The kids at Imperial College protesting an ‘inappropriate’ Gormley sculpture miss how art can make the prosaic that little bit stranger

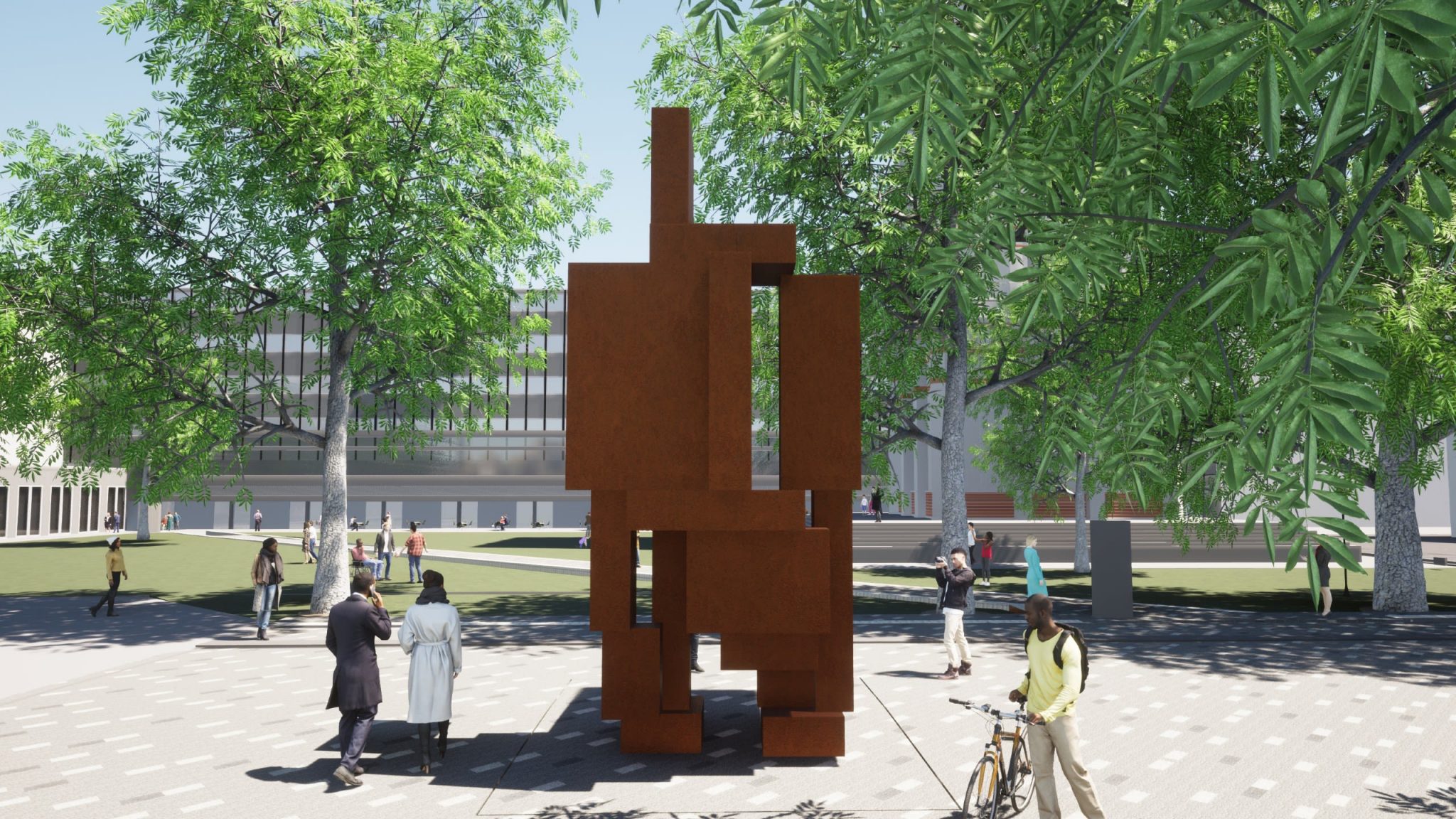

The other day, news broke that Antony Gormley had been given provisional permission by whoever runs Imperial College London to erect a big statue that looks like a guy with a lob on outside the university’s ‘newly built Dangoor Plaza’ (no prizes for guessing what the surname of the person who gave them the money to build that is). The students’ union, of all people, are protesting, claiming that having a dick statue may ‘hurt the image and reputation of the college’ – as if anyone would ever have heard of Cerne Abbas without the giant (are the kids OK, incidentally? Who are these nerds? I would have given anything, when I was at university, for the authorities to have accidentally erected a dick statue).

Still more beautifully, Gormley himself has taken time out from stealing other people’s bins to insist that the statue, which is very obviously of a guy with a big erection, is in fact of a ‘squatting human figure’ – providing an explanation in which he has seemingly very pointedly managed to include the word ‘balls’.

‘Through the conversion of anatomy into an architectural construction I want to reassess the relation between body and space. Balancing on the balls of the feet while squatting on its haunches and surveying the world around it the attitude of the sculpture is alive, alert and awake.’

The guy who donated the statue, meanwhile, alumnus Brahmal Vasudevan (he’s a venture capitalist), has claimed he shares Imperial’s ‘vision for a vibrant public space,’ and said he was ‘proud to bring this iconic, world-class piece of art’ to its campus.

What is public art today, other than statues which are probably if not 100 percent certainly of dicks? Recently, I began browsing ArtUK’s newly-launched database of all the public art in the UK: a plausibly exhaustive record of all the random statues and abstract sculptures plonked in British public space – in parks, universities, outside shopping centres and churches, by the side of the road…

One sees things in it one never would have expected to, like a sign telling everyone that they’re now in ‘Market Drayton, Home of Gingerbread’, or a shrine to Minerva from the 2nd century CE, or just like, some gates. I felt a sort of mounting Borgesian vertigo. How did they decide what ‘art’ was, for the purposes of the archive? How did they get all the pictures of it? Were they just… were they just taking pictures of everything? Am I there? Is this sky, that leaf, this moment?

It’s interesting, exploring the whole great hyperobject of it all. Browsing the collection, your eyes are turned to the unnoticed corners of the city: things one passes every day, but never recognised or even quite realised they were supposed to be art. Divorced from their real, public context, they seem different – like when you’re not quite sure whether or not someone on the tube platform went to your school.

As a result perhaps, the best pieces to discover are not the genuinely spectacular ones (Gormley’s Angel of the North, for instance), but precisely those which disclose some stretch of public ‘space’ you never would have otherwise imagined was there. A 1966 figure of ‘a woman with a basket on her head containing chickens’ stands outside a closed flat-roof pub in Wallsend, overgrown with weeds: a memorial to its own inability to sustain the space it was supposed to help create. A bandstand just outside of Newcastle city centre lies vandalised in what I know is semi-wilderness, its higher possibilities exposed by its presence here (I had always thought it was supposed to be a climbing frame).

Experiencing public art like this, one never quite has the real thing: the database extracts from the place, which must then be imagined back into it – perhaps based on experience, perhaps not. In a way, the database is an impressive act of preservation – but if any of these pieces were destroyed, some knowledge of them would, still, have been irreparably lost.

The point of public art, after all, is not for any given piece simply to stand, as if it might be the same had it been placed anywhere, but to stand specifically there, where it is. This is part of why when one sees, for instance, the Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, the whole spectacle is so horrifying, everything feels so close and loud and you’re unable to breathe: the museological equivalent of seeing an animal going mad with boredom in a zoo. Public art is not so much there to look beautiful, as it is to allow the space it stands in to function through it: like The Dude’s rug, a good piece of public art really ties the place together.

Which could also mean disrupting it, or calling it into question: a Barbara Hepworth hanging above a Wagamama’s in Cheltenham, for instance, or a Rodin outside a Nando’s in Harlow, make the prosaic that little bit stranger, lend the drably immanent some friction with the transcendent: the sort of thing anyone really needs to live. The same goes for the Imperial College dick: transforming a drab alumni-financed bit of newbuild campus space into something much more ridiculous and fun than its erectors can ever possibly have intended (this also, incidentally, is why Imperial’s dully serious students are wrong to want to remove it).

One thing that surprised me, browsing the database, was that public art still very much continues to be installed. Narrowing my search down by date, I honestly assumed that little had been put up in the past decade or so, especially not (beyond controversial phallic pieces) since the pandemic, but I was happy to be proved wrong. A big weird statue of a woman in the middle of Woking, a mural to the Derry Girls in Derry, a statue of Greta Thunberg that someone has erected in, of all places, Winchester.

My natural instinct is to think that public art is the sort of thing the Tories would like to purge, that their idea of a perfect street is some grim blank, a dual carriageway running through what used to be a city centre, with great skyscrapers of new build offices, all either empty or being hastily converted into shoddy ‘studio living pods’, running alongside it. But the fact is that the powers-that-be have made more headlines recently trying to preserve it: with statues of various lauded ghouls and other ‘controversial’ historical figures being handed their very own presidential-level security details ever since the statue of slave trader Edward Colston that used to stand in the middle of Bristol went ‘plop’.

Search ‘Edward Colston’ on the public art database now, and one sees what remains of it: the empty plinth. It is a much better piece of art now – and not just because it depicts the absence of a slave trader. The empty Colston plinth stands as a monument to the action of dumping the statue in the water: the rising up of the public against it. Here then, public art does not just create public space: through the work of the public upon it, it has become expressive of the civic identity any public art ought ideally to facilitate. The judgement on Colston has been cast: he is in the water now (or, actually – he’s in a museum, but spiritually, he remains forever dumped in the water).

Newspapers act outraged when angry crowds righteously vandalise statues of old Empire villains; a lot of public art is itself accompanied by signs telling you not to touch it nor climb it (an injunction I am already on the record as despising). None of this is true to the spirit of what, really, public art ought to be – which is actually maybe something closer to ‘street art’, except not by Banksy: something radically and anarchically democratic. Public art can never exist as ‘art’ that is ‘public’, unless the public are themselves given sufficient freedom to interact with it. A statue of a lion in a park is not really ‘public art’: a statue of a lion which has children swarming about it and roaring is.

The best public art is for playing with, for clambering over, for laughing at, for being in, or alongside. And sometimes, of course, it is for destroying. Scrolling through the database offers a window into this utopia of public art. A world where the public can not only take away art at will, but install it too: erect monuments to whatever they please; abstract sculptures that tie the space together in whatever way they like. If public art were truly ours, then we could all be its authors.