In layered installations, Vangelis Vlahos excavates fragments of Greek history to ask what is considered an event, and when, if ever, an event ends

“When I say that I don’t want to take a position in my work, it’s because I believe that I don’t have one,” Vangelis Vlahos tells me via video call. The Greek artist began exploring Greece’s post-dictatorship political history during the early 2000s, in an attempt to develop a sociopolitical consciousness through his artistic practice. Born during the so-called Regime of the Colonels, when a rightwing military junta ruled Greece, from 1967 to 1974, and growing up amid the transition to democracy, he remembers political discussions carrying a negative stigma. “A passive model of historical memory was largely dominant during the 1980s and 90s,” he recalls – Untitled Knight I (1997), screened in 2023 at the Stockholm School of Economics as part of Magasin III’s film programme Borderland – where outer and inner meet, seems to grapple with that passivity. In a gymnasium, the artist struggles to roller-skate in medieval armour. As he stumbles and falls, his restrictive covering – a metaphor for self-protection – gradually comes undone.

What followed were 1:150 scale architectural models that extended the artist’s confrontation with rigid facades, by interrogating the social, political and economic conditions that have shaped emblematic structures within the built environment. Presented at Manifesta 5, Buildings like texts are socially constructed (2004) comprises five models of European skyscrapers that were constructed under dictatorship or communism. Each model was created by architects based on information gleaned from discussions among amateurs in online forums. Among the skyscrapers is Athens Tower, whose model also appears in the installation Athens Tower (Tenants Lists 1974–2004) (2004) alongside printed tenant lists from between 1974 and 2004, indicating a shift from state- and American-owned companies to (mostly) private Greek firms. The entanglement of national and international interests informs each study. “1992” (The renovation of the Bosnian Parliament) (2006–07) comprises two models of the Greece–Bosnia and Herzegovina Friendship Building, a government property damaged during the 1992 Siege of Sarajevo. Dossiers cover the building’s reconstruction (funded by the Greek state), economic agreements between both countries, and Greek foreign policy in the Balkans between 1992 and 2007.

But Vlahos is quick to emphasise that he’s not a historian. With a focus on the mediated footnotes to Greece’s modern geopolitical history, the artist is not concerned with producing research that contributes to the field of historical study – he works with secondary sources and material found online and through the media, after all. “I am more interested in finding a way to deal with an event and to activate it, if possible, in a contemporary context, and test its impact today,” he explains. Describing archaeology as an ideal metaphor for his process, the fragments of the past that Vlahos digs up are not intended to complete a historical picture – archaeology, after all, produces knowledge built up from an accumulation of objects that inevitably shifts and at times collapses as new discoveries appear. In keeping, Vlahos unearths historical traces to burn holes through official narratives that frame history as a closed book, which in turn treats the public as passive recipients of an established plotline. “My goal is to create an open narrative, an open platform, for anyone to project their own perceptions – if they have any – on the event I’m working through, rather than say how it should be understood,” the artist explains.

A shift from architectural models to photographic assemblages during the late 2000s evolved that open-ended approach, as exemplified by Grey Zones (2009). Presented at the 2009 Istanbul Biennial, 75 black-and-white images sourced from newspapers and magazines are divided into two rows, each depicting details of a Cold War-era vessel. The first is an American drillship, Wodeco, used to exploit oil discovered in the Aegean Sea during the 1970s amid the 1973 oil crisis, which intensified an ongoing territorial dispute between Greece and Turkey that the latter’s invasion of Cyprus in 1974 exacerbated. The second is Koyda, the first Soviet vessel to use state-controlled shipyards on the Greek island of Syros as part of a 1979 agreement with the USSR, which was denounced by the US as ‘precedent breaking’ for a NATO country and soon suspended. Though the conservative, pro-Western Greek government at the time apparently framed the agreement in economic terms, its resumption after the October 1981 election of Greece’s first socialist government, known for its anti-American rhetoric, was clearly political. 1981 (Allagi) (2007), named after the socialist party’s campaign slogan, ‘Change’, commemorates that transition. Images from the archives of pro-dictatorship newspaper Eleftheros Kosmos are arranged on 22 boards spanning the moment the socialists took office to when Eleftheros Kosmos closed in June 1982.

The military dictatorship and the US support it received has cast a long shadow over Greek politics. Buildings that proclaim a nation’s identity to the world should not be misunderstood (2003), a model of the US embassy in Athens designed by Walter Gropius, visualises that shade with a curved wire tracing the trajectory of the rocket that Greek militant group 17 November fired at the building in 1996. Formed in 1975, November 17 was named after the day the dictatorship violently suppressed a student uprising in 1973 – an event that is commemorated annually by a march through central Athens that culminates at the US embassy, which has since been enclosed by fortresslike fencing, demonstrating an enduring, popular suspicion of American power and its imposition on national politics.

IS THERE ANY OVERSIGHT ON OCALAN? (2009–11) and Remains (2011) highlight the extent of that mistrust. The former installation tracks the route taken by Abdullah Öcalan, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party’s founding leader, before Turkish authorities arrested him for terrorism in February 1999. Drawing from the internet and tourist guides, a sequence of 119 photos – of airport buildings and landscape views – on a 23-metre-long shelf, log places where Öcalan unsuccessfully sought political asylum after leaving Damascus in October 1998, including Moscow, Rome and Athens, where his clandestine arrival in January 1999, aided by ultranationalist socialist MPs, sealed his fate. Trying to join the European single currency, the Greek state was put in an impossible position. Despite the Greek population generally sympathising with the Kurdish cause, supporting Öcalan was tantamount to aligning with a US-listed terrorist group and declaring war with Turkey. The secret service was thus tasked with moving him to Holland to request political asylum. Failing that, he was taken to Nairobi, where he was arrested after leaving – either voluntarily or forcibly – the Greek ambassador’s residence.

While Kurdish protests across Europe accused Greece of betrayal, and Greek prime minister Costas Simitis shared blame with Europe’s failure to collaborate on a solution – per the Los Angeles Times, Paris, Bonn, Oslo, Stockholm, Bern, Rotterdam and Kiev all told Öcalan not to bother landing – Remains focuses on the fallout of Öcalan’s capture in Greece. Materials organised according to when his arrest hit Greek newspaper headlines to when his name disappeared from them, tracking the mediatisation of a political scandal, include a dossier related to the Greek economy and stock market at the time, which soon recovered from the initial shock; and seven boards isolating images of foreign minister Theodoros Pangalos, who resigned with two other ministers as a result. The last person to resign was intelligence officer Savvas Kalenterides, who accompanied Öcalan to Nairobi – and, per a CIA journal paper, repeatedly refused orders to ditch him. In the aftermath, he told The Guardian that Athens cooperated with America and Kenya to deliver Öcalan to Turkey. ‘We were the middle men,’ he said. ‘As a Greek, I feel deeply ashamed about our role.’

Yet that intermediary role is an enduring one – as evidenced in 2022, when the Greek state mediated another byzantine international incident. While moored at a Greek port, a Russian-flagged tanker carrying Iranian crude oil was impounded due to EU sanctions over Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Recently renamed Lana after its former title appeared on a US sanctions list due to its ownership by a Russian bank’s subsidiary, Greek authorities released the vessel after finding the ship, which had replaced its flag with an Iranian one, had acquired new unsanctioned owners in 2021, whom the US promptly listed. Greek authorities, acting on an official US request, then seized Lana’s oil, triggering Iran’s retaliatory capture of two Greek tankers in the Arabian Gulf. Finally, a Greek appeals court ordered the oil’s return, a decision the Supreme Court in Athens sustained, thus concluding what was described in the national press as a thriller.

Lana is the focus of This event has now ended (LANA) (2023), the title of which defines a series of works that reflects on ‘what is considered an event, and when an event ends, if it ever does’. Fittingly, it was shown with Grey Zones in Elefsina Mon Amour, a group exhibition curated by Katerina Gregos in the Greek port city of Eleusis, one of the three European Capitals of Culture in 2023, thus uniting three vessels to create a geopolitical constellation across time that seems to answer the question the work’s title poses regarding an incident’s lifespan. The two text-on-paper timelines composing the installation emphasise a temporal stretch. One tracks the political events surrounding Lana from when it entered Greek waters and left, and the other logs contemporaneous weather conditions and changes to the tanker’s draught – the distance from the keel’s base to the waterline – which cargo volume can impact. By mapping the Aegean’s climate, the sea is presented as an event in its own right: a porous context that exists both within and beyond the measure of a single incident.

Vlahos tends to decentre the drama in his compositions – a choice that echoes ancient tragedy, where violence was rarely acted out onstage in order to amplify the conditions surrounding its eruption. “A strong image of a person or event with already strong associations and connotations blocks the ability to see differently, to see beyond them, to see outside of preconceived notions,” he explains. Take Objects to relate to a trial (Nov 17) (2016–17), part of a series on notable court cases. The project departs from a failed bombing attempt in Athens in 2002 that led to the first arrest of a 17 November member and the discovery of two Athens apartments used by the group as hideouts, each filled with incriminating items. But rather than engage with that inventory, Vlahos lists everything that was not included as evidence across framed, printed A4 pages. Common household items like toilet paper, paired with an image of the two flats’ unassuming front doors, seem to humanise – or at least complicate – what the media so often portrays as simply monstrous.

That relatability is contrasted by another set of panels, with photos of the front door of every guest room in the Intercontinental Hotel in Athens organised by floor, presented alongside a dossier naming politicians, such as US president Bill Clinton, who stayed there in 1999. That year, the hotel was bombed by the Revolutionary Cells, killing one, in protest against nato’s un-bypassing air strikes on the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (Serbia and Montenegro) during the Kosovo War. It’s an uncomfortably coy juxtaposition of scales that asks what comparable crimes have been plotted within these many privileged, private quarters. Particularly when thinking about the unofficial meeting in Belgrade that year between former Greek premier Constantine Mitsotakis and Yugoslav president Slobodan Milošević, who had just been indicted for war crimes. A 47-second clip of that encounter is described in forensic detail in the video This event has now ended (May 27, 1999, Belgrade) (2019), with text rolling over an image of Milošević: a format borrowing from cinematic decoupage – a screenplay that includes elements like camera angles – which characterises Vlahos’s recent works.

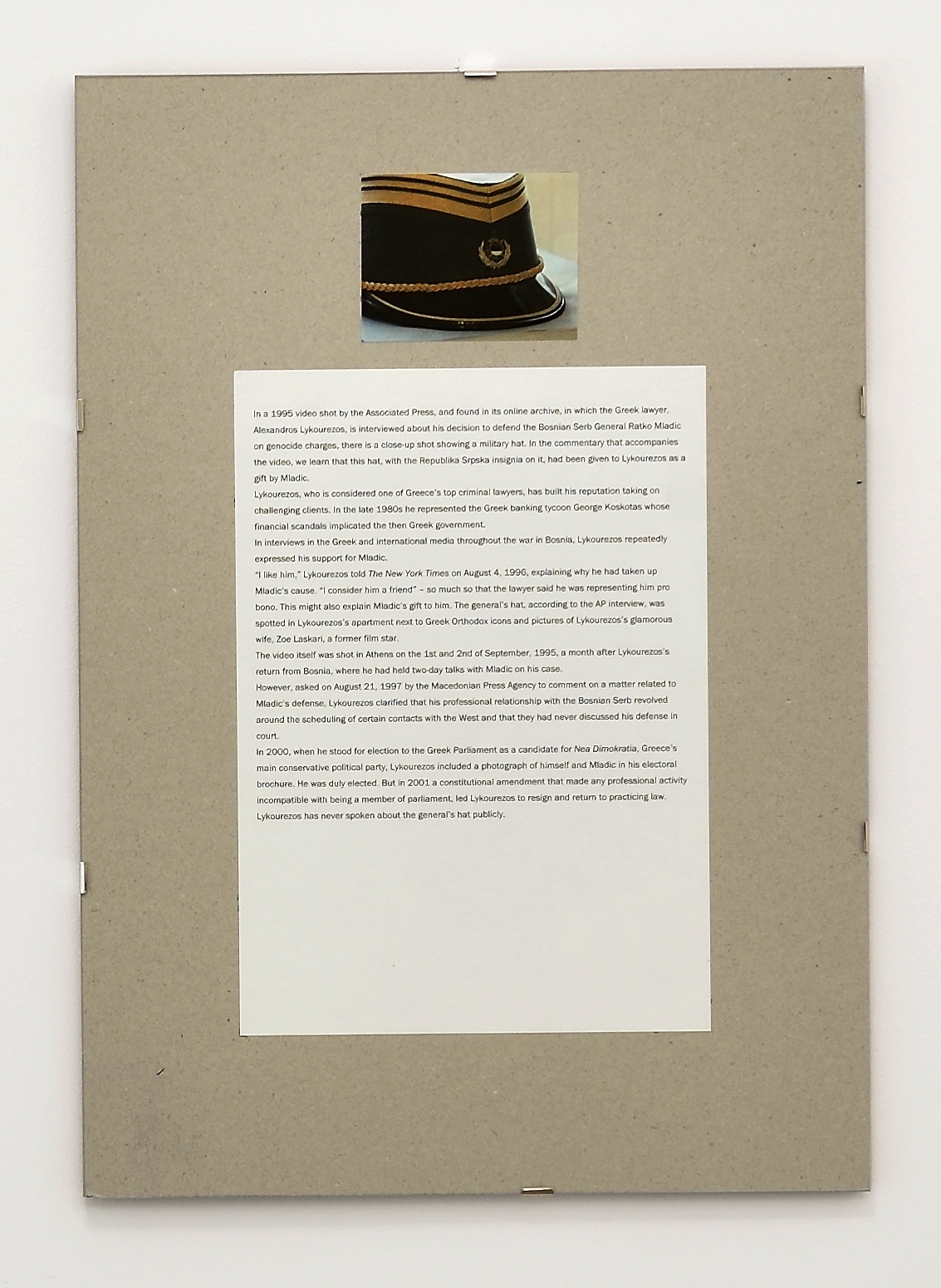

“Greece was maybe the only European country in favour of Serbia during the war,” Vlahos recalls, referring to a relationship between the two nations, tied by history and religion, and which lawyer and politician Alexandros Lykourezos once described as ‘difficult for anybody outside Greece to understand rationally’. Objects to relate to a trial (Mladic’s hat) (2015), a series of image and text panels relating to the Bosnian Serb general Ratko Mladić, confronts that relationship by departing from a military hat that appeared in an Associated Press news clip of Lykourezos voicing support for Mladić, who was charged with (and later convicted of) genocide and crimes against humanity for his role in the Bosnian War – a gift from Mladić himself. ‘What does this mean for Greek politics today?’ Vlahos asks, referring to such dubious connections. He complicates the question by highlighting the changing perceptions of former Libyan president Muammar Gaddafi through the decades; a point that recalls what Vlahos once said about time and place playing a role in how his projects are read.

Of course, Vlahos doesn’t have the answers. “I approach my subjects from the position of someone who does not have a complete picture of the subjects they are researching,” he insists. The Elounda Summit (The differences between the parts are the subject of the composition) (2009), which amasses photos taken by Greek and foreign press at the 1984 meeting at which Greek prime minister Andreas Papandreou mediated discussions between Gaddafi and French president François Mitterrand around bilateral troop withdrawals from Chad, summarises that approach. The work’s bracketed subtitle comes from a 1966 text by Sol LeWitt, which says the artist’s aim is to provide information rather than instruct, and describes the serial artist ‘as a clerk cataloguing the results of his premise’. For Vlahos, that premise is simple: there is never one way to look at something, hence the seriality defining his work. Sequenced like units on a grid, information appears objective because multiple views of a single event have been unified into an object whose visual approximation to a scientific study invites peer review.

The photographic installation This event has now ended (Tsakalotos’s notes) (2016–17), shown at the 2023 Thessaloniki Photo Biennale, expresses that formal sleight of hand. In 2015, Greek finance minister Euclid Tsakalotos – newly appointed after Yanis Varoufakis’s resignation following Greece’s notorious bailout referendum that year – was photographed shaking hands with Eurogroup president Jeroen Dijsselbloem during an emergency meeting in Brussels. In the photo, Tsakalotos, who negotiated new bailout terms in his first week in office, is seen holding his notes to camera, partly obscured by his thumb, with visible phrases like ‘no triumphalism’ and ‘message to people’. This tragicomic incident, which reflects the “hasty and clumsy return to history” that Vlahos observed in Greece with the onset of its sovereign debt crisis in 2009, sparked a wave of speculation on social media, where the image was zoomed in and pored over. Vlahos downloaded these images and arranged them on a panel presented alongside a printed list of words from those notes organised alphabetically, and a timeline of Tsakalotos’s activity that day. Details include the crumpled suit he wore without a tie – another messy footnote presented without comment.

Work by Vlahos is currently on view in Nikos Alexiou. The Collection at the Benaki Museum, Athens, through 26 May; a two-artist presentation of his and Ala Younis’s work is scheduled to open at Tavros, Athens, on 10 October

Stephanie Bailey is a writer and editor based in Hong Kong