The year in books: Beyond the marketing trends, 2024 offered a refreshing reminder that the life of many texts is cyclical

‘The year in books’ really means the year in the publishing industry: nobody wants the proliferation of ‘books of the year’ lists to include what people really read (dogeared charity-shop Penguin classics, old favourites in hard times, books you got for Christmas four years ago that have finally reached the top of the pile on your bedside table), but rather a broadly similar selection of the shiniest new releases of the year, primarily published in English. Books, seen in this way, are products to be marketed, and they spawn their own commercial descendants. When Irish novelist Sally Rooney’s fourth novel, Intermezzo, came out in September, much of the discourse that surrounded it was to do with the merchandising decisions made by its UK publisher, Faber, hoping to capitalise on the wild success of her previous novels, which have sold more than six million copies: t-shirts, tote bags and pin badges adorned with variations on the distinctive navy-blue graphics of the book’s dustjacket. In the US, its American publisher FSG threw a ‘book premiere’ for the novel in association with the Hollywood actress Emma Roberts, which included a chess-themed friendship bracelet ‘station’ and a branded photobooth.

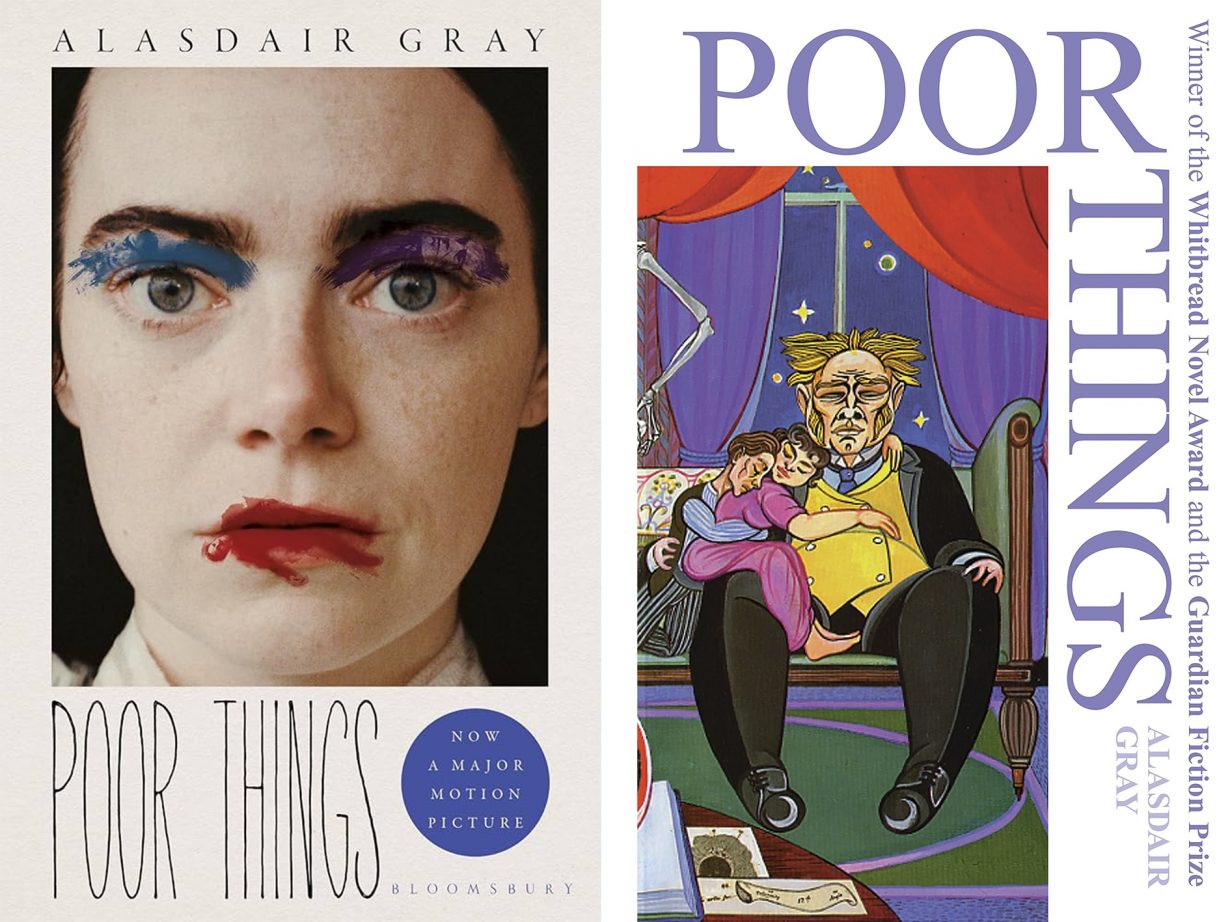

In recent years, much has been made of the A-list infiltration of literary fiction, with actresses Sarah Jessica Parker, Reese Witherspoon and Kaia Gerber choosing books to talk about on their powerful social media profiles in a way that either marks a death knell or a boon for the genre, depending on your point of view. In a slightly less star-studded incident closer to home, the glistening cover of Polly Barton’s translation of Asako Yuzuki’s excellent novel Butter recently appeared as an accessory in a promotional video for Marks and Spencer. My own personal books-as-products grudge, meanwhile, is how the new cinematic tie-in cover of Alasdair Gray’s Poor Things (1992) replaced the intricate, idiosyncratic genius of its author’s own drawings with Emma Stone’s much more marketable face.

Rooney, however, holds herself generally apart from the hype that surrounds her novels (she was not in attendance at the Intermezzo ‘premiere’) and is mostly interested in using her fame to draw attention to her political principles, especially in her consistent speaking-out against the ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people. She also, lest we forget, writes interesting novels, and Intermezzo itself considers, among other things, Wittgenstein, polyamory, and the life of Christ. In this respect, it was in good company among other splashy yet inventive novels published this year that have appeared on prize shortlists and bestseller lists, including Miranda July’s ecstatic treatment of menopause, All Fours, Rachel Kushner’s eco-spy thriller Creation Lake, Samantha Harvey’s luminous space odyssey Orbital (winner of this year’s Booker Prize), and James, Percival Everett’s subversion of Huckleberry Finn.

My own novelistic pantheon of the year is a weird and spiky constellation, populated by Holly Pester’s cartwheeling, exuberantly existential book about the ‘irreducible non-existence’ of the precariously-housed, The Lodgers, Hannah Regel’s quietly assured tale of ceramicists and disappointment, The Last Sane Woman, Yasmin Zaher’s bold saga of a Birkin-bag pyramid scheme, The Coin, Balsam Karam’s completely devastating The Singularity, translated by Saskia Vogel, and Maya Binyam’s Hangman, which has an opening I believe I will never be able to forget. All of these latter books engage, to greater and lesser extents, with questions of private property, financial precarity, immigration and the transgression of borders: fiction, in 2024, dwells in the realm of the political.

Three nonfiction books published this year addressed similar questions of action and inaction under capitalism, and how to read the marks it leaves on us: Anna Kornbluh’s Immediacy, Or The Style of Too Late Capitalism, which divided readers upon its publication in January, and Hannah Proctor’s magisterial Burnout: the Emotional Experience of Political Defeat, which, in a year coloured by electoral horrors and apathy, offered a way of thinking through despair. Isabella Hammad’s Recognising the Stranger: On Palestine and Narrative, the text of her 2023 Columbia University Edward W. Said Lecture published with a new afterword a year on from the event, weaves its literary critical apparatus into an urgent intervention in the Palestinian struggle for liberation. ‘Nonfiction’ is a strange formal category, containing as it does all the books you find on the tables at the front of large chain bookshops that might as well be labelled ‘Nonthreatening Gifts for Dads’, and uncategorisable hybrid works, book-length essays, and collagic experiments in memoir and analysis. Two such books, Marianne Brooker’s Intervals and Annie Ernaux’s A Woman’s Story, evidence the joys of intellectually ambitious creative nonfiction (and demonstrate beyond doubt their publisher Fitzcarraldo’s ongoing commitment to it). Both are attempts at telling the story of maternal life from the perspective of a daughter; both exhibit in different ways a cerebral rigour that is digressive, personal and experimental.

One area of the publishing industry which remains, for the most part, stubbornly unprofitable is poetry, though I’m wary of making any sweeping sentimental statements about the relationship between poetry as a form and its resistance to easily digestible marketisation: poetry gains nothing from empty validation of it as a de facto ‘radical’ genre. When I needed reminding of that this year, I turned to Luke Roberts’s Living in History: Poetry in Britain, 1945–1979, a remarkable book which troubles the exclusionary margins of ‘British’ poetry and reads poems as ambivalent texts, with complex relationships to their political contexts. Having said that, there were collections of poetry I read this year which reawakened my sense of what the form can achieve at its best: Rachael Allen’s virtuosic lyric account of tandem emotional and environmental decay, God Complex, Anne Carson’s Wrong Norma, a facsimile edition of Carson’s own illustrations and annotations, Oli Hazzard’s archive of ‘batshit relations’ Sleepers Awake, Gboyega Odubanjo’s distortion of the Book of Genesis, Adam, Nisha Ramayya’s glitching sonic experiment in polticised listening, Fantasia, Danez Smith’s reckoning with the events of 2020, Bluff, and Mosab Abu Toha’s extraordinary poetic document of life in Gaza, Forest of Noise.

At this point, a necessary confession. I find it particularly hard to detach from the shiny clamour of end-of-year lists this year: my own first book came out at the end of August, and clicking on anything vaguely related to publishing trends feels like being drawn to touch a hot stove with no gloves on. Yet within this strange experience is a clarifying reminder of the disjunct between the time of a book’s publication and the time of its reading: a life raft against urgency. Republication, although not free of the industry’s desire for novelty, offers a soothing reminder that the life of some texts is cyclical, and the market for ‘rediscovery’ can, sometimes, offer a map to buried treasure, especially given the growing interest in texts in translation, and translation as a literary practice in and of itself. I’ll finish, then, on books I enjoyed out of their time this year: Pushkin Press’s reissue of Theodor Fontane’s brutal, thwarted Bildungsroman Effi Briest, translated by Hugh Rorrison and Helen Chambers, and Gwendolyn Harper’s new translation of the Chilean writer and performer Pedro Lemebel’s cronicas, The Last Supper of Queer Apostles; a new ‘classic’ edition of Gillian Rose’s memoir Love’s Work, and reissues of Janet Frame’s disquieting novel of post-colonial migration, The Edge of the Alphabet, and Edward Said’s The Question of Palestine. My year in books, then, was also 1895, 1962, 1995, and 1979.

Helen Charman is the author of Mother State: A Political History of Motherhood (Allen Lane, 2024)