In borrowing, mixing and adapting postmodern dance traditions, runway modelling, voguing, butoh and fairground ‘hoochie-coochie’ shows, Harrell reclaims dance as a heritage for all

They came from all over like pilgrims to worship at the altar of postmodern dance. Judson Memorial Church was a Baptist ministry catering to a cross-section of New York’s social classes when it opened in 1891, but by the 1960s it had become the stage for a much more exclusive congregation of avant-garde performance artists, including Trisha Brown, Steve Paxton and Yvonne Rainer. At the turn of the millennium, when Trajal Harrell first attended performances there, the legacy of the ‘Judson School’ had attained the orthodox status of a religion. Brown, the only member of the group to establish her own company, trained countless young dancers there in her late style of the 1980s, which emphasised formal and athletic mastery – a far cry from the asceticism of Judson’s experimental 1960s, centred on restrained, pedestrian movements. Harrell was shocked to find the scene so retrograde. The centre for cutting-edge dance in one of the world’s performance capitals seemed nostalgic for its least radical era.

A smalltown-Georgia native and recent graduate of performance programmes in Providence, Harrell had an insatiable hunger for dance. When he wasn’t attending performances at Judson, he travelled uptown to the Black and Latinx vogue balls of Harlem. During Fashion Week he marvelled at models on the runway, whose restrained poses had informed the gestures of voguing. “Here it is: this is postmodernism,” he tells me he recalled thinking. And so one night in 1999 he mounted the stage at Judson, set down a cd player and began posing, slowly and methodically, to the 1982 Yazoo track Ode to Boy. It was a repudiation of Judson’s then-popular athletic style. “I thought this was a ‘fuck you’ piece,” Harrell says, but when he finished the performance, the church erupted in thunderous applause. Stunned, Harrell left without speaking to anyone, but he knew he had done something important.

That first work, It is Thus From a Strange New Perspective That We Look Back on the Modernist Origins and Watch it Splintering Into Endless Replication, took its name from the last line of the title essay in Rosalind Krauss’s seminal book, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (1985). Harrell’s quotation of a key text celebrating the ‘death of the author’ suggested that dance could only avoid becoming derivative by responding critically to its own past. This was an operation he compares to ‘realness’, the plausibility of a pose or a look in the vogue ballrooms. “I felt that realness brought a critical lens on the idea of authenticity in postmodernism, because there was this notion that there could be an authentic body or a neutral body,” Harrell remembers, referring to the mostly white composition of the Judson scene. The avant-garde movement had been historicised as making dance broadly accessible – centred on everyday, pedestrian movements – when its living legacy had excluded those who, like him, came from different racial or professional backgrounds. By deploying realness, a concept originating in queer communities of colour, he sought to remind his fellow dancers that authenticity is only ever a performance, the success of which is contingent on perceptions of race, gender, sexuality and class that too often go unacknowledged. He was asking who gets to own the history of dance.

That question percolated in Harrell’s mind as he staged more performances around New York, slowly shoring up an iconoclastic reputation. In 2009 it took centre stage in the first of a cycle of works that would occupy him for the next five years. Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at The Judson Church (S) imagined what would happen if vogue ballroom dancers gate-crashed the arch-serious Judson scene, demanding their rightful place in the art-historical canon. In a succession of costume changes to an eclectic pop soundtrack, Harrell pranced down and around a paper catwalk, his limbs too rigidly locked to properly resemble Brown’s late work but his movements too balletic to be considered voguing. In 2012, for Judson Church is Ringing in Harlem / Twenty Looks or Paris is Burning at The Judson Church (Made-to-Measure), Harrell flipped the script, imagining what might have happened if Brown and Rainer had hopped on the A Train uptown to attend a ball, travelling from one deconsecrated ‘church’ to another. Three male performers in loose black robes began tracing sombre, minimal gestures that, by the work’s mid-point, broke out in a frenzied freestyle, as they pranced in circles, swinging their arms wildly, taking turns breakdancing and voguing.

Harrell had not yet concluded his ‘Judson’ series when, in 2012, he first visited Tokyo to study butoh. He had long been fascinated with the highly stylised dance, which developed in the ruins of post-Hiroshima Japan. Its founders, Kazuo Ohno and Tatsumi Hijikata, stripped the ancient Kabuki theatre back to its basics, portraying social outcasts instead of courtly samurais and princesses. “Hijikata was interested in weakness and vulnerability, and giving representation to people whom society didn’t want to look at,” Harrell says. He wondered if, instead of training for decades to become a professional butoh dancer, he could treat the form almost like a voguing category and see how close his imitation could get to the real thing. For his performance The Return of La Argentina (2015) – one of several works that have reinterpreted the legacy of butoh – Harrell riffed on an iconic collaboration between Hijikata and Ohno, Admiring La Argentina (1977; La Argentina being a celebrated Spanish dancer who had died in 1936), that involved a lacey ‘tango visite’ dress and a pipe-organ score. Harrell sashayed into the lobby of Vienna’s Leopold Museum tenderly clutching a gown to his chest to the eight-bit sound of an Atari game.

Such works unlatch questions of cultural appropriation by aiming for something apart from, or beyond, the impression of authenticity. Swapping contexts and genres throws into relief any assumptions about who has the right to engage specific cultural forms. Harrell’s riffs on butoh are specific to his embodied experience as a queer Black man from the American South, opening histories of dance up to new experimentation and play.

This isn’t a particularly novel approach to contemporary art, but in the dance world, where performers train to master a specific style, it has a profound implication: Harrell’s work reclaims dance as a shared heritage from whose categories anyone, regardless of skill, can freely borrow. In the words of queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz, he is a ‘disidentificatory subject… who tactically and simultaneously works on, with, and against a cultural form’.

For the 2016 work Caen Amour, Harrell reversed his eastward gaze to consider an Orientalist spectacle of late-nineteenth-century America known as the ‘hoochie coochie’ show. Performed by scantily clad women at travelling circuses, most notably the pioneering American dancer Loie Fuller, it often involved folding fans and other vaguely Asian signifiers, with angular, stylised movements that recall early modernist dance, albeit decades before the ascendance of Martha Graham. “I’m looking at butoh through the theoretical lens of voguing and looking at early modern dance through the theoretical lens of butoh,” says Harrell. He recalls seeing the hoochie coochie tent at the state fair in his hometown of Douglas, Georgia, when he was a boy, though his father forbade him to enter. Caen Amour imagines what he could not witness, staging a hoochie coochie show in the round so that spectators can see dancers – both male and female – change costumes behind a painted screen. This scenographic gesture collapses public and private, backstage and front, in the same way that Harrell’s work scrambles signifiers of East and West, high and low culture. Such reversals are essential to the way Harrell unlocks forms not only for himself, but for everyone who desires to move in new or different ways.

Harrell has since become a fixture of the international biennial circuit, owing perhaps to his work’s ability to traverse great temporal and geographic distances while requiring little formal training to perform. In 2018 the German magazine Tanz awarded Harrell the title ‘Dancer of the Year’. “It was very shocking to me because I always considered myself to be a choreographer who was a bad dancer,” he recalls. In response, he choreographed Dancer of the Year (2019), a three-part solo performance that incorporated gestures from butoh, vogue ballroom and the streets and Baptist churches of Douglas. In one act, Harrell outstretched a single arm as if shooting a basketball layup, and then two, in a slow yet rapturous hallelujah. These pedestrian movements from Harrell’s upbringing are as constitutive of his understanding of dance as any academic tradition he’s studied. By isolating and extending them, he makes postmodern dance accessible to those who, like him, have long felt excluded by its institutionalisation. “I hoped I could show that anyone could be Dancer of the Year,” he says. The work channelled his belief that dance might live up to its democratic promise. Its congregation should be open to all.

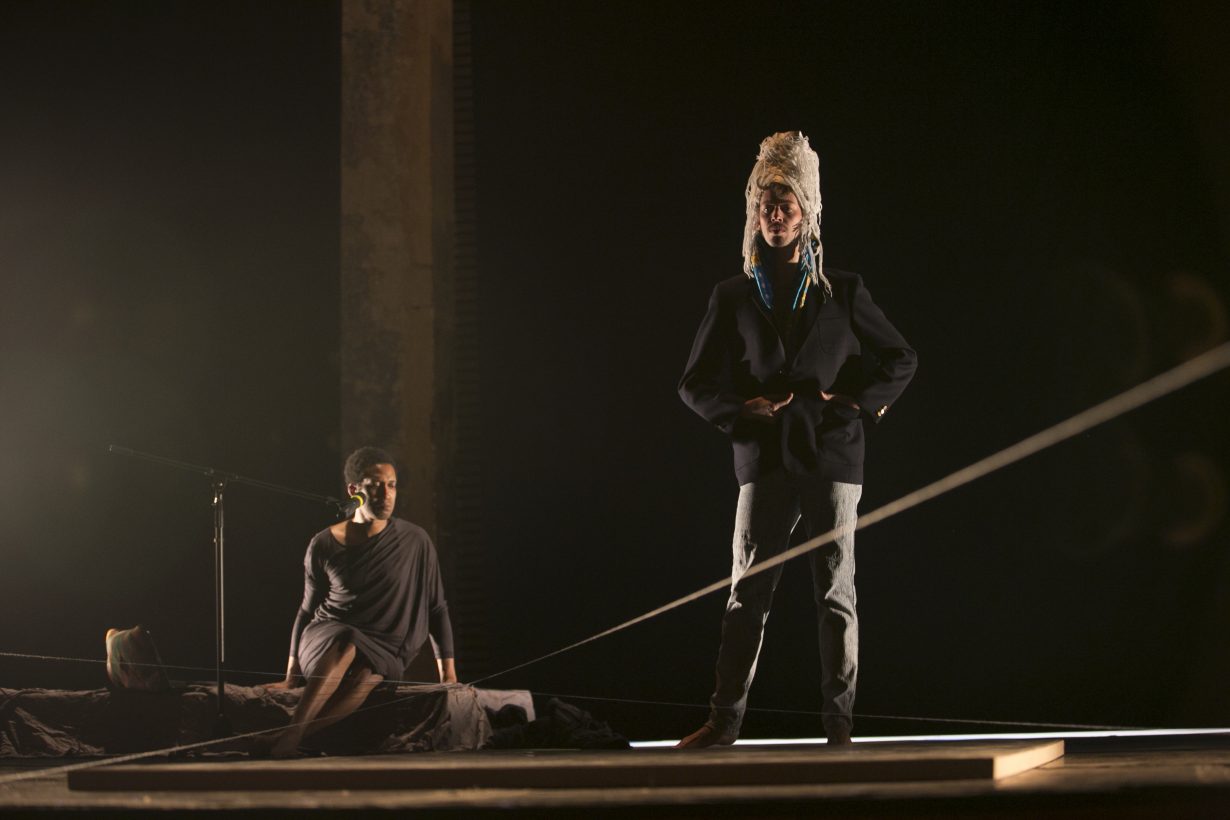

Trajal Harrell’s 2022 trilogy of works, Porca Miseria, were presented at the Barbican, London, on 12–14 May