The example of the Black Panther Party reminds us that a liberated society requires a liberated visual imagination

Eric Jorgenson, a tech entrepreneur and writer whose next book project will ‘collect and curate Elon’s wisdom’, recently assigned his X followers a challenge: ‘It’s a huge miss that Communism has the Hammer & Sickle (which actually goes hard) and Capitalism has nothing. Let’s do better branding for Capitalism!’ The replies were unintentionally tragicomic: bar charts, an ‘anvil of self-determination’, a giant bitcoin blasting off into space. But the exercise laid bare a truth: endless accumulation sustained through force within a finite system is, unsurprisingly, bereft of an emotionally resonant visual tradition.

The latter is no small thing. Political consciousness is partly formed in the symbolic realm. Aesthetics and poetics (sorry, ‘branding’) paint a picture of the values and goals that define a political vision. An ideology unable to nourish people’s imaginations indicates something deeper about the hollowness of its promises: now that we are centuries into capitalism, why indeed has nothing in the way of a galvanising symbol emerged? For the Martinican poet and philosopher Aimé Césaire, the artist – while no ‘Messiah’ – can nevertheless ‘hasten the ripening of popular consciousness’. In his context, popular consciousness meant a people awakened to and united against the sources of their oppression. Whether or not we align with Césaire’s politics, the role of aesthetics and poetics within this belief system is clear. Revolutionary movements understood that image, gesture and style don’t just communicate a mission; they actively contribute to sustaining inspiration over what can be decades of struggle. Black Panthers & Revolution: Stephen Shames, recently on view at London’s Amar Gallery, showcased a visual archive that demonstrates this with piercing clarity.

The Black Panther Party was a revolutionary socialist organisation founded in 1966 in Oakland, California, to advocate for African-American rights, self-defence and social justice in response to racial violence and poverty. While studying at UC Berkeley, Shames befriended Panther cofounder Bobby Seale; he photographed the movement from 1967 to 1973, capturing many now iconic images. These not only include striking portraits of members such as Huey Newton, Assata Shakur and Angela Davis in action, but also the BPP’s everyday, grassroots work: school breakfasts, health clinics and educational programmes.

The BPP understood that Black people also needed another kind of nourishment: dignity. And so, against the caricatured images of Black people in American popular culture at the time – often as happy domestic servants pictured on waffle-mix packaging – they pursued a radical aesthetics. Black leather jackets, natural afros, open-carry firearms; disciplined rows at Panther rallies that visually evoked militancy. Smart young men sporting black berets; women in black turtlenecks with the writings of Che Guevara or Malcolm X to hand. The overall stylistic effect projected a community that was organised, empowered, well-read and service-oriented. It was a total rejection of the three dominant images America had imposed on Black people: infantilised mascot, libidinal criminal or aspirant to middle-class whiteness.

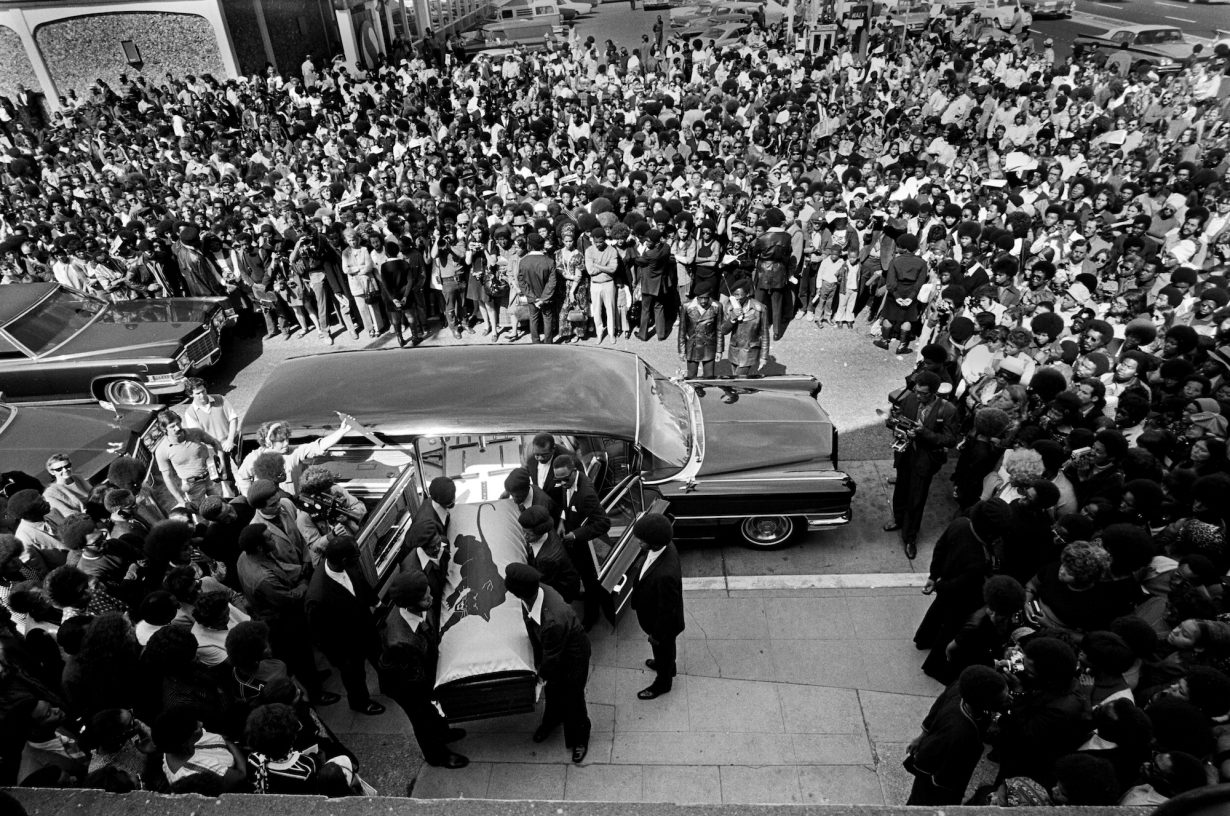

This visual vocabulary was also a rebuke to the respectability politics urged by some. Making their struggle more palatable to advocates of nonviolence had not stopped Black death – Martin Luther King Jr, despite championing peaceful protest, had been assassinated in 1968. The BPP’s aesthetics instead countered the idea of defencelessness. Shames’s untitled 1971 bird’s-eye shot captioned ‘Oakland, California, USA: Black Panthers carry George Jackson’s coffin into St. Augustine’s Church for his funeral service as a huge crowd watches’ shows not pearl necklaces or Sunday hats, but a military-style funeral. With the coffin draped in a Panther flag, guarded by armed members of the party, its visual tone distinguishes death in police custody from a natural death. The omnipresence of weapons serves to remind us that Jackson’s murder was political martyrdom: a war waged against a community.

But this aesthetic was not just masculine, militant posturing. Women made up two-thirds of party membership and led much of its community programming. Though the party as a whole espoused a pedagogical approach to revolution – one where feeding a child was as radical as confronting a cop – tasks were largely gender neutral. For every one of Shames’s images of gun-wielding Panthers, there are several featuring party members, men and women, working for their local community: from distributing food, to conducting health checks.

Stirring iconography as a helpful companion to these practical aspects of community empowerment was widely understood in revolutionary cultures. Even under conditions of armed struggle during the late 1960s and early 70s, the Palestine Film Unit kept making features. Also founded in 1966, the Organization of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America (OSPAAAL) launched bold poster-art with multilingual captions that connected anti-imperialist struggles, situating the African-American struggle within a global fight against oppression. These works often echoed Panther iconography, including the raised fist as a symbol of political resistance.

A liberated society requires a liberated visual imagination. The BPP’s aesthetics – and those of their international counterparts – still hold power because they operate from the understanding that you cannot reshape the world unless you first empower the disempowered. If that means that capitalists too are free to try and find a symbol that gets us psyched up for maximising shareholder value, fair enough. I’ll wait.

Sarah Jilani is a lecturer in postcolonial literatures and world film at City, University of London

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.