It’s time that digital artists up their game

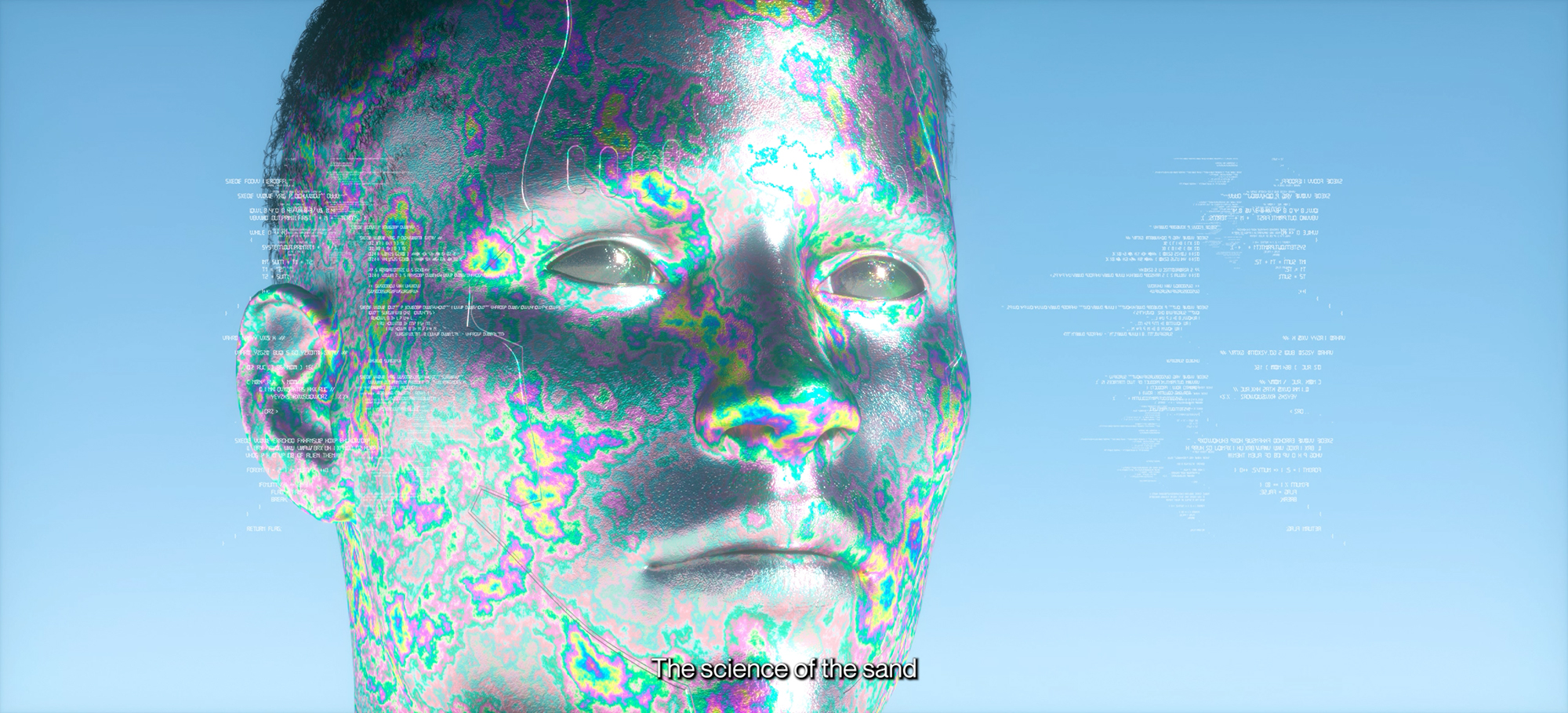

After searching for a new cool in the doldrums of the pandemic, cyberspace’s aesthetes have found a winner in ‘Speculative Futurism’. Top institutions – Serpentine, MoMA, Tate, Centre Pompidou – now look to digital artists for explorations of the future in response to widespread uncertainty over tech’s growing power. Artists draw inspiration from sci-fi and, using powerful graphics chips, game engines and generative AI, birth high-polish worlds filled with futuristic technomagic. Lurking inside are ‘myriad shapes that humanity might take, from robots and cyborgs to haunting, seemingly alien life forms’, as the New Museum puts it in the press release for their upcoming blockbuster exhibition New Humans: Memories of the Future.

I don’t want to be a cyborg or haunting alien; I’m barely scraping by in this human form. I can’t follow artists into the imaginary while real war rages across every sector – military, ideological, economic, symbolic. Yet the speculative futurist, whose subject and medium revolves around the very technology that has transformed society for the worse, is missing in action. Despite these artists’ interest in finding society’s escape hatch, their utopias roll cleanly into their dystopias, each serving as a well-rendered capitulation to unmasked technofascism. Neutralised by a fixation with techno-weaponry disguised as creative toys, digital art’s cinematic universe blasts off from Earth.

The speculative futurist hits escape velocity by invoking the resigned C’est la guerre: ‘That’s war’, or ‘It can’t be helped’. Pierre Huyghe’s Liminal, held at the Punta della Dogana during the 2024 Venice Biennale, takes this logic to its conclusion. In the AI-edited film Camata (2024), robotic arms dance around a human skeleton lying in a featureless desert. Another darkened room screens the eponymous Liminal (2024), in which a nude woman wanders a desolate void, at times curling into the foetal position, her face replaced by a black hole. Huyghe’s exhibition issues many warnings, but instead of scaring me into calling my senator, its theatrical tragedy turns the end of the world into something I’d like to see for myself. Huyghe plays hospice nurse, guiding me to anticipate decay, desire disappearance and submit to death. Last year I experienced that death as relief. Recalling now that the skeleton, once a Chilean miner, is real, while the living woman is simulated, I’m not sure catharsis was a good outcome. I’ve run out of patience for the apocalypse in 4K.

The downfall of humankind feeds one artist’s fears and another’s dreams. Sybil Montet’s video essay Geomancy (2024), which screened at Basel-based HEK’s Mesh Festival last October, indulges in the spectacle of posthuman fantasy. Twinkling cyborgs without pupils smize over a soaring techno track. Pastel nature scenes, pink lens flares and sci-fi visual artefacts decorate an indulgent technologised eco-world. In voiceover, Montet reads off her troubling concept: “Can we disengage from the erosion of the contemporary world and choose not to contemplate the ruins of our future?” (No.) Her planet is pure vibes and an incomplete idea, whose ethics rest on the shoulders of terraforming cyberwitches who plug AI into holographic snakes. She makes a promethean bargain for maximal technological interventionism by trading away the rights to our humanity. It’s a bad deal made worse by its tacit endorsement of the Baron Harkonnen of Silicon Valley, Marc Andreessen, whose ‘Techno-Optimist Manifesto’ (2023) calls for the very same thing, while naming ‘enemies’ that include ‘social responsibility’ and ‘tech ethics’. So it goes.

Critic Ben Davis, in his prescient book Art in the After-Culture (2022), calls these images of the future ‘bad utopia’: false-positive visions that normalise defeat and fold neatly into the propaganda of accelerationist billionaires. It’s the next booby trap in a long-running stalemate over how art can meet the moment. Curators like to frame speculative futurism as productive, but when the art makes utopia blasé and dystopia desirable, there’s a problem with the formula. Artists should study their source material. Novels by Ursula K. Le Guin, Octavia Butler and Philip K. Dick are profound narratives of struggle, allegories for real wars and atrocities, and negotiations of ethical dilemma and ideological contradictions. It’s not just a problem of story, but architecture. The work of contemporary digital artists has everything to do with present-day power and domination. It requires building ‘a reality you can believe in: one that promises to bring about habitable structure from the potential of chaos’, writes artist Ian Cheng. Invoked by artists without conviction, and who decline to name their own ‘enemies’, speculative futurism devolves into a death cult wrapped in pastiche.

On the other side of the highfalutin boom in speculative futurism is a coming bust that last took down postinternet art. Digital art’s yo-yoing status is a symptom of its umbilical attachment to technological innovation. Its artists only get called up at the height of conflict with new tech, just before the airlock seals us in with ever more mundane evil. Together they hit the culture hard and fast, dazzling us with possibility. Before long we all go numb. So go tech’s blitzkrieg-style shock tactics, invented by the Nazis and restyled by LinkedIn cofounder Reid Hoffman into corporate ‘Blitzscaling’. This was the story of Web 1.0 and Instagram. Soon it’ll be the story of AI. The truth is that digital art was built on a missile silo all along.

Here’s another pretty cyborg fantasy: Marie Antoinette After the Singularity #1 (2024), by Grimes, Mac Boucher, Mariya Jacobo and Eurypheus, an AI-generated tapestry depicting a cybernetic rococo queen. In her postapocalyptic regalia, Marie Antoinette sneers at the viewer in a suit of mechanised armour, while a globe adorns her spikey throne. The upcycled rococo evokes the decadent, accelerationist ideology of ‘abundance’ promised by OpenAI’s Sam Altman. It’s propaganda for an empire whose aim is global technological domination. Grimes claims that AI art ‘has instigated a populist uprising against a symbolic aesthetic excess that’s much easier to demonize than the mundane bureaucratic corruption that’s actually to blame for the failings of late stage empire’. It’s the same busted excuse given for hollowing out American cultural institutions. Perhaps she’s forgotten how Marie Antoinette’s story ends.

Walter Benjamin wrote that ‘all efforts to render politics aesthetic culminate in one thing: war.’ What the future looks like is now all-out propaganda battle. Its lynchpin is digital territory and all the people who make their lives in it. Digital artists need to raise the bar, whether they openly enter the fray or not. They’ll never transcend their karmic cycle until they can resolve the terminal contradiction at the heart of the practice. But rather than damning digital art, this is exactly what makes it so interesting. Contradiction works as a catalyst for change from within a corrupt system, not to mention a powerful narrative device. Working through the contradiction, instead of ignoring it, holds the keys to an avant-garde.

Kat Kitay is a writer based in New York

From the May 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.