How will a virtual artworld resolve its VIP problem?

Artworks must be feeling lonely right now. No gallery-goer to observe them, no collector to purchase them. Faced with the disruption of lockdown, galleries, institutions and art fairs are scrambling to use technology to keep channels open to their public, be they the collectors who drive art fairs and commercial galleries, or the wider public who see art but don’t buy it, as galleries and art-fair halls remain deserted. The past week alone has seen megagallery Hauser & Wirth launch its virtual exhibition of works at its yet-to-be-opened ‘art centre’ on the islet of Isla del Rey, Menorca; Frieze is throwing open the doors to its ‘Frieze Viewing Room’ (8–15 May) to replace its cancelled New York edition; and even resilient regional art gallery Hastings Contemporary has been able to inaugurate its new exhibition of much-loved illustrator Quentin Blake, with the aid of an online telepresence robot that navigates the otherwise empty galleries for remote viewers.

If these often hastily developed experiments in virtualising the traditional artworld experience of objects and spaces demonstrate anything, it’s that even big artworld players are just as novice in responding to the new conditions as smaller outfits with fewer resources. No one knows how these initiatives will succeed, and what these very different projects starkly reveal is how the exclusivity the artworld and art market once depended on has been disrupted by the fact that there’s currently nowhere physical to exclude people from, during the time that everyone is working with the same combination of confinement and digital distancing.

Comically, exclusivity has had to be reinvented. There is, after all, something faintly absurd about the ‘VIP’ preview of Frieze Viewing Rooms, where, without a VIP code, one can’t access the 200 galleries, institutions and nonprofits that get to present the works they couldn’t in New York – until the ‘public’ viewing that opens on Friday. The habits of physical exclusivity die hard, since the key aspect of such art-fair privileges is who gets priority access to gallerists and first choice of works – something once enforced by the schedule of ultra-VIP, VIP and ordinary access to fairs.

But without a big tent or an exhibition hall, virtual fair editions can’t be much different from online shop-window platforms such as Artsy: it will be interesting to see how the world of online viewing-and-buying platforms might shake out in the coming year, as the big fairs have to retool themselves as prestige online viewing rooms, encroaching on the territory of these other established platforms. And as the physical constraints and costs of art-fair exclusivity dissolve, there’s no reason why commercial galleries shouldn’t form alternative assemblies to reboot the online viewing-platform under their own control. After all, the oldest contemporary art fairs, such as Art Cologne and Art Brussels, were started on that basis.

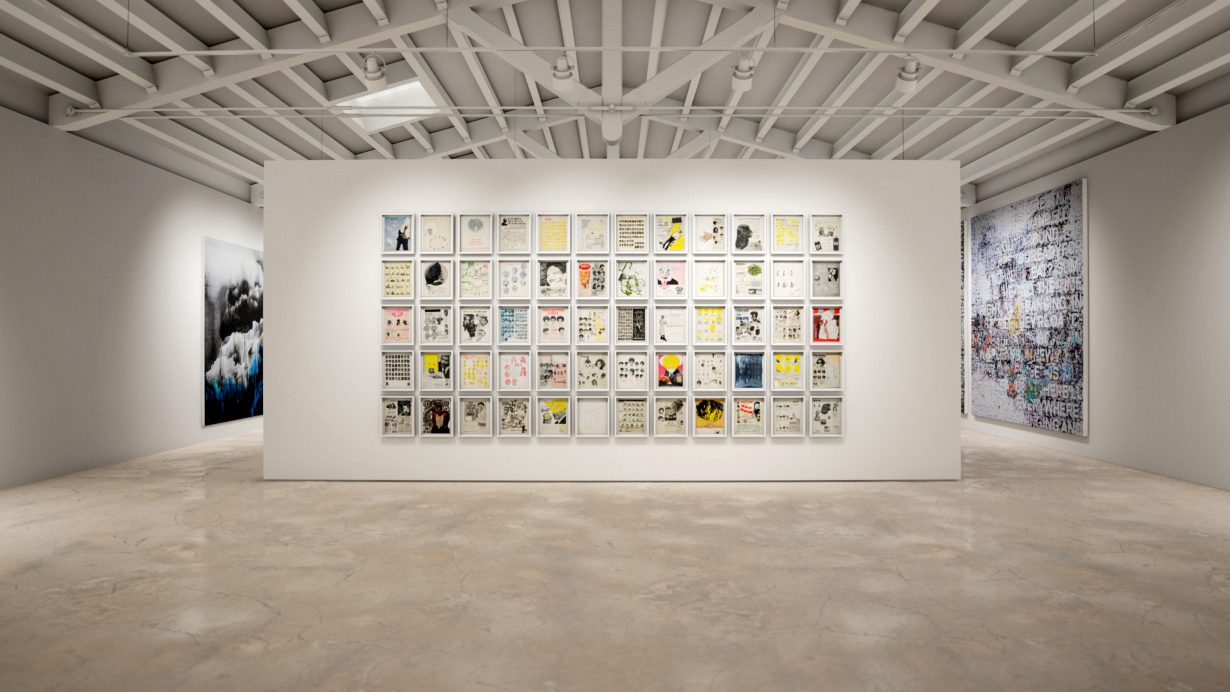

Physical exclusivity, then, will likely evolve new forms as the tempo of the global art fair circuit stalls. And in the world of megagalleries, the contradictions of accessibility and exclusivity are entertainingly confused in Hauser & Wirth’s first foray into VR-exhibition making, in its staging of Beside Itself, the first outing for its ‘HWVR’ virtual modelling platform, showing what a show might look like in the new galleries of its Menorca art centre – an eighteenth-century former naval hospital – when it’s eventually completed.

Trumpeted as a ‘first in in virtual reality exhibition modelling’, and apparently using a ‘bespoke technology-stack not found in any other industry’, Beside Itself is actually rather clumsy – as VR gallery viewers go, it’s no match for a Matterport rendering (this writer’s current favourite). As one only jumps from one spot in front of a work to another, with no transition in between, one quickly loses sense of orientation, and it’s impossible to get a closer look at the blue-chip works hanging on the pristine walls. Perhaps that’s not the point. After a while of reading the caption for a work by, say, Jenny Holzer or Ellen Gallagher, rather than looking at the work itself, you’re dizzily wondering which end of the gallery you’re at, and how to get out into the sun.

Of course, Beside Itself is more than anything an advert for the soon-to-be-complete architectural elegance of the Menorca complex and, by subtle hinting, of the rarefied tastefulness of this tiny island, the bucolic architecture and the lush gardens that will underpin the experience-value of the centre – one that, while pitched at the local community, will equally offer prestige viewing conditions for those sojourning in the Balearics, who might want to drop in to make a leisured purchase from Hauser & Wirth.

‘The community’, or ‘ordinary people’, as they’re sometimes known, are also shut out of art galleries, particularly public institutions, many of which are facing financially precarious futures. It’s a fair distance from the sunny shores of Menorca to the beaches of Hastings, in Sussex, but it’s worth noting Hastings Contemporary’s launch of its new show by the artist and children’s illustrator Quentin Blake, not least for its use of a physical viewing ‘robot’ – a remotely steered video-camera tablet mounted on a Segway-like wheeled base. It’s another technology that’s been around for a while – California outfit Double Robotics has been making its telepresence robots since 2013 – that’s been pulled into the art context. This writer isn’t sure that a gallery full of robot viewers is the future – not, at least, on a choppy wi-fi connection – but the desire to make physical artworks shown in situ accessible remotely should be cheered – it’ll just need better cameras and faster connections.

All these initiatives presuppose that artworks should continue to have a physical presence, even if accessed remotely. To see a great work in all its detail without going to the far side of the world is, pandemics or no, a great possibility. These developments also hint at how the culture of privilege and exclusivity – a constant background condition of art’s culture – will likely evolve towards conditions where physical sites of presentation become, for those who can afford it, more rarefied and more private. In the near future, collectors won’t just be buying a work, but access to the place to go and see it.