It’s about more than the motions of putting a brush to canvas

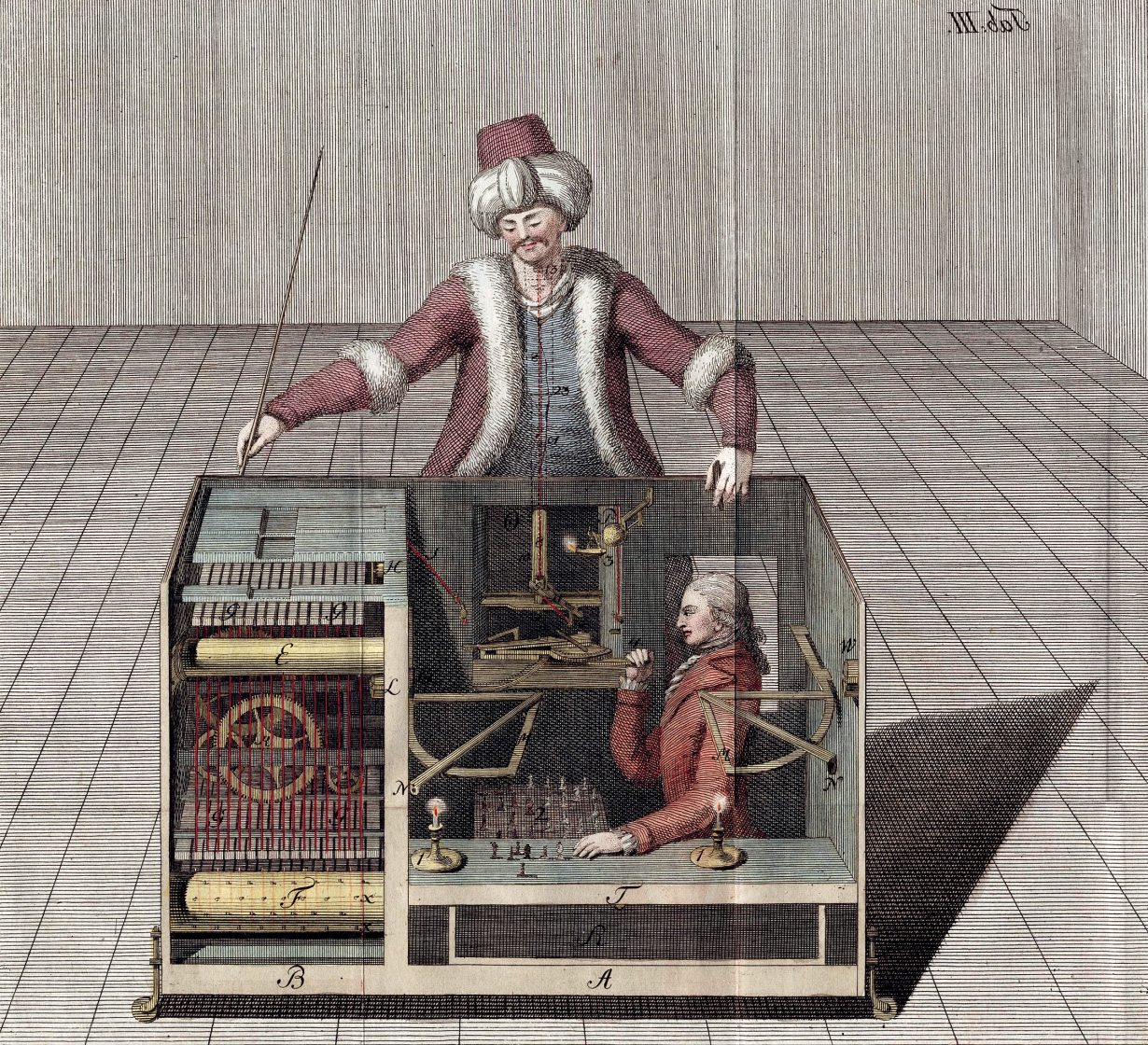

There is this story, which I know at any rate from Walter Benjamin’s Theses on the Philosophy of History (1940), about how in around the Napoleonic era, there was a chess-playing robot that was done up in ‘Turkish attire and with a hookah in its mouth, sat before a chessboard placed on a large table.’ Ostensibly, the ‘Mechanical Turk’, as it was called, was able to ‘respond to every move by a chess player with a countermove that would ensure the winning of the game.’ The robot would tour courts and salons, wowing onlookers with its marvellous mechanics. But it was all just an illusion. Inside the table – made to look transparent, with a system of mirrors, sat ‘a hunchback dwarf – a master at chess,’ who could see the game, and would operate the puppet in response to his opponents. The Mechanical Turk wasn’t ‘really’ doing anything. It was useless – until animated by specifically human skill.

Anyway. The other week, I came across a news story in which a robot, powered by AI, was described as ‘the first robot to paint like an artist.’ The robot in question, it turns out, is nothing new – Ai-Da, ‘named after computer science pioneer Ada Lovelace’ – has been trotted out by creator Aidan ‘no honestly, she’s named after Ada Lovelace’ Meller for years now (ArtReview covered her 2021 appearance at London’s Design Museum, with Imogen West-Knights wondering why the robot had been made to look like ‘a kind of hot woman’ – a vital question IMO).

So why are we still writing about Ai-Da in 2022? (Aside from the fact that there is nothing new under the sun? And that the news is almost exclusively designed around telling us the same old things we’re used to being told every day as if they were novel, an endless cycle of infinite sameness and infinite forgetting, as if ‘no-one was talking about’ any of the supposedly urgent things we’re constantly exposed to, despite the fact that everyone is, all the time and every day? Except also if you asked someone on the bus about them they’d probably have no idea what you were talking about, because we’re all locked by social media in our own little discrete algorithmic bubbles of solipsistic stupidity? Yeah, aside from that…). I think that now the robot is able to use a brush to paint instead of just sketching something and having a human artist fill it in later. Something like that. It made an appearance at the Venice Biennale last week. But none of that is really important.

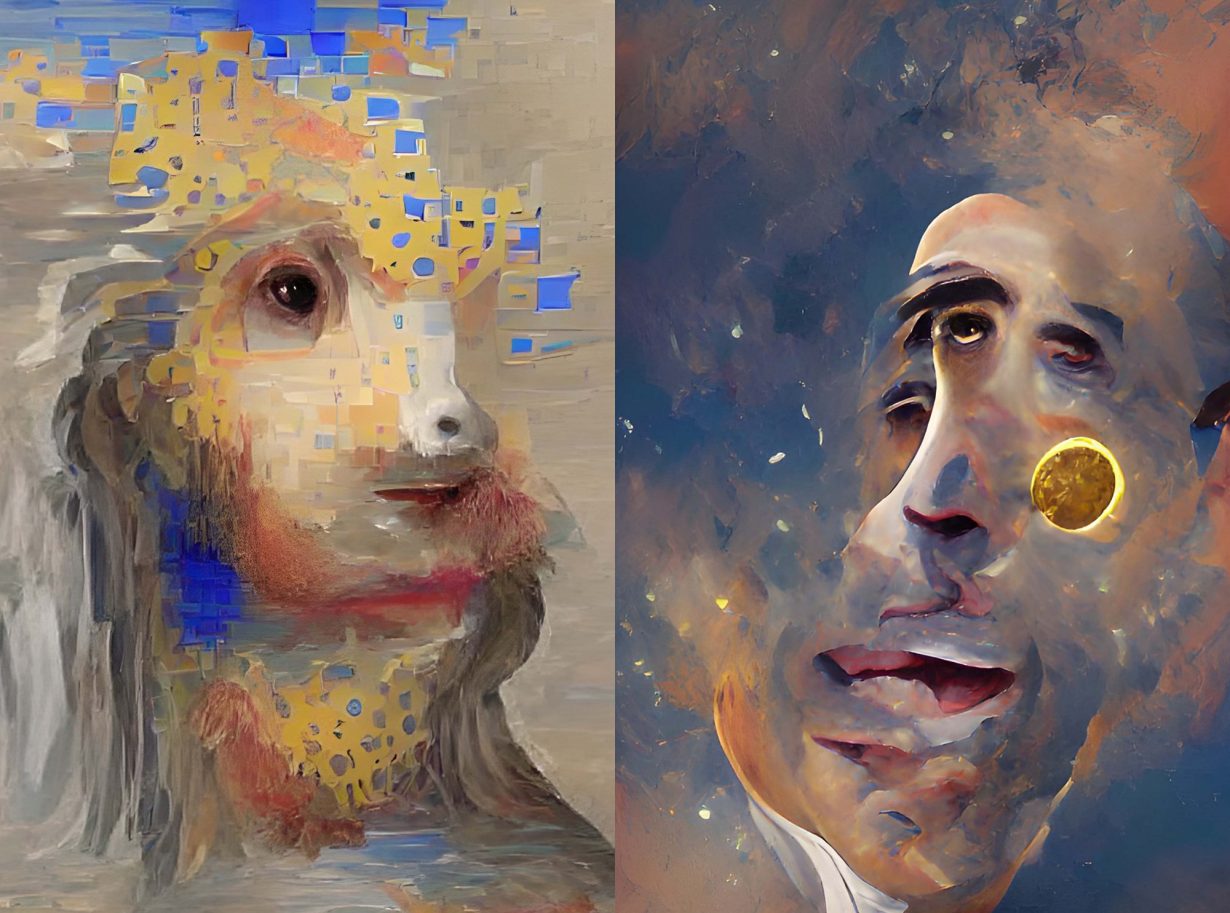

What’s important – and what’s interesting about all this, to me – is this claim, that Ai-Da, no matter how long she’s been in the ‘hey look at this, some AI bullshit’ side of the news game for, is ‘the first robot to paint like an artist.’ What does this even mean? What exactly is it to ‘paint like an artist’? It is not, after all, novel for AIs to be used to generate art: I can fire up a website like the AI art app Wombo and immediately produce a picture of ‘an AI painting like an artist,’ which for some reason gives me something that looks a bit Jar-Jar Binks, or ‘Jerry Seinfeld’s face becomes the Moon.’ Look:

What is it that Ai-Da is supposed to be doing that’s different to this? And why might this difference be thought to place the hot-lady-named-after-her-creator robot closer than the Wombo website to, say, Cézanne? Were no philosophers of art consulted here at all? (Boy, I sure hope someone got fired for that blunder).

Creator Meller claims that Ai-Da is ‘an ethical project,’ which exists as a ‘comment and critique’ on rapid technological change. He has also stated that the question raised is not ‘can robots make art?’ But rather, ‘now that robots can make art, do we humans really want them to?’ In terms of the ‘painting like a painter’ thing, I believe the idea is that Ai-Da can use a brush, and observes her subjects directly, through the cameras which function as her eyes. In this sense she is able to paint ‘like a painter’ directly from a model, or from nature.

But the problem with all this is that it is completely wrong-headed. Of course a robot can be set up to look like it is painting (although to make such a robot does nevertheless require a great deal of engineering skill). But to paint ‘like an artist’ is not simply to go through the motions of putting a brush to canvas.

To understand this, consider another controversy, that I’ve seen people discussing Online. This is something ‘trad art’ lovers like to note for some reason. Hitler was, famously, rejected by the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, paving the way for him to become a fascist dictator. At around the same time, Egon Schiele was accepted by the Academy as a student. But Schiele’s work is marked by an extravagant, intense physicality, most obvious in his frank, exposed nudes: his work is bold, and distinctive, and it is immediately apparent, when viewing it, why he should be perhaps the most celebrated of the Expressionists. Whereas Hitler’s work just, you know, looks like the stuff it’s of. The trad argument is that it’s good for stuff to look like what it’s of, which is why Hitler was a better painter than Schiele. But of course that’s ridiculous: because actually, Schiele’s way of looking at, and presenting, the human body, tells us far more about how reality is – about what we are – than Hitler’s painting of, like, the fact there is a castle there.

Hitler, in short, was a painter. But he did not paint like an artist. Maurice Merleau-Ponty makes a similar point in his wonderful 1945 essay ‘Cézanne’s Doubt’ (which ranges a lot more widely than anything I’m about to report here, and is deeper than anything I’m claiming in this piece, so you should at least click the link and read it as well – if not instead). Cézanne, Merleau-Ponty tells us, always strove to present things as they are. But this meant going beyond the surface of things, while also somehow managing to keep it in view. As Merleau-Ponty writes:

‘[Cézanne] was pursuing reality without giving up the sensuous surface, with no other guide than the immediate impression of nature, without following the contours, with no outline to enclose the colour, with no perspectival or pictorial arrangement […] He did not want to separate the stable things which we see and the shifting way in which they appear. He wanted to depict matter as it takes on form, the birth of order through spontaneous organization. He makes a basic distinction not between “the senses” and “the understanding” but rather between the spontaneous organization of the things we perceive and the human organization of ideas and sciences.’

In other words: in his work, Cézanne was not just presenting us with, say, a landscape, or a picture of his father. He was articulating a philosophy: a view on how things both could, and should, be seen. This is what it is to ‘paint like an artist’: to use paint and canvas to present a way of seeing the world (of course this might not need to have anything to do in particular with how things are ‘objectively’ seen at all – but in Cézanne’s case, it did).

A robot cannot do this – any more than Hitler, in his dull, workmanlike paintings, ever really managed to. In fact, no matter how sophisticated ‘artificial intelligence’ gets, no robot ever will be able to (a robot could be programmed to paint in the style of Cézanne, I’m sure, but it would not have his eye – or his doubt). The notion that some robot might – that AI might somehow ‘evolve’ to be sophisticated enough to allow a robot to ‘really’ think, or to paint – is based on a total misconception of what AI actually is. You might as well expect an iron to evolve to answer phone calls: it’s just not that sort of technology (if an iron did start answering phone calls, it wouldn’t be an iron anymore).

‘Artificial Intelligence’ is the name we use for a novel, sophisticated sort of tool, which is able to analyse and utilise data-sets in ways that are in fact remarkably unlike the human mind (no individual human being can process data at anything approaching AI speeds). But an AI not only needs to be designed by a human engineer – it also needs to be fed the right inputs, in order to spit out anything interesting or comprehensible as its output.

If I use Wombo, to produce a picture of ‘Jesus and the two remaining Beatles eating the sun,’ then the AI is no more creating the picture, than a paintbrush or a canvas would, if I’d chosen to paint a picture of Jesus and the two remaining Beatles eating the sun with that. I am using the AI tool, to make a picture of Jesus and the two remaining Beatles eating the sun.

It’s quicker, sure, than painting on canvas. Although the downside is that it’s also much more subject to random factors beyond my control. Just try entering the same prompt on Wombo yourself – you’re unlikely to get the same picture as me. Arguably the output has more to do with how the engineer has programmed the AI, than what I am putting into it – although I could also, technically, make a painting AI tool myself, to suit my specific purposes, if I wanted. But still: if anyone is, then I am the artist here. I might not have had to do all that much beyond input a string of words – although there’s also plenty of ways that I could edit, and alter, the output I’ve received here later on. But the AI can never be anything other than my tool. In her case, ‘Ai-Da’ is, most charitably, a tool which you are able to use to, say, create a portrait of yourself. Arguably this articulates a way of seeing the world – but it is not that of the robot: it is that of her designer, or her user.

But hey. Back in Napoleonic times, they never would have been able to make a spectacle out of everyone being beaten at chess by just like, Some Guy. In just the same way: tech guys love to hype up the potential of AIs to do far more than they ever reasonably might, because the promise of this expectation makes investors vastly more likely to throw money at them. Mechanical Turks will always proliferate, just so long as there are audiences of rich idiots who don’t really know what’s going on. But don’t be fooled: ‘artificial intelligence’ is always going to need actually-intelligent creatures like us, in order to be able to do anything at all. No robot is, or could be, Paul Cézanne.