The Mexico City museum’s display of works by Gallardo caused a storm in the city’s art scene. The aftermath told us all we need to know about art and censorship today

Ana Gallardo’s touring anthology exhibition Tembló acá un delirio opened at MUAC Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City, on 10 August. The Argentinian artist has been a constant presence in the city since her arrival over a decade ago, and her efforts to provide residencies and studio spaces for incoming artists from her home city have been an important community-builder for Buenos Aires–Mexico City relationships. Yet the response to the show was, by and large, muted. That all changed on 9 October when Casa Xochiquetzal, a shelter for elderly sex workers located in the Centro neighbourhood of Mexico City, published an open letter to MUAC. In it, they explained why they took offence to two pieces exhibited together in the show: Extracto para un fracasado proyecto (Excerpt for a Failed Project, 2011-2024) and Sin título (Untitled, 2011).

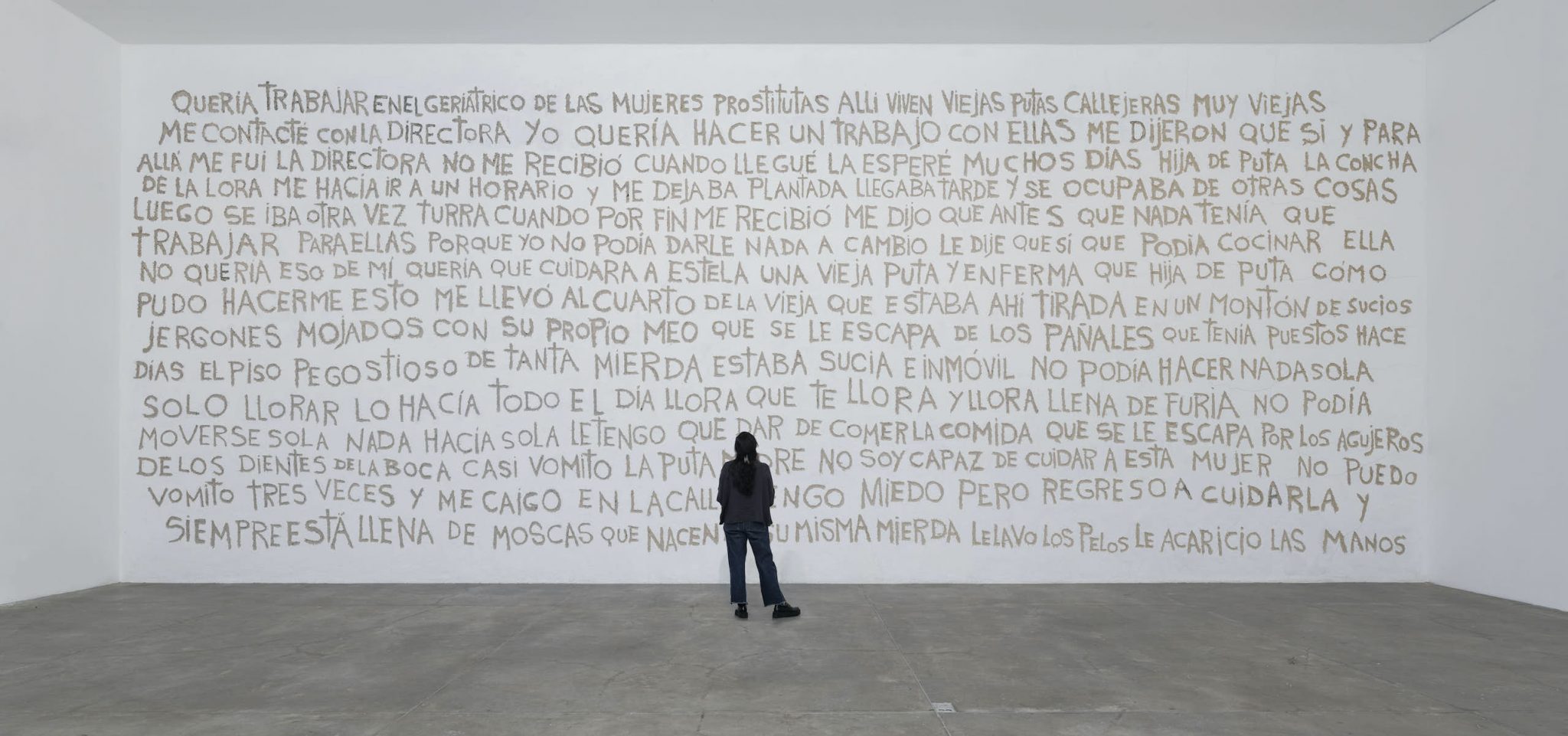

The works are damning for everybody involved. The former is a mural of around 300 stream-of-consciousness words in crude carving onto the gallery wall that narrates Gallardo’s feelings after she approached the shelter about a potential, state-grant funded project back in 2011. In the first two lines Gallardo calls the home’s inhabitants ‘old street whores’. She sounds indignant when asked to do some labour in exchange for access: ‘how could she do this to me … caring for Estela an old sick whore[,] what a hija de puta [a common Argentinian expletive, like ‘son of a bitch’ but more “daughter of a whore”]’. Gallardo describes the woman’s state as ‘laying down in her own piss leaking from her diaper she has been wearing for days the floor is sticky with shit she is dirty cannot move can’t do anything but cry and cry full of fury’. She recounts overcoming her own vehement disgust and fear, writing: ‘I almost puke fucking shit I cannot take care of this woman I can’t I puke three times I fall down on the street I am scared but I come back to care for her she is always covered in flies borne from her own shit I clean her hair I caress her hands’.

The mural references the form of the ‘escrache’, the public denouncement of a person, usually a public figure or someone who has abused their power, and involves graffitiing their home, car, or local neighbourhood. Yet in a crucial difference, Gallardo’s rendition chooses to focus on an entirely disempowered group. Projected next to it is Sin título, a short, clandestine video, shot without the permission of its subject, in which Gallardo’s hands emphatically rub another woman’s as they sit somewhere outside. In one continuous shot, tightly framed from a camera likely attached to Gallardo’s chest, the woman’s face is carefully cut out: we see only a section of her chin and her limp hand between each of Gallardo’s. It’s unsettling to watch Gallardo give a hand massage to someone immobilised after suffering a number of strokes, and therefore with little ability to consent to Gallardo’s action. There’s also something performative about the video’s reenactment of self-redemption.

The women who work at Casa Xochiquetzal to provide shelter, medication and meals to a group of largely dispossessed individuals were naturally offended by the language Gallardo wielded – words long used to victimise and ostracise women sex workers. They also took issue with Gallardo’s violation of their privacy: they claim that other artists and documentarians have always sought permission to work with them, and have protected the identities of residents. That the video does not reveal its subject’s face is itself implicit confirmation that Gallardo understood the boundaries she was crossing. Worse yet is Gallardo’s abject portrayal of the conditions at Xochiquetzal, which its workers altogether dispute the accuracy of.

MUAC’s response was slow, then clumsy: first, on 11 October, with a communiqué that essentially repeated facts about the piece and reiterated the museum’s commitment to ‘the right to freedom of expression and thought, in the terms established by the Mexican Constitution and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights’. They then blocked access to the offending works and ultimately, after a choppy weekend in which the façade of the museum was graffitied with ‘blankkka privilegiada’ [‘white privilege’, but with added Ks], ‘violence is not art’ and ‘total respect for sex work’, shut down the entire show for a day. That evening, on 15 October, MUAC published another press release: ‘In an extraordinary session of their Curatorial and Programming Committee’, they had agreed to remove the two offending pieces; ‘after careful evaluation of the ensuing debates, and dialogue with representatives from Casa Xochiquetzal’, the curatorial team now recognized their significant mistake and ‘offered an apology to the aggravated parties’, citing Gallardo’s agreement with the move. A ‘public forum’ is to be held ‘at some point in the future’. And so the next day the exhibition reopened: they had walled off the door to the contentious gallery and placed a chair in front of it.

In the weeks since, public opinion – mostly espoused on Instagram, X and some of the art press – has become a maelstrom of extreme opinions. On one side: the hardcore identity politics camp, who edify subjects into protected classes standing beyond reproach – in this case, sex-work activist collectives, terminally-online feminists and others thirsty for outrage. On the other: the anti-cancel-culture fundamentalists, quickly warping criticism into trolling, abuse, violence and censorship. At this exhausted moment in social media culture, both perspectives are devoid of nuance and puffed up by a touch of self-righteous narcissism.

That the jittery hand of the institution decided to withdraw its own provocation should not be read as ‘censorship’. Instead it reflects the abandonment of their duty of mediation between the afflicted party and the artist, and goes counter to MUAC’s own positioning as a progressive and open forum for debate, funded as it is by Mexico City’s largest public university and located in their grounds. Put simply: if MUAC anticipated an adverse response, then they ought to let the work stand on its public trial. If they failed to see this coming, then boarding the work up only serves to draw greater attention to their institutional neglect. A museum owes its audience the obligation to properly mediate the information they exhibit, as well as facilitating the space for them to make up their own mind.

The mural is certainly potent in its revolt at the rebuke of one’s entitlement, at the idea of caring for the ailing body of another human being. Is it vulnerable? Sure. Could it be read as cathartic, and in that sense poetic? Arguably. Is it good because it ‘got us talking’? So-called dialogue and attention seem to be the cheap currencies of today’s artworld. Is it also deliberately insulting and defamatory of a very precarious, poorly-funded infrastructure women created to protect each other? Entirely. Many of those defending Gallardo in the heated debate lament the end of an era where artists could act as sociologists and ethnographers within communities they had no connection to, while lacking the rigour, training and careful ethics required. They pine after a time where the artworld had little incidence in the real one; meanwhile communities are pushing back on being taken advantage of in the name of art and museums are not properly equipped to deal with the growing schism between the two. A lack of self-criticality will only hinder effective strategies as the world moves into more complex crises.

Those who want art to shock or provoke remain in favour only when it fits their own definition of society’s ills. What has changed, then, is not the mechanics and systems of artworld institutions and the works they platform, but the dissolution of the fallacy of one audience united by ‘universal’ principles of what and who art is for. That institutions like MUAC failed to recognise this points to an ominous future. If this is how they reacted to friendly fire, it’s hard to tell how they’ll respond to whatever the global conservative turn brings next.

Gaby Cepeda is a writer, critic and researcher living in Mexico City