your ancestors and everything they lived on for a very long time?” (I ask whether he would rather be a plant, or fungus, or oil; he chooses the last, soil.) Later, I notice his email signature, which reads, to my ancestors, human and not human.

Of course, Zedani is not the only one interested in this kind of cultural genealogy. Recent years have seen a concerted push to excavate the region’s pre-Islamic heritage, particularly in Saudi, which hosts some astonishingly preserved (thanks to desertification) sites from ancient civilisations. He gets especially animated about recent discoveries – and how they might upend our comprehension of the past – and tells me about driving past a billboard with Aramaic writing, which he couldn’t read, but which many people are now studying. For the 2020 Lahore Biennale, Zedani would turn his biofilms into what he’d tout as seventh- century pre-Islamic masks in collaboration with writer and geographer Ahmad Makia. “I like when things kind of get blurry, like in terms of fictional or actual,” he notes. Future projects include a look at “gut brains” – which have as many neurons as a cat’s brain – and finally, the sea: he hopes to go to Oman to work with the Arabian humpback whale. “I don’t know what it’s going to look like,” he says with a laugh, “but I’m kind of excited to get to meet them, and say hello. To start something together.”

From the Summer 2021 issue of ArtReview Asia