Is this a moment of triumph or merely a sign of our present psychic malaise?

As queer theory drifts towards its mid-thirties, what better way to celebrate its establishment as an ‘alternative’ mainstream style than the queering of Sex and the City (1998–), another cultural phenomenon in the throes of a difficult ageing process? In the show’s reboot, the friendship group of middle-aged New York socialites – who once threw condoms at men in an Abu Dhabi souk in the name of American feminism – open minds and legs to the zeitgeist, embodied by a ‘queer, non-binary, Irish, Mexican’ podcaster named Che Diaz (played by Sara Ramirez), ostensibly parachuted into the show to atone for its past moral failings – the ‘do better’ mantra by now a familiar excuse for repackaging tired commercial formats.

It has been 32 years since the publication of Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble, a dense academic treatise arguing for a reformulation of the way we understand gender and power that became the unlikely cornerstone for a popular movement. Queerness’s extraordinary journey from the academy to the Che Diazification of culture has much to do with its fundamental malleability. Someone who experiences no sexual desire at all can be queer, a resident gimp in a sex dungeon can be queer, people in nominally heterosexual marriages can be queer. The base requirement for entry – underpinned by a Foucauldian-inspired Weltanschauung in which identity is understood as a political construct, and the reductive narratives told about you must be fought with the emancipatory ones you tell about yourself – is a feeling that you don’t align with what are commonly referred to as normative expectations of gender or sexuality, making it an unusually accommodating prospect in a time when the borders of identity are typically patrolled with militant zeal. Over time, queerness has become a popular replacement for its parent movement, feminism, among those wishing to distance themselves from transphobic factions and the unfashionable connotations of second-wave feminism, as well as for the letters gathered, often uneasily, in the LGBT alphabet. (In the latter case, whether queerness offers greater inclusivity, or whether its popularity has a homogenising effect, is debatable.)

While queerness’s mass appeal carries utopian promise, echoing the socialist agenda of uniting marginalised groups in a struggle against an oppressive ruling class, the reality is an existential malaise, and a blindspot to economic factors such as class and wealth that tend to fall outside the purview of representational politics. In this regard it follows in mother’s footsteps: just as feminism expanded to mean so many conflicting things – from the Lean In (2013) corporatism of Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg to intersectional feminism and the ugly rise of TERFism – that two people who declare themselves ardently feminist may have violently incompatible views, so too has queerness become riddled with contradiction. Does queerness mean working towards a future of ‘somatic communism’ laid out in Paul B. Preciado’s Countersexual Manifesto (2000), where new organs and desires are invented and the means of reproduction seized for collective use? Does it mean ‘influencer-activists’ who treat the self as a startup, advertising their radical credentials in the hope of being sponsored by multinational companies, as if arriving at the gates of Versailles with a job application for the role of brand ambassador in one hand and a pitchfork in the other? Or is it a project of canon-building and historical revisionism facilitated by conservative cultural institutions? Queer collectives and artists, such as melanie bonajo, engaging in public performances of social work and therapy? (In the press material for the Dutch Pavilion at the 2022 Venice Biennale, bonajo is described as a ‘sexological bodyworker, somatic sex coach and educator, cuddle workshop facilitator and activist’.) What about Lil Nas X advertising Uber Eats?

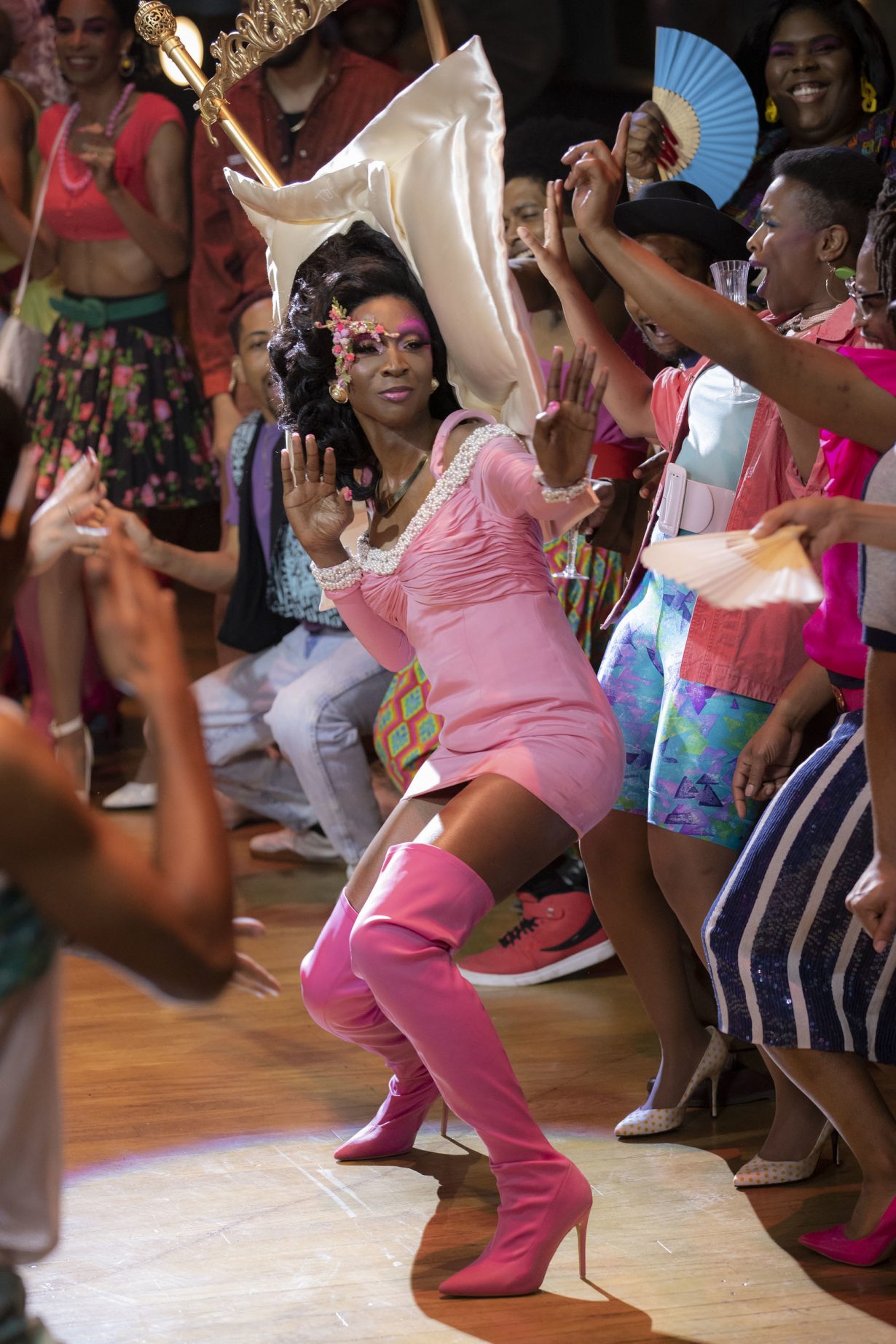

The confusion extends to what is frequently referred to as ‘the queer community’. What, for instance, does a home-owning millennial in London have in common with a competitor at the underground ball scene in 1980s New York, beyond watching the ascendant genre of ‘public service announcement’ television shows like Pose (2018–), and the ‘yass queen’ mannerisms picked up from Ru Paul’s conveyor belt of drag? Materially and experientially, the answer is very little. Often, the binding agent between dissimilar parts is the concept of solidarity, a term that like ‘community’ has been the subject of considerable bastardisation, used to describe para-social consumption habits and a powerful desire to associate with the style and moral authority ascribed to the outsider. During the 1970s the American writer Tom Wolfe named a pre-digital manifestation of this phenomenon ‘radical chic’. Today it might be better understood as a feature of ‘Unicorn Syndrome’: a psychic infection endemic in societies, beset by moral confusion, whose citizens are raised on a diet of self-help and self-marketing. Symptoms include a deep need to be recognised as uniquely interesting, a concomitant phobia of being lumped with the ‘normies’, a compulsion to excavate every wound, secret or point of difference and use it as a USP, and an attitude of moral exceptionalism that encourages a focus on the ways in which we feel injured by power while ignoring the extent to which we may be executors of it.

Over the past three decades, queer theory’s mainstream appeal has been underpinned by its continued influence in Western academia, producing cohorts of graduates aligned with its values and operating as a powerful cultural export. A largely North American professorial class of crossover personalities that includes Maggie Nelson and Julietta Singh have helped improve the public image of the academy by writing popular and intelligent personal accounts of bourgeois queer family life, and the practice of ‘queering’ has opened myriad possibilities for research subjects while unmooring queerness from matters of the body and desire. To queer something is to provide a phenomenological reboot of a subject, an exercise that involves performing a kind of ideological capture. Everything, from the museum, the Middle-Ages, herbalism, the countryside, the economy, colonialism, yoga, the law, and even entire nation states, has been given the treatment. While queering intends to uncover evidence of latent heterosexual bias (and is often successful in doing so), the apparent limitlessness of its application has proved a useful rebranding exercise within and without the academy, where the language of systemic change has been adopted by everyone from museums to banks. ‘We’re done letting the system ignore us’, reads the marketing material for Daylight, a company that claims to ‘queer banking for the better.’ ‘No labels, no explanations, no hidden meanings, no “rights or wrongs”… You are enough’, says a short text on Tate’s website, describing the queer appeal of Yves Klein’s painting IKB 79 (1959) – a work included in Queerate, a digital exhibition curated by members of the LGBTQIA+ public using images from the museum’s holdings during the pandemic. That it is possible to couch a heterosexual artist, whose use of women’s bodies as ‘human brushes’ has long drawn criticism for sexual objectification, in the language of gender fluidity and self-acceptance, exemplifies the extent to which anything and anyone can be repurposed.

It is easy to be lulled into a sense of false security over the permanency of rights and public acceptance, particularly among those indoctrinated by liberalism’s promise of a steadily improving world. In reality, rights are subject to the caprices of political weather, not so much definitively won as constantly negotiated. The UK government’s recent decision to exclude trans people from the Conversion Therapy (Prohibition) Bill, to appease the country’s vocal anti-trans lobby, is a case in point. That queerness is a now a highly visible feature of the cultural mainstream does not mean that it is easy or safe to be queer in every home, street, school or workplace – the disjunct between visibility and security is as much a feature of life in an identity-political climate as the gap between radical aesthetics and societal change – nor does it negate the profoundly revelatory impact that queerness can and does have on an individual’s understanding of self and sociality. Yet in the same way in which it has become par for the course to suggest that the field of literary fiction is male dominated, when in fact it is women authors who have dominated for some time, queerness is frequently mobilised to indicate an underdog status in the Western cultural sector despite fetishistic and extensive representation. As it has become a commonplace to see the word ‘queer’ used as a brand intended to communicate a subversive status that is far from guaranteed, it is clear that the solvent that promised to dissolve archetypes has transformed into another kind of glue.

In a culture awash in depressing reboots of everything from film franchises to fascisms, queerness once appeared as a future-facing movement with a promise to see, be and organise differently. If it is to have any chance of reversing its slide into the Cherry Coke of identity – an auxiliary alternative to the status quo – it will require a committed reevaluation of queer exceptionalism. Mark Fisher argued in Capitalist Realism (2009) that the problem facing countercultures is no longer the danger of being consumed by commercial interests, but being preconfigured by them. What we are dealing with now, he wrote, is ‘precorporation: the pre-emptive formatting and shaping of desires, aspirations and hopes by capitalist culture’. There is no easy answer as to how precorporation might be avoided, other than by social withdrawal, just as there is no door marked ‘exit here’ that can be used to escape the reach of technocapital, but attending to the ways in which commercial interests are worked into the DNA of contemporary identity formation surely constitutes a start.

The cure for Unicorn Syndrome is not to believe ourselves boring or unworthy of attention, nor is it to resign ourselves to tradition or to ignore inequalities. Rather, by attempting to acknowledge the material reality in which we live, and resisting the logic of the identity economy rather than leaning in to it, we may begin to see the extent to which bureaucratic boxes and market demographics encourage us into manageable, and profitable, models of difference – models that occlude the possibility of societal change, and in the end do not allow for much

difference at all.

Rosanna McLaughlin is a writer based in Glasgow