A new show at Raven Row, London charts the evolution of Bertolt Brecht’s practice, and reenlivens his plays and films as tools for raising political consciousness today

Bertolt Brecht is one of a handful of twentieth-century writers who created such a distinctive body of work, and achieved such fame, that his name has become an adjective. Like ‘Orwellian’ or ‘Kafkaesque’ (and, to a lesser extent, ‘Beckettian’), ‘Brechtian’ – invoked whenever artists remind audiences that they are watching something constructed – is now so widely used as to lose virtually all meaning. This divorces Brecht from his background, the extraordinary cultural richness of the shortlived Weimar Republic, and his aims, to use theatre and film as tools for raising consciousness about how the cyclical crises of capitalism inevitably lead to war.

A new exhibition at London’s Raven Row, Brecht: fragments, charts the evolution of Brecht’s practice, defined by its fragmented, collagist dramaturgy that, as Walter Benjamin noted in his essay ‘What Is Epic Theatre?’ (1931), proceeds in ‘fits and starts’ of scenes, often interrupted by narrations, songs or film clips, rather than allowing an audience to immerse themselves in a linear storyline. fragments follows his career through scrapbooks, sketches, notes and other ephemera, from his emergence during the mid-1920s, superseding Expressionist playwrights such as Georg Kaiser and Ernst Toller, who were prominent after the First World War, to his exile in the US and difficult return, postwar, to what was by then East Germany – Brecht was one of the few Weimar artists to stay alive, working and not disgraced by previous association with the Nazis after the Second World War. The constructive methodology developed by writers, even those as influential as Brecht, often remains the preserve of researchers and aspiring authors. Turning his methodology into an exhibition is a bold undertaking – the only comparable one I can remember is the ICA’s I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker in 2019 that, like fragments, presented scraps of text alongside live performances.

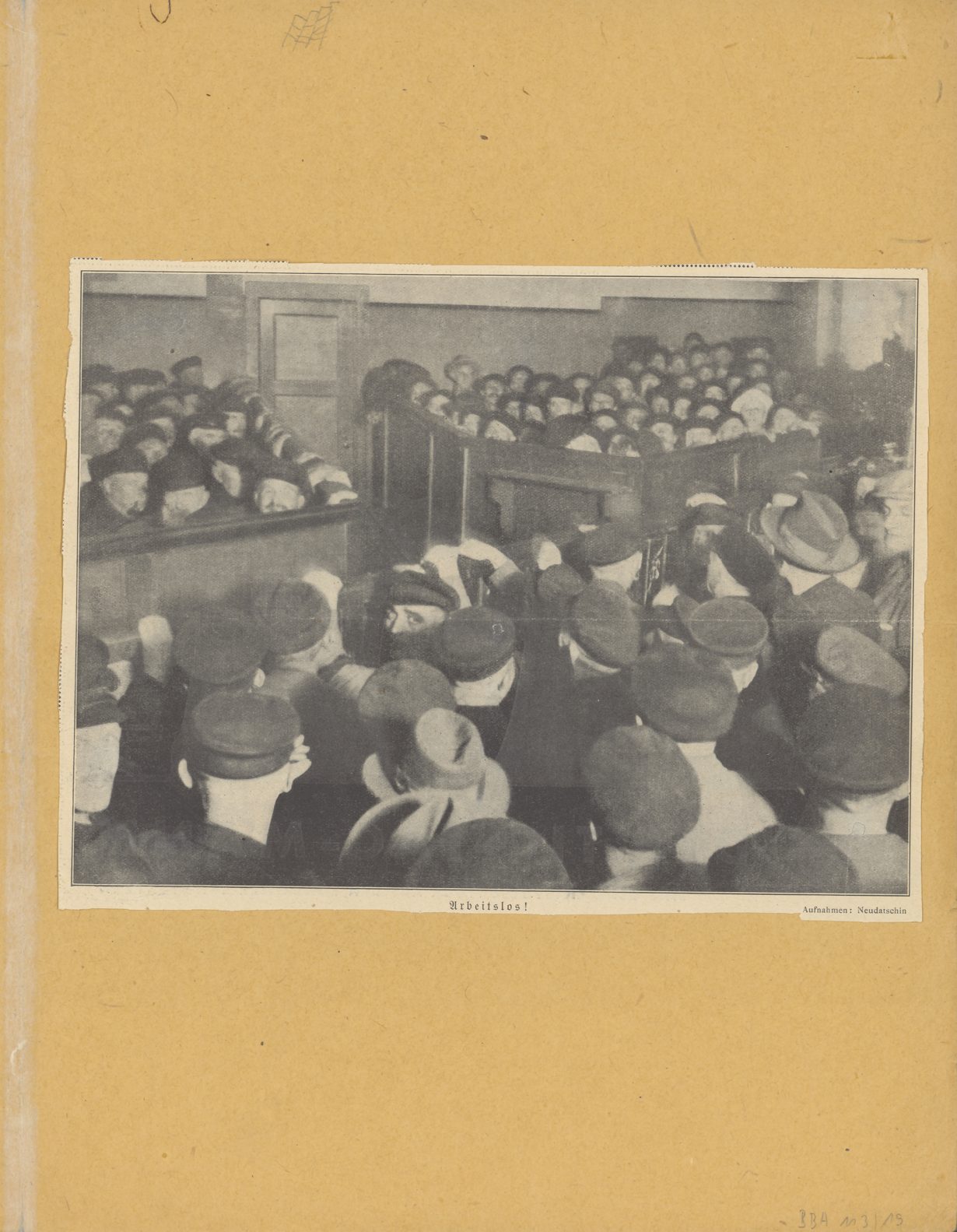

The fragments of his scrapbooks do not mention Expressionism, Dada or Neue Sachlichkeit in any of their forms, and are exclusively focused on politics. These evocative period pieces, along with the notes and sketches he made in writing and staging his works, provide insight into Brecht’s methods. The first room opens with newspaper cuttings that Brecht collected, in several languages, that span the global struggle against fascism and for socialism. Presented in vitrines, these range from a photo of Jews at the grave of a man called Adolf Hittler who died in Bucharest in 1892, to images of Bonnie and Clyde after their deaths, to provide a sense of social tumult away from more obviously political clippings, such as the pictures of Lenin and Stalin or the reports of starvation and war across Europe and in China. On the walls are photographs that Brecht found in newspapers and magazines, annotated with four-line poems – his ‘text-image critique of war under capitalism’, begun in 1944, that became War Primer.

In a side room on the ground floor of Raven Row is a ten-minute extract from Slatan Dudov’s film Kuhle Wampe or: To Whom Does the World Belong? (1932), which Brecht cowrote with Ernst Ottwalt. Here, people on a train have a political argument, prompted by a passenger reading a headline about coffee supply in Brazil being destroyed to keep prices high. Brecht’s intention of using his work to prompt debate among its viewers is unmissably clear: he does not offer an obvious conclusion, but rather pushes his audience to ask questions about the mechanisms behind the economy, rather than just accepting its fluctuations as being unpredictable and impossible to influence.

The other rooms are full of similar photographs, notes and sketches, with the most effective containing script excerpts from Brecht’s famous Nazi allegory, the play The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui (1941) – at points, the intrigue or importance of the archival material has been lost in translation or to time, so an English version of this text is very welcome. As might be expected, the exhibition works best when seen with the accompanying 90-minute performances, designed and directed by curator Phoebe von Held and run twice per day, of sections of four unfinished texts, written during the 1920s. These take place across Raven Row’s three floors, packed into small spaces with consciously amateur cardboard sets and including actors who change costumes and zip across rooms to feature simultaneously in more than one play. These bring a wild vivacity to the archival material: there’s a joyfully am-dram aesthetic to this 90-minute medley that takes its breaking of the fourth wall to extremes as players constantly enter and exit via an open window, capturing the attention of people passing outside the gallery and happening upon an ephemeral form of street theatre.

In a scene from one of these abandoned works, Fatzer: Downfall of an Egoist (1926–30), about a four-man tank crew who desert their station in the First World War, one of the crew opens a door to the foyer where other actors are singing to say, “Can you lot be quiet please? This is my best bit!” The fragments of The Bread Shop (1929–30) carry the most contemporary resonance, being about precarity and homelessness amid the Great Depression. These also have the most concrete characterisation, moving beyond the archetypes (such as the ‘Cashier’ or the ‘Billionaire’ in Georg Kaiser’s plays) of Expressionist drama. This allows some identification with its protagonist, Queck (played by Efé Agwele), in a manner not typical in Brecht’s later work, while the dialogue highlights class conflict, and the role organised religion – in this case the Salvation Army – plays in diffusing class consciousness.

Compared to Brecht’s more famous works, The Bread Shop is not as directed towards a mass audience as The Threepenny Opera, Brecht and Kurt Weill’s 1928 anticapitalist musical reworking of John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera (1728), nor as razor-sharp in presenting a political dilemma as Brecht’s 1939 play Mother Courage and Her Children,about a woman profiteering from the Thirty Years’ War. It’s an interesting period piece, speaking to us from its time of constant crisis to our own, a hundred years later, in a way that is typical of the entire exhibition. None of this is a demand to revive Brecht’s style as he developed it, specific as it was to his context in the 1920s: we can all create our own fragmentary archives of texts and images now, using the internet for this purpose without even thinking too deeply about it, in an all-encompassing media environment that makes it easy to feel like any statements we make, from a throwaway comment to a structured work of art, are ephemeral and inconsequential. Rather, fragments is an invitation to reapply Brecht’s fundamental questions – how can we engage with our present political circumstances, and use our available media as tools, to shake audiences out of a sense of powerlessness, educate them about who oppresses them and reinvest power into artistic practice at a time when the arts are no so much censored as underfunded and ignored?

brecht: fragments at Raven Row, London, through 18 August