Like a cigarette, ‘feelgood’ art is contrary, anachronistic and fleeting in its pleasure

What is your ‘feelgood’ film? A rom-com perhaps, or an action flick? Something that doesn’t require much brainpower, is eminently rewatchable and offers a welcome distraction from the real world. Seasonal romps, superhero blockbusters and endless adaptations dominate cinemas (A Minecraft Movie just broke box-office records), while streaming algorithms line up your old favourites for unlimited repeats. At the end of last year, The Guardian launched ‘My Feelgood Movie’, a weekly series in which writers praise the ‘unmitigated joy’, ‘boundless optimism’ and ‘intense nostalgia’ of their choices, while unremittingly cheery articles everywhere from Vogue to Forbes expound on the power of the feelgood film to ‘bring out the smiles’. Popular culture right now is determined to keep us where we’re content, comfortable, familiar. But when was the last time you heard someone suggest a visit to an art gallery to take your mind off the real world, bound up as it is with the social and political demands of the present? For the last decade, the artists chosen to exhibit in major international biennials and prize exhibitions, from the Venice Biennale to Documenta, the Future Generation Art Prize to Germany’s Preis der Nationalgalerie, are more likely to invoke the politics of identity and their own place within an increasingly divided society than celebrate, say, the unmitigated joys of springtime or a lover’s embrace.

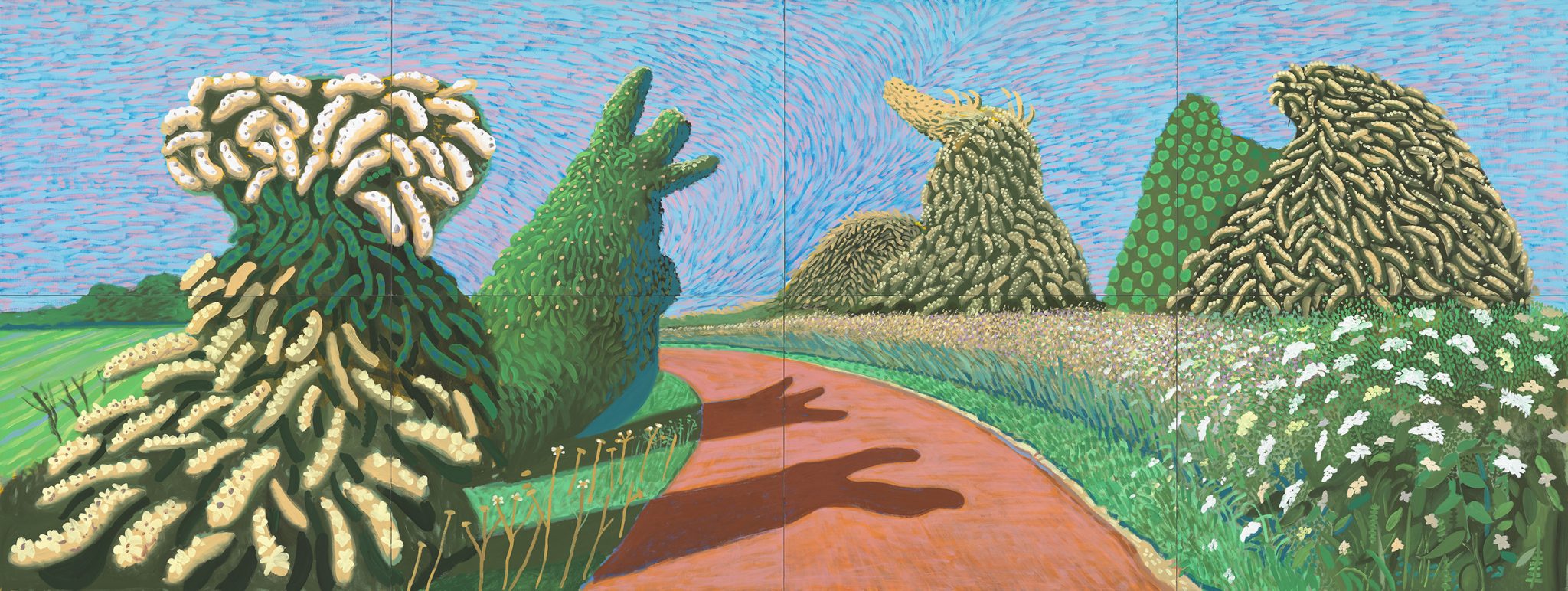

One exception might be David Hockney, who this week opened David Hockney 25 at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris – ‘the most important show of his career’, reckons guest curator Norman Rosenthal, who, if nothing else, can’t be accused of false modesty (but who wants modesty when you’re plugging your own merch). In typically bombastic style, Rosenthal declared Hockney ‘the Picasso of our times’ in a slew of recent interviews as he reflected on both artists’ enduring popularity and their ability to sell tickets. ‘Both really looked, and showed what they saw, and brought joy,’ he said. It is this uncomplicated relationship to his work that perhaps makes Hockney so perennially popular, his fascination with the ebbs and flows of nature a persistent, lyrical refrain across his paintings, photography, 3D scans and his experiments with multicamera video. Even when Hockney has made forays into iPad ‘paintings’ of his local Normandy landscapes, apparently embracing the technology of the new, he has chosen to pay homage to Van Gogh in his impressionistic brushwork, maintaining an age-old Romantic model of the landscape artist.

That impulse to look backwards to simpler times and – crucially – a refusal to look beyond one’s immediate surroundings to interrogate the deeper bubbling inequities of the present moment, offers a blueprint for an escapist version of art that retains the ‘feelgood’ factor. ‘Do remember they can’t cancel the spring’ is written over the entrance to the exhibition, a slogan of optimism Hockney coined during the COVID lockdown of 2020 as he painted in his garden among the first buds and sprouting yellow daffodils, the bright results of which are on abundant display here. Hockney himself, as one reviewer commented, is as reliable as the daffodils he paints, ‘returning at 87 as he did at 82 to show us how beautiful the world is in spite of those who try so hard to ruin it’. Ensconced among the startlingly colourful paintings and photographs of the rolling Los Angeles and Yorkshire hills and Monet’s own Giverny garden, the message is clear: look here; don’t worry about there.

Hockney’s outlook on art, which could be best described as blissful ignorance, was exemplified in last week’s furore around the decision of the Paris Metro to ban the poster advertisements for David Hockney 25, depicting the artist with a crayon in one hand and a cigarette in the other. Hockney, reported to smoke up to a hundred cigarettes a day, has declared the poster ban ‘censorship’, and smoking ‘a symbol of freedom’. Indeed, few artists have advocated so vocally for the mood-enhancing qualities of tobacco; back in 2007, when England’s smoking ban came into effect, Hockney called it ‘the most grotesque piece of social engineering’ and resolutely stated: ‘I smoke for my mental health.’ A small rebellion against the tides of change, it reveals an artist who is all about living in the moment. Feelgood art, too, could be seen as offering the same reprieve from modern life as a cigarette: a fleeting pleasure, a little bit contrarian and increasingly anachronistic.

If feelgood art trades on the warm pull of nostalgia and easy recognition, then the historical art museum is (often quite literally) a gold mine. Unlike contemporary works that exist in the tension of the undecided present, if you go to see the Mona Lisa or Girl with a Pearl Earring, you know what you’re going to get. Works from past centuries offer a pleasant lack of being challenged by what you see. Pieces that will have been provocative or innovative in their time begin to look nice enough as they become institutionalised and just another part of the canon, decontextualised in their ubiquity. And then they become predictable – the ultimate source of any feelgood factor. It is little surprise that the Musée du Louvre remains the most visited art gallery in the world, while the Rijksmuseum’s 2023 Vermeer exhibition had more visitors than any other in its history. Although David Hockney 25 purports to present just the last quarter-century of Hockney’s prolific output, the artist seemingly couldn’t resist including some choice 1960s and early 70s paintings of flat turquoise LA swimming pools, tall palms and squares of green lawn. Think of it like touring musicians playing a few of their greatest hits to keep the crowd happy among the new material, or the favourite album you like to play on repeat. Those tickets won’t sell themselves.

Of course, there are plenty more contemporary artists beyond Hockney who are reluctant to open up the frame to let the more troubling sides of reality in. Just look at the recent proliferation of neo-Abstract Expressionism – by artists such as Jadé Fadojutimi, Oscar Murillo and Cecily Brown – on seemingly continuous display in private galleries (and private homes) around the world. The commercial popularity of these works also suggests the pleasurable friction inherent in the foregrounding of the past and a refusal to innovate with the times, on the part both of the artist and the viewer. While contemporary figurative painting that offers a romanticised vision of intimate moments between its subjects – by the likes of young names like Louis Fratino, Salman Toor, Doron Langberg and Jake Grewal – remains stubbornly present in galleries and institutions alike, showing that you don’t need to go to the Louvre to slip into a cosier view on life.

Feelgood art offers a fortress against the world outside and an opportunity to bathe your brain in the immediacy of the work in front of you. No, it’s not going to inform you about contemporary ‘issues’ of climate change or postcolonialism – and indeed why should it? Just as you wouldn’t watch Ratatouille every day, feelgood art has its place at the lighter end of culture. Like the normcore trend for plain T-shirts and jeans, it doesn’t strive for novelty or difference, and in doing so acts as a refreshing reminder that not everything needs to promote change. Self-indulgent? Perhaps. Liberating? For some. Easy? Certainly. Not unlike the experience of sitting outside in the sun and just watching the clouds roll past, cigarette in hand.