As Celmins opens her new retrospective at Fondation Beyeler, just outside of Basel, Ben Street wonders how close an artwork can ever get to its source material

Vija Celmins’s notebooks provide a running commentary on her lengthy practice in printmaking, drawing, painting and sculpture, and share that work’s persistent, often witty spirit of inquiry. In an entry from December 2014 that epitomises this approach, she wrote the line ‘The “comedy” of finding a double’. What kind of comedy is this? In Nabokov’s Despair (1934) a German businessman meets his exact twin on Petrin Hill in the city Prague, but the resemblance is striking only to him – with comic and disastrous consequences. The double’s mimetic failure, in that he doesn’t quite match up, is the source of the novel’s comedy of delusion. It’s this mismatch that gets us close to the wry tone of Celmins’s work, where doubles and almost-exact copies abound. In another (undated) notebook entry, republished in the catalogue for her 2015 exhibition at the Secession, Vienna, she worries at the nature of her practice: it is ‘re-experience[d], re-created, RE-DESCRIBED’. In her three-dimensional recreations of globes and blackboards, or imagery derived from photographs of night skies and seascapes, Celmins redescribes the natural world as mediated through human manufacture. (A large proportion of this output has been brought together for her retrospective, opening in June at the Fondation Beyeler, outside Basel.) Her work’s many pleasures lie in its insistent made-ness, which opens up a space between the real and its double.

The title of Celmins’s sculptural installation To Fix the Image in Memory (1977–82) feels like an apt description of her approach to artmaking, with its implications of thwarted ambition and unfulfilled desires. In that work, 11 pairs of seemingly identical pebbles are placed side-by-side. There’s no easy way to tell that one of each pair is a handpainted bronze copy of the other, a distinction that touch would easily resolve. Yet at close range, the tiny slips of the making hand give the game away. Celmins’s work demands of its viewers the same kind of scrutiny she herself gave to the pebbles, found in the New Mexico desert, and this attention is rewarded by the imperfections of the redescribed. To Fix the Image in Memory embodies Celmins’s strategies of reenactment that have remained consistent in her six-decade career, from her early paintings of the 1960s to recent works such as Cane (2023), a rose branch, bristling with thorns, uncannily recreated in painted bronze.

‘Picking up photographs is like picking up rocks.’ That’s another line from a Celmins notebook. Finding a double, picking up rocks: in both quotations from the artist, the act of selection seems passive, like scuffing your boot on a stone you end up keeping forever. Celmins’s earliest paintings, made after she had moved to Los Angeles in 1962, appear to refute even that level of selectivity. Using the same austere palette that has remained largely constant in her work since then, Celmins depicted objects that lay around her Venice Beach studio, like an inventory of a young artist’s life-support system: a hot plate, a lamp, a fan, a heater. (‘Just the facts, man,’ as she later said of these paintings.) Yet they reach beyond it too. In Envelope (1964), a torn airmail envelope sits face down on a plain, brown surface, alluding to distances actual and perceived: from her family home in Indianapolis, maybe; from her childhood in Riga, whence she and her family fled after the Soviet occupation in 1940; from the artworld of her time, even, in which she has always seemed anomalous, apart.

These early paintings limn the edges of Celmins’s world. When she does pick up photographs, as she did shortly thereafter, the scenes they evoke are starkly, even comically distant from the hermetic environs of their production. Imagery of actual or implied violence – a man running from a burning car, crashed warplanes, the Watts riots – draw their power from that quality of spatial and temporal removal. The painting T.V. (1964) anticipates the terrain this work would lead her into. The appliance sits in shallow grey space at the centre of the canvas, its screen parallel to the picture plane. On it, an airplane and assorted debris fall out of a grey sky: an apparition of the wartime context of her early childhood in the present of her Los Angeles studio. The formal and emotional possibilities of that screen became the governing metaphor in the work that followed. It is as though the context of the studio interior fell away, distilling her output into a single-minded address to vision and its limitations.

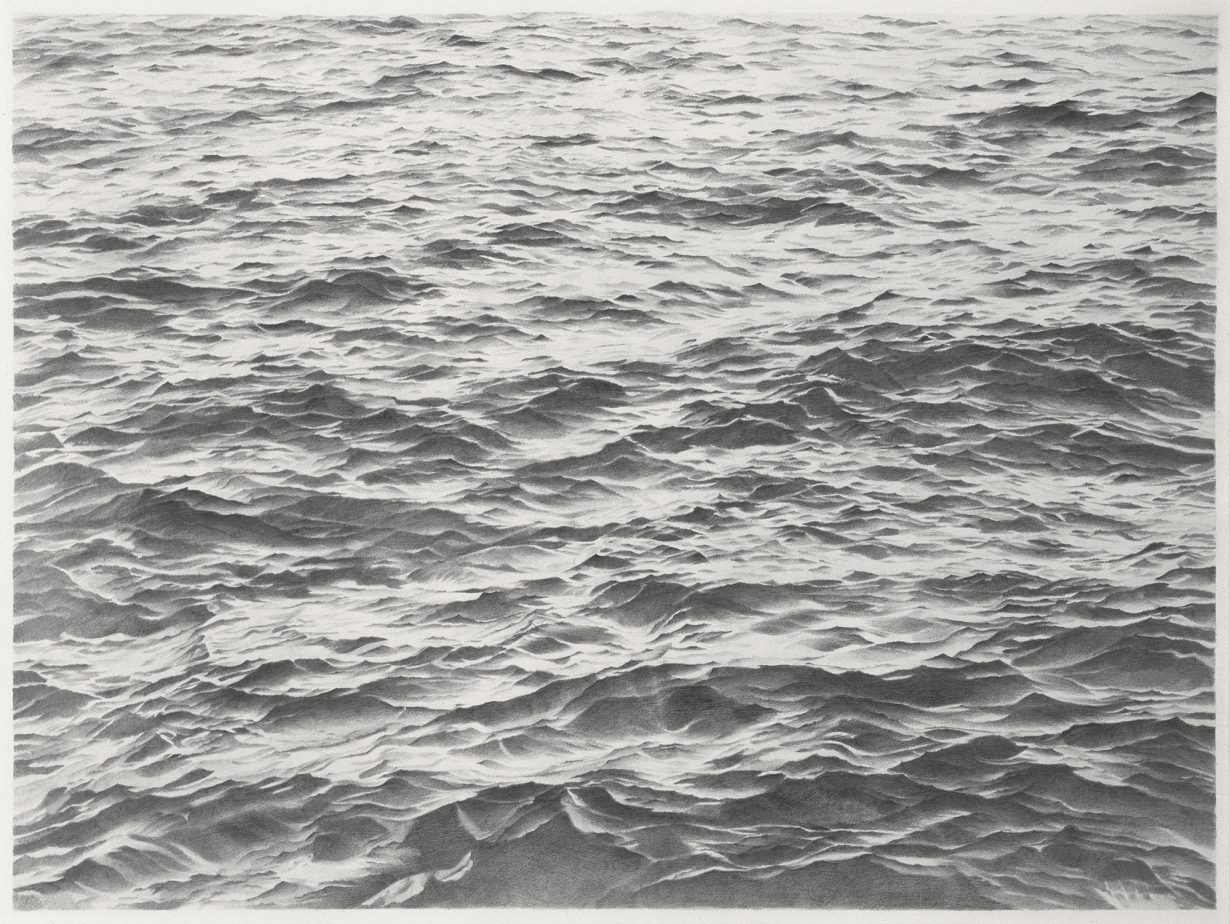

The moonscapes, desert fields and seascapes that followed at the very end of the 1960s are filled, end to end, with a sustained mark-making that, like the raster system of a television screen, is brimful of visual incident. Their closest kin might be the graphic works of Georges Seurat, whose conté drawings dissolve the whole visual world into a hail of static. That relentless visual availability, what Norman Bryson, writing about drawing’s affordances in general, called ‘a radically open zone that always operates in real time’, perhaps accounts for Celmins’s abandonment of painting for over a decade, starting around 1970, in favour of a resolute dedication to work on paper. What drawing in particular provided was a site of constant presentness that resists translation into words. The soft marks that invoke the focal edges of the photographic source for Irregular Desert (1973), for instance, drag the viewer’s attention towards the loose array of stones at the centre, yet nothing in particular awaits you there, aside from the careful tracks of a patient eye and hand. Attention is the subject, and the expectation.

In works on paper such as these, Celmins made use of images that (as she later put it) ‘mapped out and followed the surface’. What you get is a kind of sounding-out of mark-making’s expressive range. In a seascape drawing like Untitled (Big Sea #2) from 1969 – which is, by Celmins’s standards, huge: 86 by 113 centimetres – the visual experience toggles between two surfaces: that of the page, and that of the immense expanse of water that fills it. Writing two and a half centuries after the birth of J.M.W. Turner, the temptation to dust off allusions to the sublime is hard to resist. Yet it’s because Celmins’s work so insistently returns us to the site of the studio that the reference fails to convince. The marks of the burin, pencil or lithographic crayon remain so present in the encounter with Celmins’s seascapes that the apparent subject seems less important than the means by which the work came into existence. Such images summarise the spirit of Celmins’s enquiry as a whole: after all, what’s a better embodiment of the limits of visual representation than the seascape? Get close, as the work requires you to do, and you’re at the studio table with her, redescribing the photographic description, butting up against the artwork’s inability to get close enough to what it shows.

Celmins’s return to painting during the 1980s coincided with an expansion into imagery that seemed to emerge from the rich density of oil paint and the fuzzy weave of canvas, replacing the outward breadth of the paper surface with the inward depth of paint applied in numerous layers. The large painting Barrier (1985–86), one of her first major steps in this direction, is close to four square metres of deep black sky, punctuated by pale dots of varying sharpness. Lacking a clear sense of orientation – because it reads as square, it might just as easily be hung the other way around – as well as scale, it’s a painting of something as seen through disembodied vision, like that of an unmanned satellite or errant drone. Led as ever by what her mediums allow, Celmins’s paintings imagine her dense layering of paint, occasionally sanded down and repainted, as somehow parallel to the unknowable depths of night. In her recent series of Snowfall paintings (2022–24), Celmins’s redescriptions of her photographic sources parse the gap between the world and our images of it. Suspended for the moment in imaginary air, the flakes of snow – themselves embodiments of the unique image, in that no two are ever alike – encapsulate the hubristic urge to reproduce the visual world. We’re here to fix the image in memory, they seem to say: then melt.

Vija Celmins is on view at the Fondation Beyeler, Riehen, through 21 September

Ben Street is an art historian, lecturer and writer based in London

From the Summer 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.