More than a decade after his death, the artist continues to unsettle, judge, mock and disappoint

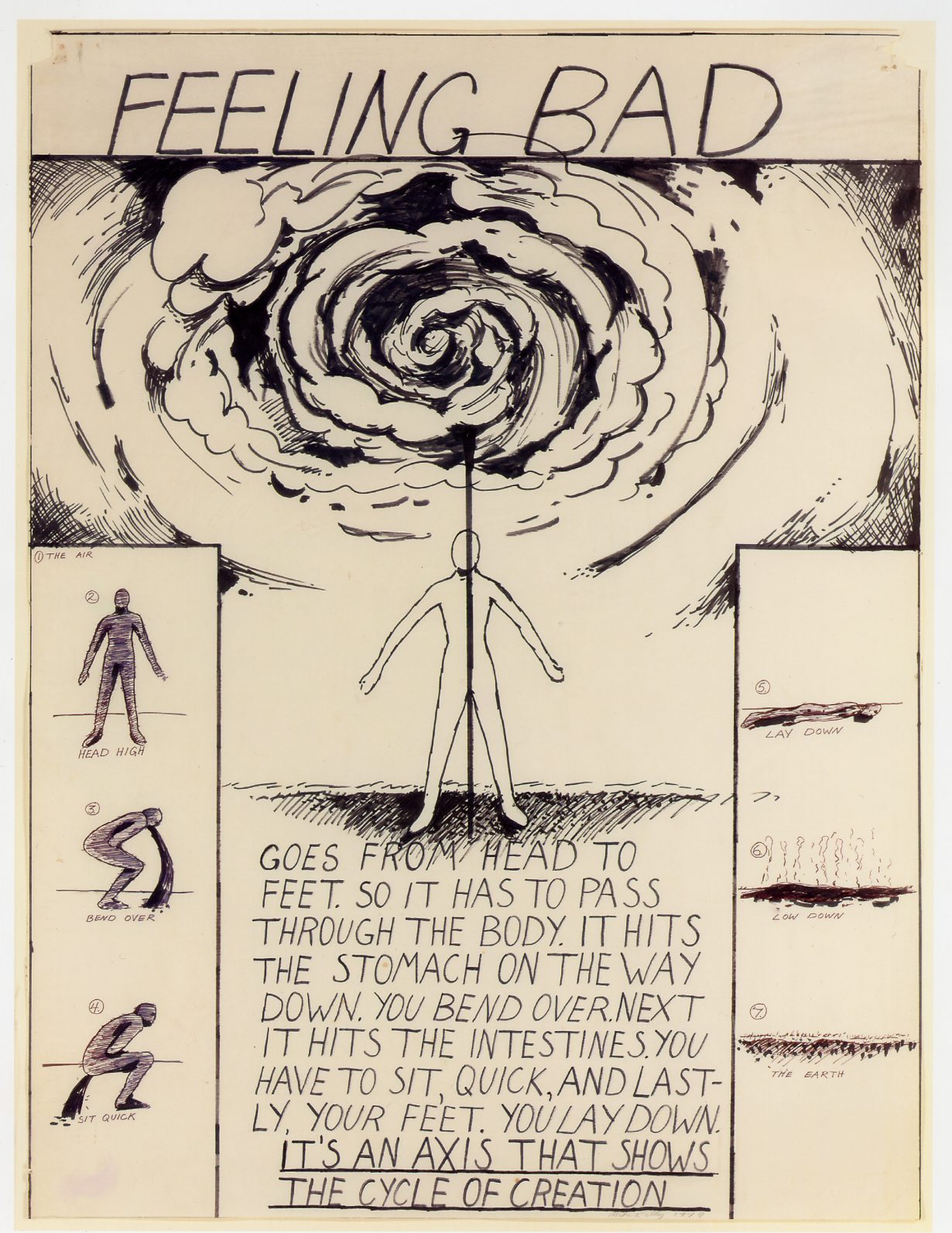

Monstrous worms made up of the knotted limbs of faded stuffed-animals, the room-high stretch of their bodies an uneven patchwork of old polyester fluff dotted with dozens of wide, cartoonish eyes staring blankly out at us. Interminable films featuring amateur actors in outlandish costumes – a witch, a devil, a farmer – running through the motions of some rambling script, the narrative too cryptic to hold prolonged attention. Crude line-drawings of disproportionate, odd-limbed figures, often with faces that are much more scrupulously detailed than the rest of their bodies. (In my head, these, more than anything, mostly convey a sneer of disappointment, or just unalloyed disgust.)

Encounters with Mike Kelley’s artworks always feel partial, fragmented, unsettled; you sense that those creatures are judging your incomprehension, judging your feeling that something was missing from the work, judging your inability to tell what was missing and what, exactly, was staring you in the face. It’s been over a decade since Kelley’s apparent suicide, and this autumn his second posthumous retrospective (his last began at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum in 2012, and travelled to the Pompidou Centre, MOCA LA and New York’s MoMA PS1 over the course of the following two years) begins its slow journey around the museums of Europe, dredging up the possibilities of more quixotic and erratic encounters with his work. And as is usual with such largescale outings, the inevitable bluster: ‘one of America’s most influential artists’, the blurb for this latest show touts, as his work getsparcelled into broad themes such as ‘memory’, ‘social classes’ and ‘the abject’. Don’t believe the hype.

Despite my unease, I return to Kelley continuously. Or perhaps there are several Mike Kelleys to which I return continuously. The first is Proto-punk Kelley: spikey, alert, ready for rupture and twigged to the nuances of confrontation. Offered the conventional slot for a conventional bio at the back of a catalogue of his work in 1991, he instead wrote a tongue-in-cheek portrait of himself in fragments: ‘Some Aesthetic High Points’ recounted winning a high-school art-prize for a deliberately botched painting, then waxed excitedly on the manipulative skills of Sun Ra and Iggy Pop. ‘He played the audience like a fish,’ he gushes about Iggy repeatedly playing Louie, Louie to a bar full of disgruntled bikers.

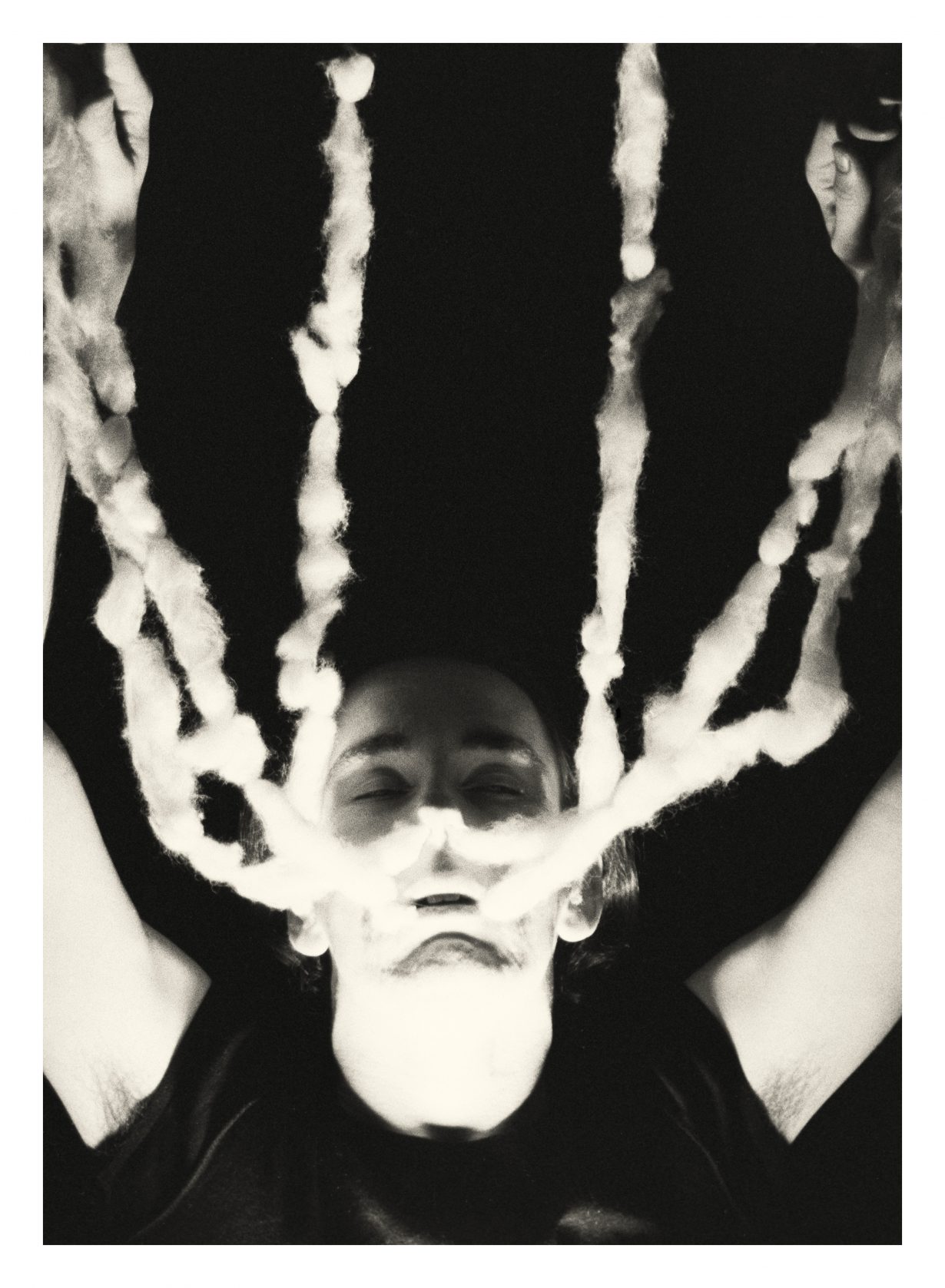

It was through his writing that I first encountered Kelley, so of course this punk persona was my first impression, as the antiauthoritarian and sceptic he projected throughout the diarrhoeic and incessant discourse about his own work. Later, when editors would ask me what art critics I enjoyed, Kelley was always one of the first names that would spring, unbidden, to mind. As a driftwood student – making comics and scraps of video and not writing very much – I chanced on a book on Kelley’s work in a library, and reading his words came with the woosh of a first-time-sensing that ‘art’ – the stuff shown in hushed galleries and written about in hefty tomes – might hold some connection to actual life and possibilities that felt relevant and alive. Art could hold music and comics and film and explode outward still. I didn’t get all the references that he crammed into the texts or the art, but I could feel the crawling suburban unrest and righteous petulance rising out of it all like the muck that Kelley depicted steaming out of his own nose in the Ectoplasm Photographs series (1978/2009). I didn’t get what might link Plato’s Cave, Rothko’s Chapel, Lincoln’s Profile, as one 1985 exhibition was titled; but seeing an image of the painting Exploring (1985), a large black-and-white depiction of a stalactite- and stalagmite-riddled cave, rendered in a shadow-heavy style reminiscent of the drawings of Charles Burns, with it, I could imagine seeing punk’s contradictory impulses – its own snarled, spitting, voguing and subjugating in the name of egalitarianism – play out as a three dimensional funhouse. The painting, infamously installed with a gap beneath it, blocked visitors from accessing another area of the show unless they followed its diktat to ‘CRAWL WORM!!’

At other times, I turn with a shudder to the Kelley that might be an inverse: the Postpunk Kelley, world-weary, apparently accepting of his place in an art-market star-system, celebrated by museums and showing like clockwork with blue-chip galleries such as Gagosian. The solo shows I finally got a chance to see were flat, sterile, with none of the energy that the writings claimed for the work; gleaming with an overproduced shine, emboldened with theatricality without direction, screaming silently into oversize rooms, as if held in the vacuum of the bell jars he was incessantly displaying. I distinctly remember a photo portrait that accompanied one of the show announcements: Kelley wearing a purple trenchcoat and wide sunglasses, looking for all intents and purposes like a latter-day Van Morrison, swollen, leering and aloof. There might’ve been a joke in there somewhere, but the veneer of art-establishment dignity killed any irony.

For a long time I took that as a lesson about the gap between talk and walk; an instruction to be wary of artists’ overinterpreting their own output. As Controlfreak Kelley put it in the preface to the anthology of his writing Foul Perfection (2003), his words were ‘a response to my dissatisfaction with the way my work was being written about critically’. I have found that letdown goes both ways: encounters with standalone Kelley works remain an experience defined by disappointment.

When I actually encountered Exploring in person, as part of Kelley’s first posthumous retrospective in its Centre Pompidou incarnation, in 2013, there was no crawl space underneath it; it was just hung among a bunch of other paintings, salon style. The painting’s exhortation seemed hollowed out, cutesy. But that exhibition introduced me properly to Disingenuous Kelley: a Janus-faced entity happy to present one thing while doing another; going through the motions, powered by spite, weaving a wide-spanning, immersive web of dismay. The sheer kaleidoscope of actions and attempts, performance remnants next to dead-end doors; bird houses that offered their inhabitants two entrances: ‘the easy road’ and ‘the hard road’; splotchy intestinal paintings; faux-naïf cartoon scenes alongside interviews with musicians and filmmakers. He may have worked with any medium that came to hand, from paint to PA systems, but it was all part of one big installation. Each part of it, each work, was a deliberate failure, as if to acknowledge the absurdity of how art attempts both to embody and to mess with the hierarchies of cultural influence. Which means, to put that into the corporate-tech terms used these days (just to spite Kelley), that the disappointment is a feature, not a bug.

At other points, I’m struck by Kelley the unrepentant Freudian, working with heavy-handed metaphors of hidden encounters and long-suppressed memories, and ever quick to roll out the psychiatric lingo. Kelley seemingly treated every aspect of American culture, from school plays to discarded toys, as evidence of repressed memory syndrome, that all around us were signs of oppression and denial. Even hiding in plain sight in the urban-drive-by mundane were weighty symbols of oppression. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve thought about Peter Schjeldahl’s offhand comment in his 2012 obituary of Kelley, about how a set of his early white rectangular paintings were reflective of how graffiti was painted over: ‘For Kelley, these were ciphers of repression both social and, by a formal association, aesthetic – indicting abstract painting for a similar denial of raw feeling, on a historical, grand scale’. Highway-side graffiti, or an adolescent basement bedroom, or an elementary school auditorium stage, or even Superman’s destroyed home-planet, Krypton: all were primal scenes, sites where youth acted out its formative moments and endured its foundational pressures and traumas. These sites were Kelley’s launchpads, onto which he would then overload an excess of issuances and outbursts that would become the work. Most emblematically Freudian, his Mobile Homestead (2010) recreated his childhood home in Detroit. On the surface it was an open-use community centre, complete with a hidden, subterranean warren of chambers, accessible only to invited artists, that mirrored the above-ground suburban layout. (He was, publicly at least, damning about the project: ‘As public art, intended to have some sort of positive effect on the community in proximity to it, it is a total failure… The work could become just another ruin in a city full of ruins,’ he wrote in 2011.)

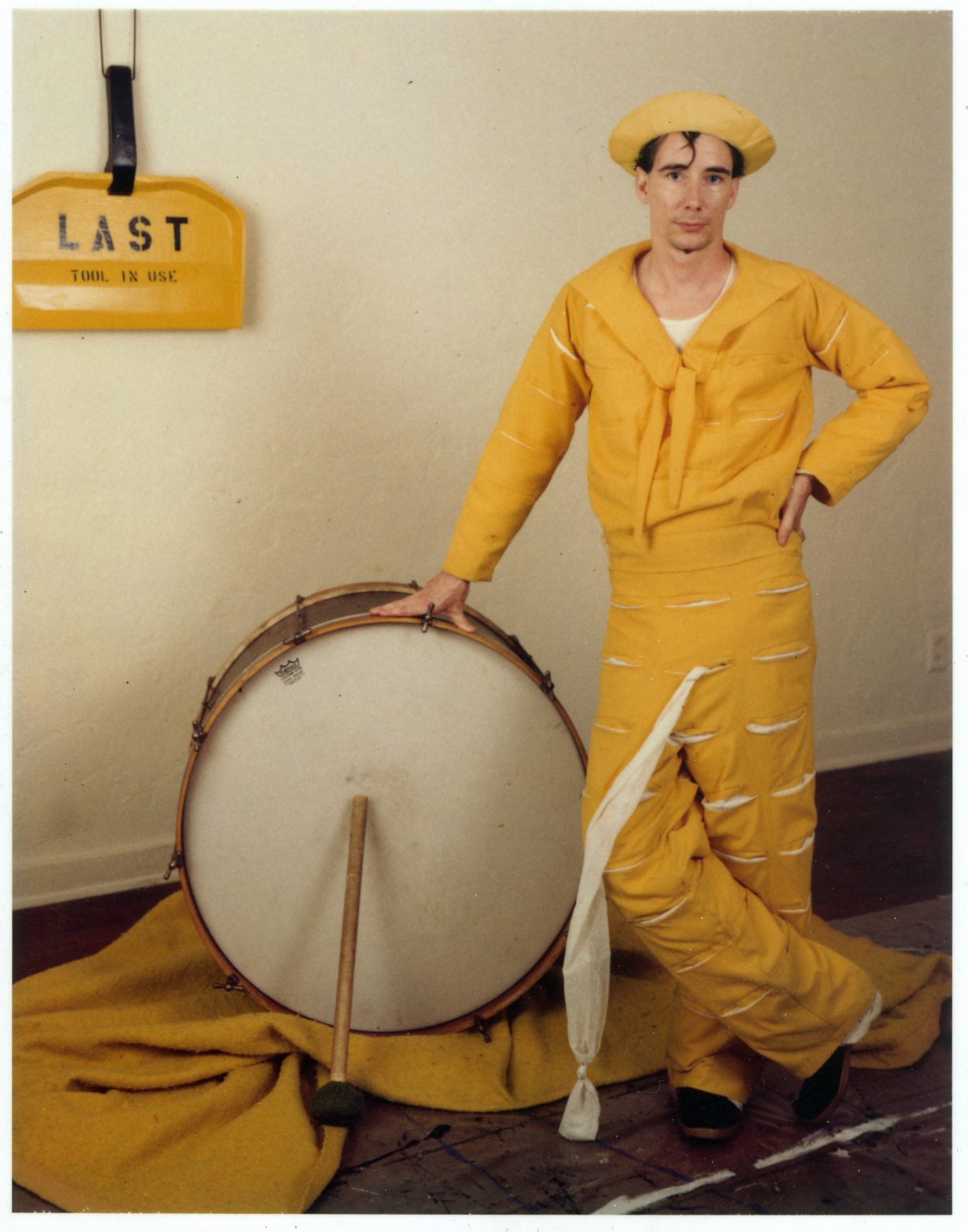

Day Is Done (2005–06) is his most sprawling, patchy and distracting body of work, extended from an understanding of schools and education institutions as both perpetual prisons and memory palaces. But from that acute insight, the project holds an unfathomable set of 365 videos, which used photos of student plays and performances from old yearbooks as scripting starting-points, enmeshed, as if that wasn’t enough, with Kelley’s personal memories and pop-culture moments. Extravagantly dressed and correspondingly stiff actors creepingly act out mumbling scenes, amidst props and installations that brought some of the yearbook scenes to uncertain life. The project becomes, in some form, an appropriate monument to suburbia, a fragmented tribute to the flimsy activities made up to pass the time and to the pasts we’ve tried to forget. Which is to say, it becomes its own museum, yet another educational institution. Forming a central part of this current touring retrospective, Day Is Done is an almost too accurate portrait of the dead ends of youth: awkward, limping, painful to watch. Though I’m still not sure if that keeps it from slipping into the authoritative framing that a museum retrospective creates, as if trying to nail Kelley into one coffin, labelled Canonical Artist.

Something between the works and his writings still kicks up dust. There is no resolving these several Kelleys; and I’m sure all those who experienced the work or knew him, or other errant readers, have other Kelleys to which they turn. I’m weary of any institution claiming a Kelley singular, as if there’s a coherent whole to grasp. Perhaps I’m just a rube taken in by the deliberate personae of a Dungeonmaster Kelley, controlling behind the scenes; though I take some kind of consolation in the something – elusive and heartfelt – that still slips out between all of Kelley’s postures. And perhaps what a retrospective like this provides isn’t so much the chance to meet these Kelleys, or even for a flush encounter with Kelley’s restless and patently ridiculous work. What it might give is a chance to return to, and refract, some of the questions I feel Kelley left behind and that his work continues to pose: can you make big, ‘serious’ art about subcultures, or is that just a douche-baggy oxymoron? Are the suburbs even worth the paean that Kelley has made for them? All while taking it in in yawning museum halls, yet more wings of the educational complex he was so obsessed with mapping. So is it even possible to call bullshit on the sanctimonious puffery complex in which the museum plays a part? In the end, I can’t decide if it’s the work itself I’m looking forward to seeing again (in yet another configuration), or just the people walking out of the show, with spit in their eyes and fish on their faces.

Ghost and Spirit is on show at the Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris, through 19 February