And by ‘it’, I mean a film with the nuclear potential to wreck the minds of 15-year-olds

There are pretty low emotional stakes in a Wes Anderson film, or at least all of them since around the time of Fantastic Mr Fox (2009). Even as someone who cries at the smallest provocation, I personally can’t imagine leaving the cinema after an Anderson film of the last decade having been moved to tears, or feeling a bracing, renewed sense of the struggles inherent in being alive. Which is fine. Sometimes things just look nice and are entertaining. But I can’t help but feel a little unsatisfied, watching these perfectly confected movies which have this slight deadness at their core, a reluctance to get deep about anything.

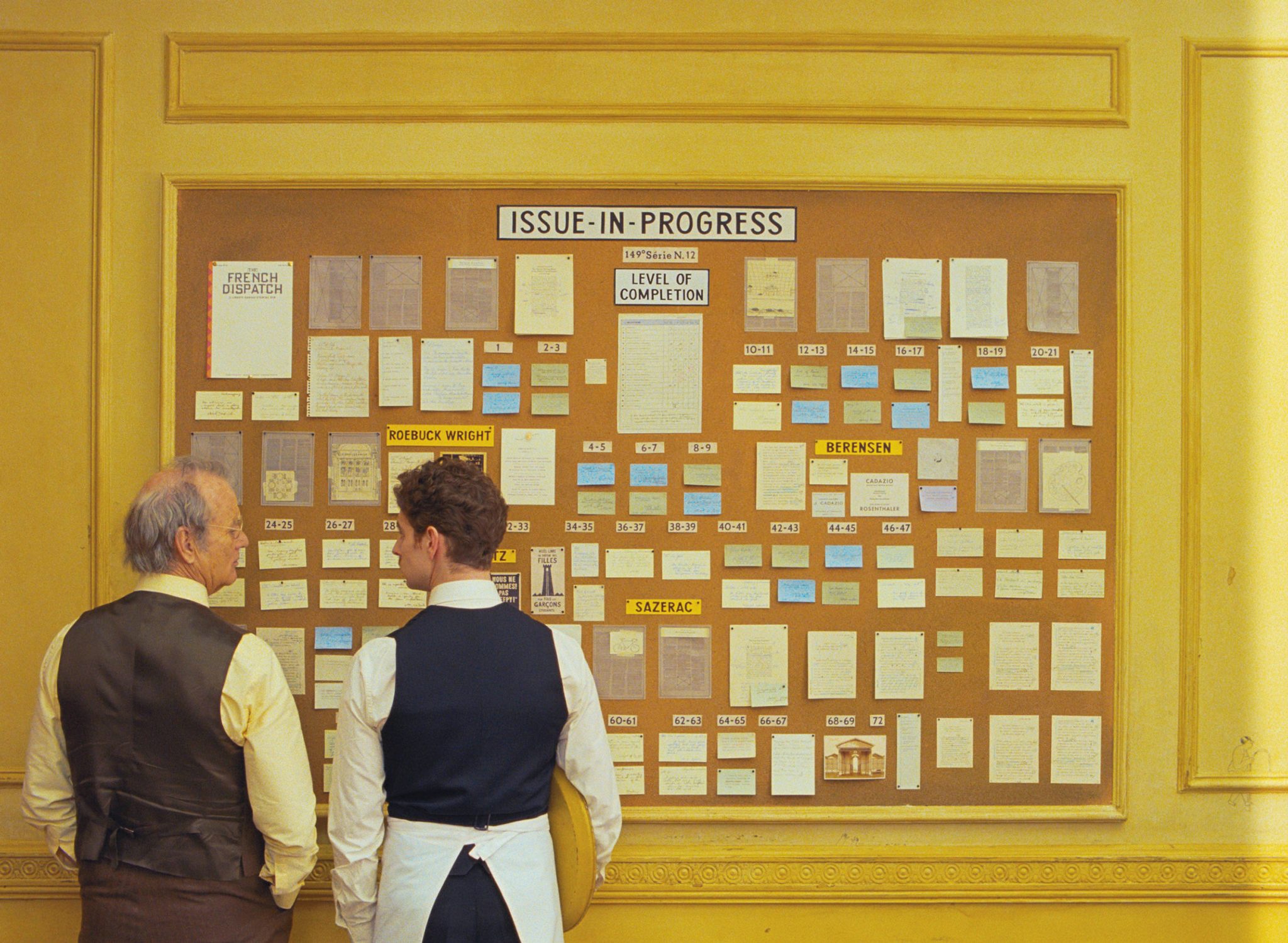

With his latest film The French Dispatch (2021), Anderson has done it again. And by ‘it’ I mean produced a film with the nuclear potential to wreck the minds of fifteen-year-olds and condemn them to a year of ostentatiously reading legacy print-media under a tree in the park while wearing statement hats and forcing themselves to smoke. Gorgeous colour palettes, artful close-ups of coffee cups, fancy French cigarettes, cheap French wine, trilling bicycle-bells, typewriters, wooden chess sets, Pentax cameras, leather messenger bags, Timothée Chalamet in a bath, the word ‘victuals’. The combined effect is a certain kind of cool that might intoxicate a teenager, but it’s a cool that leaves you cold.

The French Dispatch is a homage to The New Yorker, a magazine apparently very dear to the director’s heart. According to a slightly smug and characteristically self-mythologizing article in The New Yorker itself, Anderson is the proud owner of a significant collection of back issues, and has long been an admirer of the magazine’s legendary roster of writers. Indeed, many of the characters in this film are closely based on some of these figures: Mavis Gallant and James Baldwin, for instance, as well as a few of its more famous editors. We follow these people, based in a fictional French town, Ennui-sur-Blasé, as they work for a stand-in publication for The New Yorker called The French Dispatch, which is supposedly an outpost of a small Midwestern newspaper, just to ramp up the quirkiness.

The film itself is made up of dramatizations of four stories from one issue of the magazine. Owen Wilson, an eccentric travel writer, gives us a kooky tour of the town. Tilda Swinton, playing an (eccentric) art critic, tells the story of an outsider artist and incarcerated murderer. Frances McDormand plays an eccentric reporter who gets too intimately involved in the story she’s writing about a student movement, and finally there is Jeffrey Wright’s pseudo-Baldwin figure who gives us a tale of a kidnapping and a virtuoso chef attached to a police precinct. Needless to say, he is also an eccentric.

I think I have a relatively high tolerance for whimsy, but the whimsy here is a lot, even by the director’s standards. And it’s a much more sanitised whimsy than the richer, more engaging weirdness that verged on actual nastiness in something like Rushmore (1998), say. Sometimes it feels as though Anderson is just phoning-in quirk these days. A prison guard is bribed with a single, delicately wrapped marron glacé, the imprisoned artist (Benicio del Toro) has an odd, Paddington-esque growl he makes when he is displeased, and the name ‘Ennui-sur-Blasé’ is just… embarrassing.

On one level, you might think that Anderson’s filmmaking style would be a perfect fit for the iconic magazine – his movies have increasingly felt like an excuse to put beloved actors in nice clothes; films that feel more like a magazine spread than a film with their visual flatness and stylish outfits. Sure, The New Yorker’s signature aesthetic shares with Anderson’s movies a particular kind of sophisticated tweeness. And the film hammers home the connection about as hard as it possibly could without The French Dispatch being called The New Yorker. There are sections animated in the magazine’s signature cartoon style, mock-up New Yorker-style covers intercut with the movie, and a dedication at the end to the magazine’s writers. But how about the writing? That, after all is The New Yorker’s whole thing. There’s nothing in this film to hold a candle to the magazine’s best pieces, something that is all the more queasy for the fact that Wes Anderson collaborated on a published anthology of them to accompany this film called An Editor’s Burial. None of the stories in The French Dispatch are particularly gripping or even interestingly told, and so the film ends up being about style rather than substance. What we get left with, then, is the aesthetics, coupled with starry-eyed, nostalgic caricatures of some of the magazine’s legendary contributors, all the mythos and none of the meat.

Am I being a bad sport? Am I not being fun, wanting this movie that is about print journalism to say something about print journalism? People who really love Wes Anderson films are annoying, but so are people who really hate them, so there’s a tightrope to be walked here. I didn’t even dislike The French Dispatch. I still got that warm Anderson ‘hey, it’s that guy from that other movie’ feeling from all the cameos. But not only because it’s an anthology film, which almost necessarily has to cover a lot of material at the expense of depth, it all just felt a little – forgive me, but the goal is wide open – blaśe.