Fung’s unmannered and deeply personal videos relating to being a gay Asian man in Toronto during the 1980s are finding new audiences

Richard Fung’s work is positioned at the intersection of plural identities, reflecting on the artist’s roots, his sexuality and the Asian diaspora. Fung’s videos eschew immediate categorisation by virtue of their cultural mobility and interest in offering a composite reading of social politics and personal histories through an unpretentious approach to storytelling. In the wake of anti-Asian racism, which has flared up critically in the West during the COVID-19 pandemic, Fung’s work acquires greater relevance for the way it validates Asian lives, specifically those of the most vulnerable due to their gender, sexuality and class. Recently Fung’s videos have been circulating on both sides of the Atlantic, featuring in independent distributor Sentient Art Film’s online festival My Sight is Lined with Visions, LUX’s virtual exhibition Picturing a Pandemic and the programme of Scotland’s Alchemy Film and Arts festival (held online this year, at the end of April).

Fung, born in 1954 in Trinidad and Tobago, when the island was still a British colony, is of Hakka Chinese descent, a heritage he explores in videos like The Way to My Father’s Village (1988), in which Fung recounts his father’s journey from Guangdong to the West Indies in the late 1920s, and My Mother’s Place (1990), a portrait of the artist’s mother, a third-generation Chinese-Trinidadian. After completing his secondary education, Fung moved to Toronto to attend university and eventually became a video artist, writer and professor at the Ontario College of Art & Design University, in Toronto. In 1980 he founded Gay Asians of Toronto, the first Canadian organisation to advocate on behalf of LGBT people of colour.

A few years later he worked on his first video, Orientations (1984), a documentary about the lived experiences of 14 lesbians and gay men at a time when, in Canada, a nonconforming sexual orientation could cost someone both their housing and their employment. The video was initially conceived as a tool to circulate locally to increase awareness of the struggles of the Asian queer community in Toronto, but it was picked up for distribution and programmed at the Grierson and Flaherty seminars, both important forums for independent filmmakers. Relying heavily on talking-head interviews, Orientations actively situates Asian gays and lesbians within the broader – and predominantly white – Canadian queer scene, challenging stereotypes and overt racial discrimination by sharing multiple testimonies of the subjects’ relationships with their workplaces, unions and communities. The video’s lowkey editing and synth tunes accentuate its overall conversational and educational tone, especially in scenes in which the interviewees remember their coming-out and their first contact with solidarity groups, before veering towards the more militant notes of a short section dedicated to the 1984 Toronto Gay Pride parade. With Orientations, Fung also acknowledges the absence of queer Asian men in queer media, paving the way for his critical exploration of gay pornography, both visually, with Chinese Characters (1986), and in writing, with the essays ‘Looking for My Penis’, published in How Do I Look? (1991), and ‘Shortcomings: Questions About Pornography as Pedagogy’, in Queer Looks (1993).

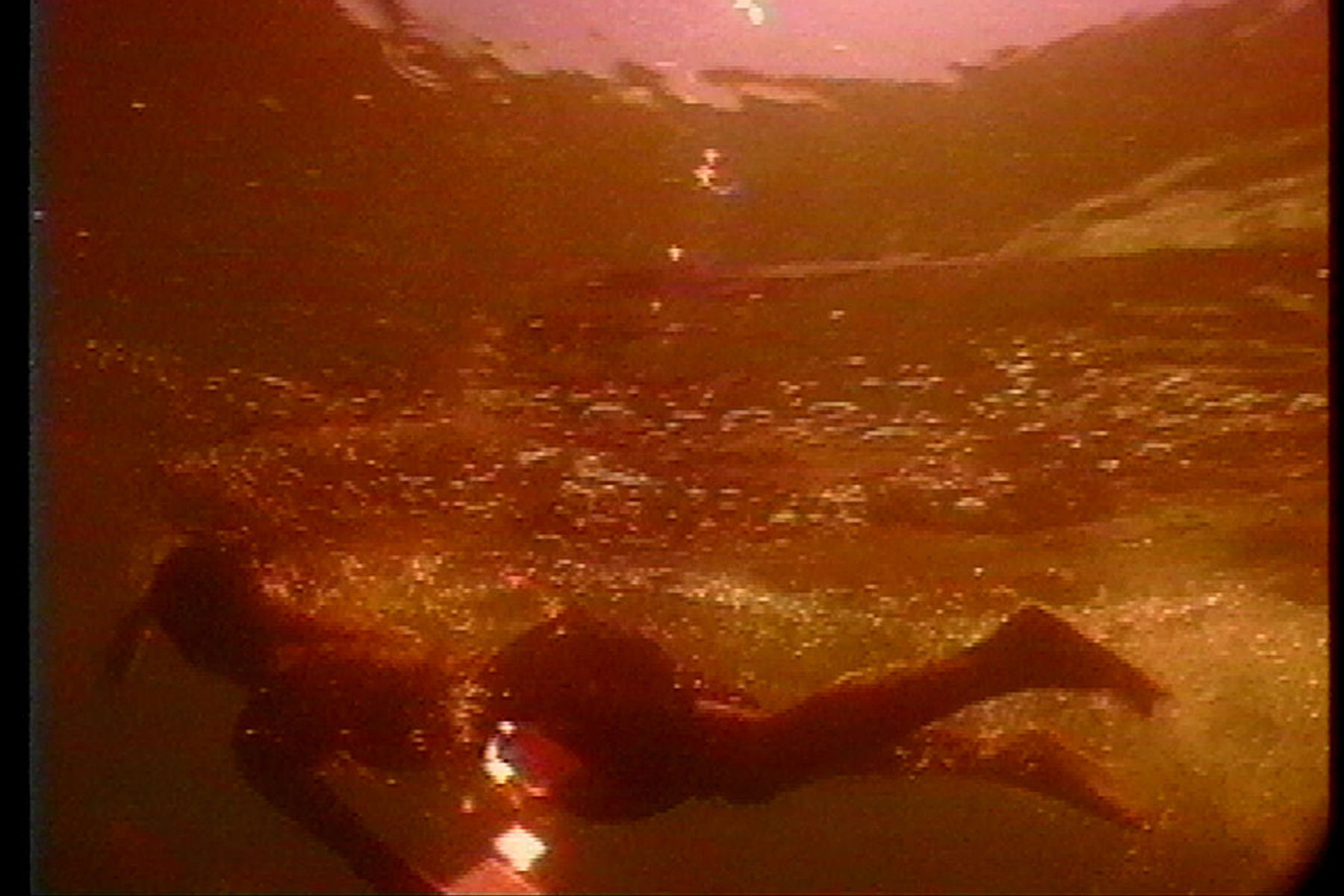

Chinese Characters, Fung’s second video, testifies to the artist’s protean directing abilities as well as his curiosity about making meaningful use of the filmic medium. Inspired by the work of Isaac Julien, Trinh T. Minh-ha and Chantal Akerman, Fung gives Chinese Characters a fresh, experimental edge, mixing fictionalised interviews with appropriated extracts from gay porn videos as well as a brief personal testimony. While commenting on his Chinese heritage, Fung reminiscences about a book of Chinese fairytales a friend of his father gave him. During the artist’s childhood, China remained geographically and culturally distant, despite the stories and the proverbs Fung’s parents passed on. Hence, the fairytale book acts as a bridge to an idealised culture much different, as Fung would learn years later, from the unadorned reality of a diasporic existence. And yet, the ancient tale of an explorer who discovers that the source of the Yellow River is in the Milky Way kept living in Fung’s memory and eventually became the narrative frame of Chinese Characters, enabling the personal and the political to collide.

This parenthetical section gives way to the video’s coda, in which we witness Fung’s mythopoeic power. Since the Asian male queer body is denied an equal place in white gay porn, a new Asian gay epos must be created, one that liberates the Asian man from a subaltern passive role. Carried by funky notes and accompanied by shots of a sunny park, the narrator tells a tale of throbbing desire on an aeroplane. The scene is only sketched, but the characters’ names – Lee and Leung – gesture at a new reality in which Asian homosexuality is not silenced but celebrated. Similarly, a fictional gay romance between two men of Chinese descent propels the narration in Dirty Laundry (1996), a tape set on unearthing the narratives of immigrant Chinese workers who reached Canada during the nineteenth century. Through a stimulating script enriched with archival materials and interviews, the video gives visibility to the queer identities of those labourers society brushed off as ‘bachelors’.

From here a new trajectory can be identified in Fung’s videos. “After I did Chinese Characters, I found my work was being programmed and

I was written about as a gay hyphen Asian hyphen video artist. So I began to feel like I don’t want to be trapped,” Fung tells me during a meeting on Zoom. At the same time, an urge to investigate his own roots seems to be predominant in Fung’s following work. “I began to look at my family because I wanted to use my own story as a way of understanding a larger truth,” he offers, an approach that Cuban-American critic José E. Muñoz described as ‘auto-ethnography’.

Two examples are The Way to My Father’s Village and My Mother’s Place, a couple of incisive, experimental documentaries that take Trinidad and Tobago as a jump-off point to look into divergent stories of immigration that intersect with race, gender and class while navigating the legacy of colonialism and the traps of memory. Near the end of My Mother’s Place, Fung comments on the role his mother has in helping the artist reposition his own identity within a multitude of cultures, and in being the treasurer of an otherwise unknowable past. A similar function is entrusted to Fung’s mother in another tape, Sea in the Blood (2000), perhaps the most autobiographical of all his works. In it, Fung interweaves the familial tensions that surfaced because of his homosexuality with the tragic account of his sister Nan’s illness and death. Sea in the Blood chronicles the trip from Europe to India that Fung and his life partner, Tim McCaskell, took together during the late 70s, which crucially coincided with Nan’s death. The confessional tone of the video is magnified by its bigger scope of embracing in its narrative the overarching colonial dynamics and the political changes through brief references to Trinidad and Tobago’s declaration of independence in 1962 and the Black Power Revolution (1968–70). Also included is a poignant reference to McCaskell’s aids diagnosis, creating an ulterior link to an early tape, Fighting Chance (1990) – itself a continuation of the work initiated with Orientations – in which four Asian gay men openly discuss aids. The video’s political and social importance is unquestionable, as it recentres the discourse around the virus and breaks the wall of silence around the transmissibility of aids among the Asian queer community.

Gluing together Richard Fung’s filmmaking is his relentless drive to question his own methods and motifs, resulting in an undogmatic approach to both film and its finality. “I’m very committed to understanding media and how the media image works,” Fung says, “but then there are certain things with particular urgency to them where I feel that I want to have people not get tripped up by experimentation and the medium.” Questions of race, queerness, colonialism and justice hence become the reference points of a career that spans three decades and counting, in which individual stories serve as a compass for navigating macropolitical forces.

From the Summer 2021 issue of ArtReview Asia