Snow’s study of the celebrity as an art object reveals something deeper about our relationship to beauty

Celebrity worship is a defining current of contemporary pop culture, and taking celebrity seriously as a purposeful artistic construction is an acknowledgement of the way art and beauty function in many people’s lives. As the ‘artworld’ turns ever more investor-oriented, maybe the celebrity, paradoxically, is becoming the democratised art form because of its universal consumability. I imagine some readers of Philippa Snow’s new book will find it overwhelmingly depressing to think that some of the great artworks of the early twenty-first century might be celebrities. But to me, reframing celebrity through the prism of art feels unexpectedly optimistic.

Snow’s book states its aim in the title: to expand the idea of the art object to include celebrities. But she opens her book with a discussion of the place of beauty in contemporary society and what its relationship to art is, or should be. By starting here, she sets us up to see celebrity itself as predicated on beauty, which it sometimes is, although not always. Sex appeal, hotness and marketability are all entwined in this conception of the sort of celebrity that Snow reads as an art object. The question of whether or not art should have anything to do with beauty is something of a taboo in contemporary discourse, and Snow’s embrace of it as a criteria for the celebrity as an art object sits improbably in contrast with trends in art writing that focus on identity, ideology and other social lenses for reading art.

Snow’s analysis of celebrities is more about the ways in which they turn themselves into traditionally legible fine art than the way they themselves are art objects. She looks at tangible art objects like Richard Phillips’s film Lindsay Lohan (2011), paintings of Leonardo DiCaprio by Elizabeth Peyton, and the Rizzoli coffee table book Selfish (2015), which is full of Kim Kardashian’s selfies. She also writes about the artists who are concerned with depicting or creating celebrity and who have sometimes become one themselves, among them Jeff Koons, Andy Warhol, Marina Abramović and Amalia Ulman. Not only is she interested in beauty, she is also interested in the construction of white beauty standards.

‘Both celebrities and artworks are in danger of not being taken seriously enough by cynics if they are outwardly pretty enough to be written off as purely decorative,’ Snow writes. It is in the ‘enough’ that this book sits: what is ‘seriously enough’, and what is ‘pretty enough’, and who are the cynics who decide? It’s strange the way that art has become the space in which beauty doesn’t matter, given that it was traditionally made for aesthetic enjoyment (among other things). The last century has seen an active rejection of beauty in art as tastes have shifted to prefer concept over form. Our fear of beauty, which is a symptom of modernity, has made us reduce it to signifying shallowness, something pejoratively girly, pedestrian, commodified. Beauty doesn’t equal goodness, but our present discomfort with it in the context of art’s hierarchy of values comes from the long tradition of equating the two.

Snow explicitly disavows this equation, but she also rests her central claim on the idea that the magnetism of beauty is inescapably human. I agree with her, and it’s this aspect of her book that I find truly incisive. The fraught contradiction between that innate human desire for beauty and the toxicity of chasing ever-changing standards of perfection is heightened by our climate of constant scrutiny and a new economy of monetisable fame. Snow’s work opens a new conversation about the complexity of wanting to make something beautiful – including yourself.

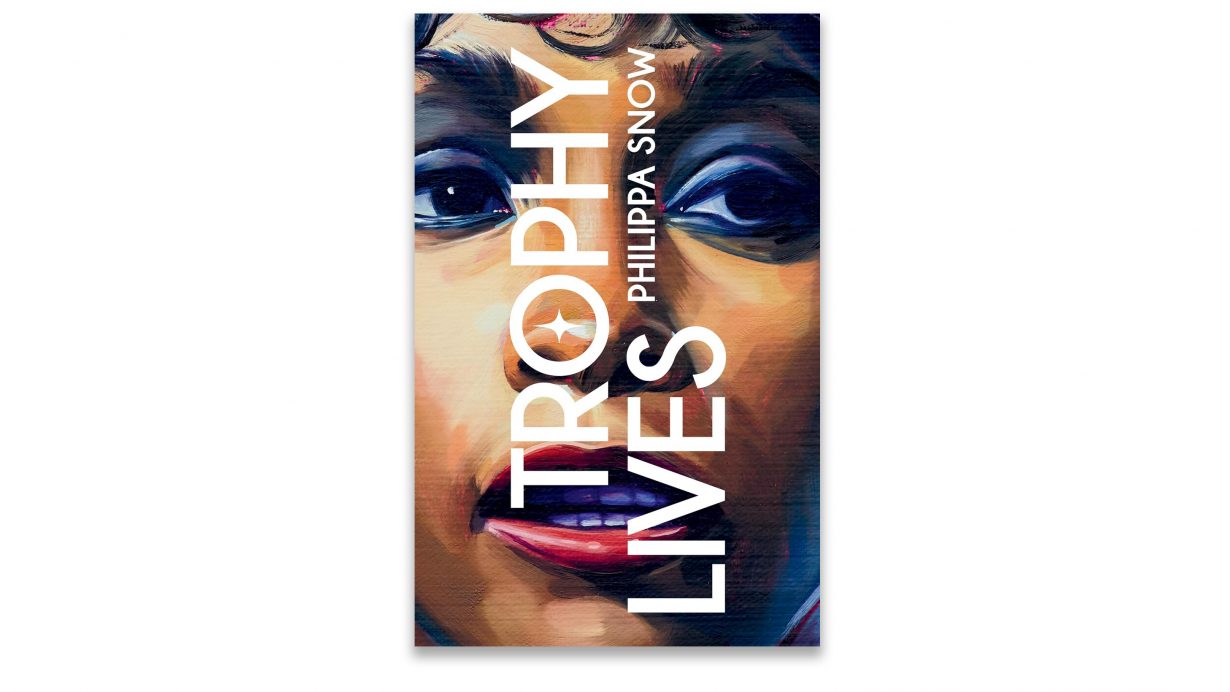

Trophy Lives: On the Celebrity as an Art Object by Philippa Snow. Mack, £14 (softcover)