Carlo Ratti’s exhibition is a claustrophobic mess of bio and techno theatrics, relying on expensive machines to solve problems that didn’t need fixing in the first place

When Pietrangelo Buttafuoco, journalist and former leader of the neo-fascist Social Movement party youth wing, was appointed president of the Venice Biennale in 2023, the art and architecture worlds collectively clenched their sphincters. What would the appointment of such an ideologue, and the curators he asked to lead each manifestation of the 130 year-old biennale, mean in practice? This week we got our answer, as Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective., the first biennale commissioned under Buttafuco, opened to the public, curated by the architect and MIT professor Carlo Ratti.

The first white man to curate the Venice Architecture Biennale for over a decade, Ratti is a robotics entrepreneur and founder of MIT’s Senseable City Lab, which uses data and technology to speculate about the future of city design. Known for projects such as his robotic cocktail mixologist, and using GPS chips to track trash across the world, he first exhibited at the Venice Architecture Biennale back in 2014, with a contribution rethinking central heating. Instead of convection radiators warming entire rooms, Ratti argued it would be more efficient to heat individual bodies. Instead of handing out cosy jumpers, his team built an array of ceiling-mounted infrared lamps tracking the movement of people below and beaming heat in their direction. It was one of the most preposterous examples of overengineering I have ever seen in architecture. Until now.

The Corderie, a vast 317m-long former rope factory that houses the main site of Ratti’s exhibition, whose intention is to examine the intersection of architecture with different forms of social, natural and artificial intelligence, is packed with tech. There’s a model house clad in astronaut suits, a lunar data centre being built by a robot arm mounted on the back of a robot dog and a humanoid android identical to the one that recently went viral for attacking its engineers. Drones, 3D-printed blobs, endless screens and claims insisting nature and technology are two sides of the same coin abound. Thomas Heatherwick has designed a satellite for growing salad in space.

Architecture shows are often accused of being too dense but Ratti’s Biennale is in another league: 760 contributors, many times more than previous biennales, are crammed together in a relentless succession. In the mix are some promising ideas from architects, artists, technologists and academics that could have made for compelling exhibits were they given space to breathe. Greek artist-collective Vessel, for example, has invented an insulated panel packed with super-low-carbon seagrass. British eco hotshot Material Cultures is showing some of its bio-based housing experiments. A team from the Royal College of Art has made zero energy evaporative cooling towers. But all these subtle works are lost in the wider melee.

In Ratti’s enthusiasm to pack his biennale with as many projects as possible, space has become so tight that many exhibitors are allowed to show just a few photographs, projecting from skinny columns that flank each wall like signposts. Some of the most fascinating buildings to be completed in recent years, such as the child-led Reggio School in Madrid by Office for Political Innovation, are shown like this; relegated to little more than visual noise.

Actual noise has also been turned up to 11. Every room bleeps and clanks in a dissonant, migraine-inducing chorus. Reading the many project descriptions is nearly impossible amid the cacophony. Perhaps anticipating this, the curators have appended a mercifully brief ‘AI summary’ to each explanatory board. But why not simply ask the contributors to submit a short caption themselves? Like so much of the show, the AI summaries are an example of Ratti making expensive machines solve problems that didn’t need fixing in the first place.

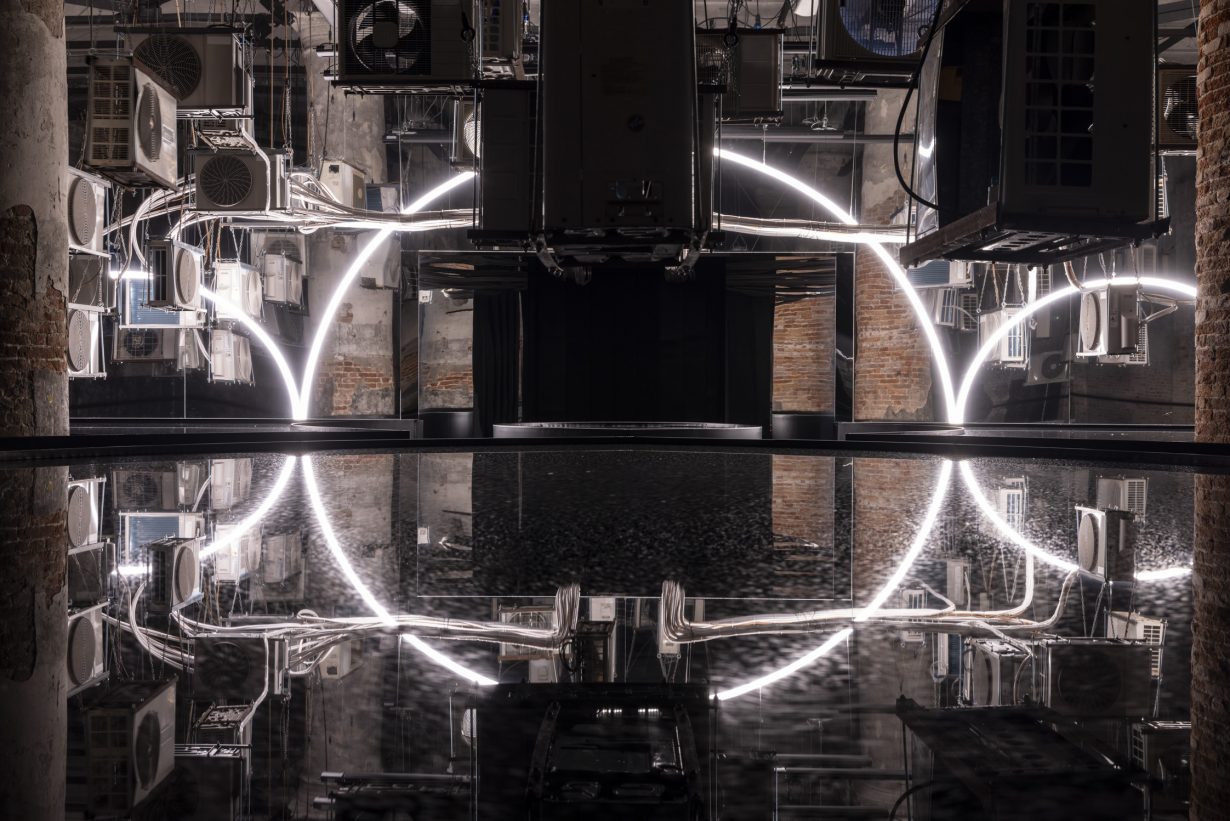

The only exhibit given enough room for a genuinely spatial experience comes right at the start. An array of dilapidated air-conditioning units hang like corpses from a scrapheap gallows. The space is uncomfortably dark and comically hot, encapsulating the weight of heat displaced by aircon used to cool badly designed buildings the world over. It’s the Corderie’s strongest moment. Created by Transsolar, Bilge Kobas, Daniel A. Barber and Sonia Seneviratne, the dangling compressors are actually fake – the heat is coming from hidden overhead radiators – but the feeling they evoke is real.

Outside the Corderie is a pop-up coffee bar serving purified lagoon-water espressos, designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, architects of the new V&A East Storehouse in London’s Olympic Park. Their futurist filtration system, which won this year’s Golden Lion, might have been more impressive if I hadn’t recently seen a friend’s live-aboard narrowboat capable of filtering drinkable water from London’s canals – but at least it allows a moment of respite from the chaos that preceded it.

Look beyond Ratti’s curatorial influence, and the tech-bro fever dream quickly melts away into something far more humane. The national pavilions, which fall outside the scope of the main show’s curator, often feel like a discordant smorgasbord of ideas, yet this year they have an uncommon coherence, including many curatorial tactics that resonate with each other. While the Corderie shoots for the moon, the national pavilions are grounded in more humble themes: refurbishment, materials, social housing and how we people inhabit buildings.

Serbia’s offering in the Giardini is a cloudlike knitted canopy – gently rotating spools gradually unravelling the billowing woollen mesh, winding it back to its constituent yarn in a six-month demolition performance. Around 500kg of CO2 is emitted for every square metre of new architecture, so exploring ways to reuse construction materials is a pertinent concern. The Danish Pavilion also explores demolition, filled with big chunks of floor slab and piles of hardcore from the building itself – a snapshot of the process architect Søren Pihlmann is using to refurbish the twentieth-century structure using as few virgin materials as possible.

The Estonian Pavilion similarly addresses refurbishment, cladding a waterfront palazzo with the same woodfibre insulation that is often inelegantly wrapped around Baltic housing blocks. It’s both a manifesto for more sustainable housing upgrades and a critique of the clunky manner in which they are too frequently delivered. Best of the live repair-led national pavilions is the Vatican’s: an ongoing refurbishment, by architects Tatiana Bilbao and Anna Puijanna, of the Santa Maria Ausiliatrice complex, built in the twelfth century to provide shelter in Venice for pilgrims on their way to Rome. Here, the whole building site doubles as a community centre, providing communal cooking facilities and music rehearsal spaces for local groups. Puijanna tells me that around 100 community organisations have participated so far. Shame, then, that the ambitious act of social and physical repair is undermined by the eviction of its previous occupants, a nursery school, to make way for the pavilion – a detail the pavilion’s architects were only made aware of after its opening for the biennale (they have since vowed to reinstate the nursery within the space). Ironically, then, the Polish Pavilion displays paraphernalia used to make buildings feel safe, from CCTV and fire extinguishers to lucky horseshoes and salt piled in corners. Safety gadgets like burglar alarms are situated on the same spectrum as wiecha, wreaths placed atop newly finished buildings to entice good spirits. It’s a wonderfully warmhearted show, playfully pinpointing the modern superstitions that have crept into security architecture, while giving traditional Polish customs like smudge sticks generous legitimacy.

Ultimately Buttafuoco’s first pick of curator has proved a flop. Carlo Ratti’s dizzying and claustrophobic mess of bio- and techno-theatrics reflects the male-dominated world of Silicon Valley: at best uncritical in its trust of technology and data; at worst a sinister vision of surveillance and automation. The biennale is only saved thanks to the calm and careful curating on show in national pavilions elsewhere. For all its grappling with artificial ‘intelligens’, this biennale lacks curatorial intelligence.

Phineas Harper is a writer and curator covering architecture and design