The struggle to explain an art that looks like it belongs to a globalised, homogenised creative language and yet was created entirely without knowledge of its existence

In the beginning was the word – or should that be the image? This question hangs in the air in Burmese artist Po Po’s slow burn of an exhibition, Primeval Codes, at Yavuz Gallery in Singapore. Comprising a body of paintings sketched during 1986–88 but realised only this year, the works depict simple geometric forms in austere compositions and a red-and-black palette. They are, we are told by the wall text, inspired by third- to thirteenth-century scripts from Pyu, Bagan, Inwa and Pinya that influenced the Burmese alphabet, as well as by contemporary traffic signs. This unexpected combination of influences has been distilled to a vocabulary of squares, rectangles and triangles, whose meanings remain open. That is, until you get to the titles.

Two right-facing triangles stacked one over the other: Fertility. A black square divided into four by red lines: Partnership. At first the titles sound arbitrary, but after some time with the works, a weird thing happens: I start to agree with them. Not through any logical deductive process, but rather through cumulative exposure. For example, a red bar bisecting a black square vertically is titled Freeze. This makes sense: verticals are decisive, solid, unmoving. When a red bar bisects a black square diagonally the title is Wholeness. This is unexpected, but again, perfectly reasonable. This diagonal, or slash, represents divisions or fractions. Here, there is no numerator and denominator, just a division sign with nothing to divide – an elegant way to imply an empty sort of wholeness.

How are these meanings generated? It could be that the images also echo other signs, and the titles pinpoint one of these associations. But it could equally be that these paintings are inherently neutral, and that the titles call their meanings into existence. Or there could be a third way: the series creates meaning in both directions – image influencing title influencing image – in a mutually reinforcing feed-back loop.

These works, which explore semiotics in such a playful and confident manner, were conceptualised when Myanmar was ruled by a military junta and largely isolated from the rest of the world. Since the late 1970s, Po Po has created a diverse body of work including paintings, sculptures, installations and performances whose subject matter is a hard-to-summarise mix of Buddhist philosophy, sociopolitical commentary and whatever he happened to be into (such as the ancient languages in Primeval Codes). Because of the state’s strict isolationist policy, it was not until the late 1990s, when the borders began to loosen and Burmese artists started exhibiting abroad, that he became more widely known.

A common refrain about Po Po’s work, especially among viewers from outside Myanmar, is to say how remarkable it is that it feels familiarly contemporary (at least in the ‘global’, or rather Euro-American, sense), although a large part of it was made with almost no knowledge of such trends or art vocabularies. This judgement is (inadvertently) patronising, because it assumes that the adoption of a recognisably ‘conceptual’ practice signifies an arrival of sorts for an artist. Even the most well-intentioned attempts to connect Po Po to an international context have resulted in awkward moments, like the inclusion of Red Cube (1986) in the National Gallery Singapore’s ‘blockbuster’ Minimalism: Light. Space. Object. exhibition in 2018. Made when the artist was in his late twenties and featuring a rectangular canvas tilted at an angle, below which is a pile of rocks, Red Cube could, in formal terms, pass as one of the geometric works that dominated the rest of the survey show. The problem is, Po Po had never heard of Minimalism when he made it. Over the years, he has said different things about how this work was made to different people. The story he tells ArtReview Asia, via email, is that he had been experimenting with different shapes for canvases and ways of hanging them. At the same time, he also had some granite stones in his studio that he had been stacking into a pile, a practice informed by that of Buddhist monks who, meditating in the jungle, would use such techniques to focus the mind. One day, he noticed he had positioned the mound of rocks right under the slanted painting, and Red Cube was born.

Calling Po Po a minimalist, then, might be construed as a heroic embracing of the ‘intentional fallacy’. But it is also a wilful erasure of the circumstances and thought processes behind the work, which are far from the common reference points of a more homogeneous and globalised artworld.

The fact is, Po Po developed his art in a culture that has faced about 60 years of political struggle, isolation and censorship. The national religion, Buddhism, is an abiding influence in his work, and a lot of what looks like cerebral, contentless abstraction (as in Red Cube) is – as explored below – in reality a literal translation of Buddhist precepts and practices.

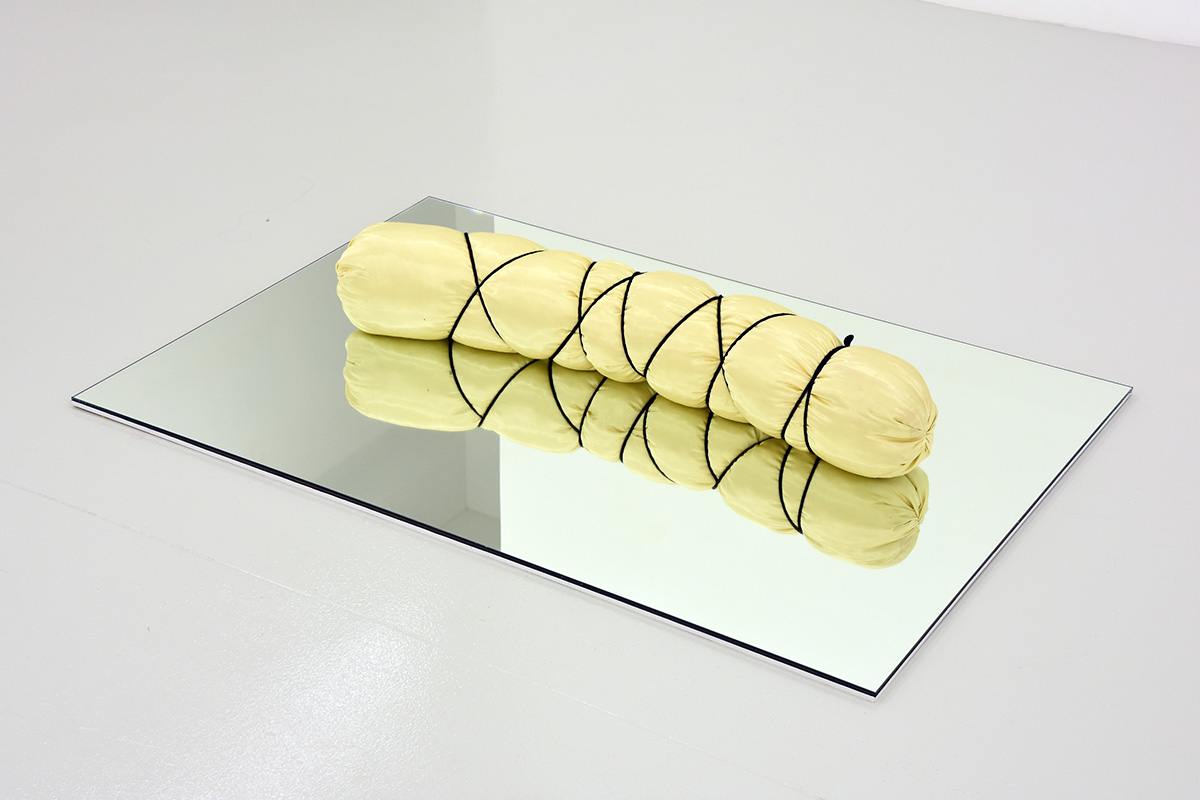

The most extraordinary thing about his work, though, isn’t just his environment: it’s the man himself. A scholar-artist, Po Po ponders aesthetic-philosophical problems seriously and deeply, and solves them for himself. A year after his first solo show, in Yangon in 1987, where he presented abstract geometric paintings, he declared painting dead in interviews, seeing no difference between prehistoric cave paintings and modern ones on canvas. In information-starved Myanmar, he imbibed whatever scrap of foreign knowledge he came across and spat it out in his art in weird and wonderful ways: in that first solo show, for example, his representations of Greek gods (a response to what he read in stray texts that were floating around) as undifferentiated tubes of cloth stuffed with cotton, seem gleefully opposed to the hardness, realism and idealism of classical marble sculptures. Narcissus (1987), inspired by the myth of a beautiful young man in love with himself, is a silk bolster tied by crisscrossing rope, lying on top of a mirror laid on the ground. Evoking both a tied sausage and a limp phallus, the work oozes a defeated, blocked sexuality: self-obsession as bondage and impotence.

and Yavuz Gallery, Singapore

Born in 1957 in Pathein, a rice-producing region in Southwest Myanmar, Po Po had a talent for drawing at a young age. The sum of his formal art education, however, was in attending summer art classes run by the Ministry of Education in high school, where he learned about perspective and composition. In 1979 he graduated from Pathein College (now Pathein University) with a degree in botany, and a year later moved to the capital city, Yangon, where he worked as an illustrator and graphic designer while practising as an artist.

That first solo show, featuring six soft sculptures and 31 abstract geometric paintings, sealed his reputation as the ‘bad boy’ of Burmese art in a scene that mainly favoured realism. The soft sculptures included the Greek-inspired series, as well as others that openly explored sex, such as the pair of gently intertwining bolsters, Erotic (1982–86). Of the paintings on show, the most well-known are the quartet Tejo, Vayo, Pathavi, Apo (1985), inspired by the four elements of the universe in Buddhism: Tejo (kinetic energy, or fire), Vayo (fluidity; water), Pathavi (solidity; earth) and Apo (movement; wind). These forces of nature were here translated into a triangle, circle, square and semicircle respectively, each with gradated combinations of colours that glow and pulse. Like luminous visions from deep meditation, they somehow manage to be universal yet totally idiosyncratic.

A year after his Yangon show, Myanmar was thrown into crisis. In 1988 a series of nationwide protests against the junta’s botched handling of the economy culminated in bloody confrontations that left thousands dead. Po Po, who was also involved in the demonstrations, became disillusioned with art. He chose to go on a ten-year hiatus where he only sketched out his ideas but did not realise any projects. (This is why his works often have two dates attributed to them – one for when they existed only as ideas, another for when they were realised as physical entities.) In 1997 he opened his second show, Solidconcepts, consisting of installations of cardboard boxes, mirrors and wooden crates that reflect his newfound interest in different materials. Significant works from this show include Controlled Tejo, Controlled Vayo, Controlled Pathavi and Controlled Apo (1991–97), which encased the four elements in wooden crates. Fluorescent light tubes stood in for fire, rubber for water, bricks for earth, and a chunk of ice – melting over the course of the exhibition – for wind.

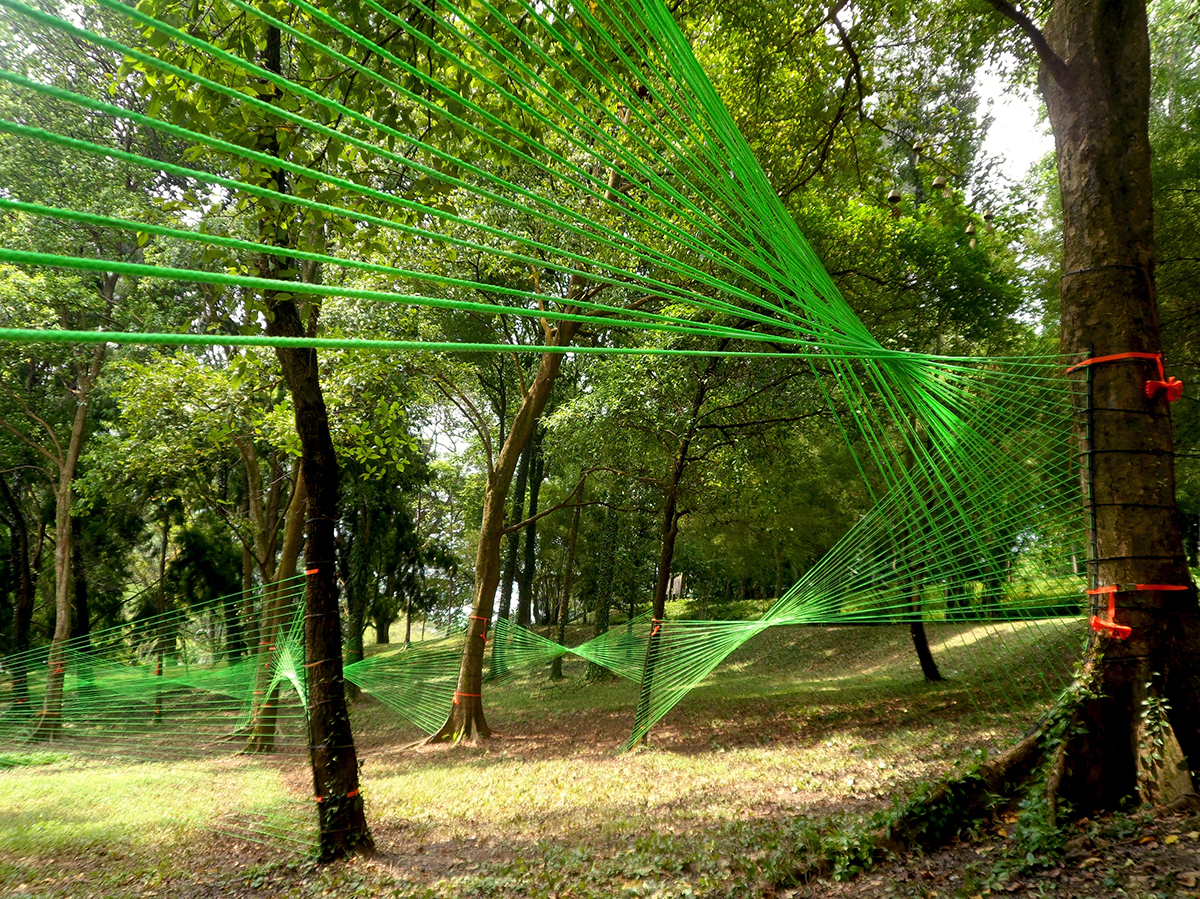

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, he started making ambitious outdoor, site-specific installations in nature, further exploring and dramatising Buddhist concepts. Negative Space #8 (2007) comprised two huge sheets of red cloth hung across two walls in the ancient city of Sri Ksetra, one suspended in the air and the other at ground level. This work, which refers to the traditional canopy above ancient Buddha statues in Myanmar, is documented with the sheets rippling powerfully. Stretched out across the ruins of a fallen empire, holding nothing but wind, it suggests both the ephemerality of civilisation and the nature of emptiness in Buddhist thought. In Road to Nirvana (1993–2013), commissioned by the 2013 edition of the Singapore Biennale, a path is demarcated in the forest by a crisscrossing pattern of green strings tied across tree trunks, forming a web that visualises the interconnectedness of living things.

Because of his limited output and the long gaps between his exhibitions, Po Po does not consider himself a successful artist. But as of late a second wind is blowing. Old works are resurfacing; unrealised ideas being realised. In 2017, after his wife posted pictures on Facebook of autokinetic paintings he did during the 1990s, the response was sufficiently encouraging for him to stage a show of them in Yangon. The process of throwing these black brushstrokes on Shan paper (which is made from the bark of the mulberry tree) was, he told a Burmese newspaper, like ‘riding a wild bull’. His representation by Yavuz Gallery in Singapore has also yielded two solo shows: Out of Myth, Onto_Logical (2015), showcasing works made from 1982 to 1997, and Primeval Codes.

The gallerist at Yavuz shared a titbit. Red and black, he explained, were sensitive colours in Myanmar because of the quirks of the censorship board under the junta. It frowned upon white and black for the contrasting images of goodness and evil they represented, and red for its association with revolution (and after 1988, its link with Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy). Abstraction was also viewed with suspicion, because it could smuggle in political criticism or foreign influence. Had Po Po made these works in 1988, they might not have gone down so well at home.

In this respect, Po Po’s works have an element of resistance. This opens up another dimension in his interest in codes: that communicating in secret signs and systems might be a necessary condition of artmaking in Myanmar, where speaking truth to power could get you tortured or thrown into jail. This may explain titles, such as Leader and Justice, Hardship, Warrior, Defence and Provocative, that allude to political struggle. But unlike the more obvious activism of some of his compatriots, whose banned works have messages hidden in the canvases, Po Po’s works are not ciphers that can be cracked. His is a more slippery tongue.

Meaning flickers in and out of focus in Primeval Codes. Under close attention, certain patterns seem to emerge, and yet, when I try to pin them down, recede. Left-facing triangles tend to be aggressive (Provocative; Warrior), and tall rectangles imply some form of blockage or stoppage (Constraint; Defence; Encounter of Death), but these are vague tendencies, not hard and fast rules. The eclectic symbology suggests a system without fossilising into one. If Po Po has an unreleased painting from this series in the storeroom, and the title were hidden from me, I wouldn’t be able to guess it.

But I get the sense that Po Po is not playing intellectual games with semiotics. The titles tell us he means business. What he is taking on, unironically, unabashedly, are the Big Questions: God (two squarish oblongs stacked lengthwise over breadthwise; a fat cross); Need (two horizontal bars across a square, slightly staggered, not meeting); and Encounter of Death (a black vertical plank with a square face on top; a geometric sarcophagus).

Every encounter with an artist of consequence, in a sense, involves learning a new language. Driven by a fiercely personal logic, shaped by his environment but irreducible to it, absorbing outside influences and then mutating them, and passing through minimalist, conceptual or otherwise contemporary art without having heard of them at the moment of creation, Po Po’s language is communicative without being completely legible.

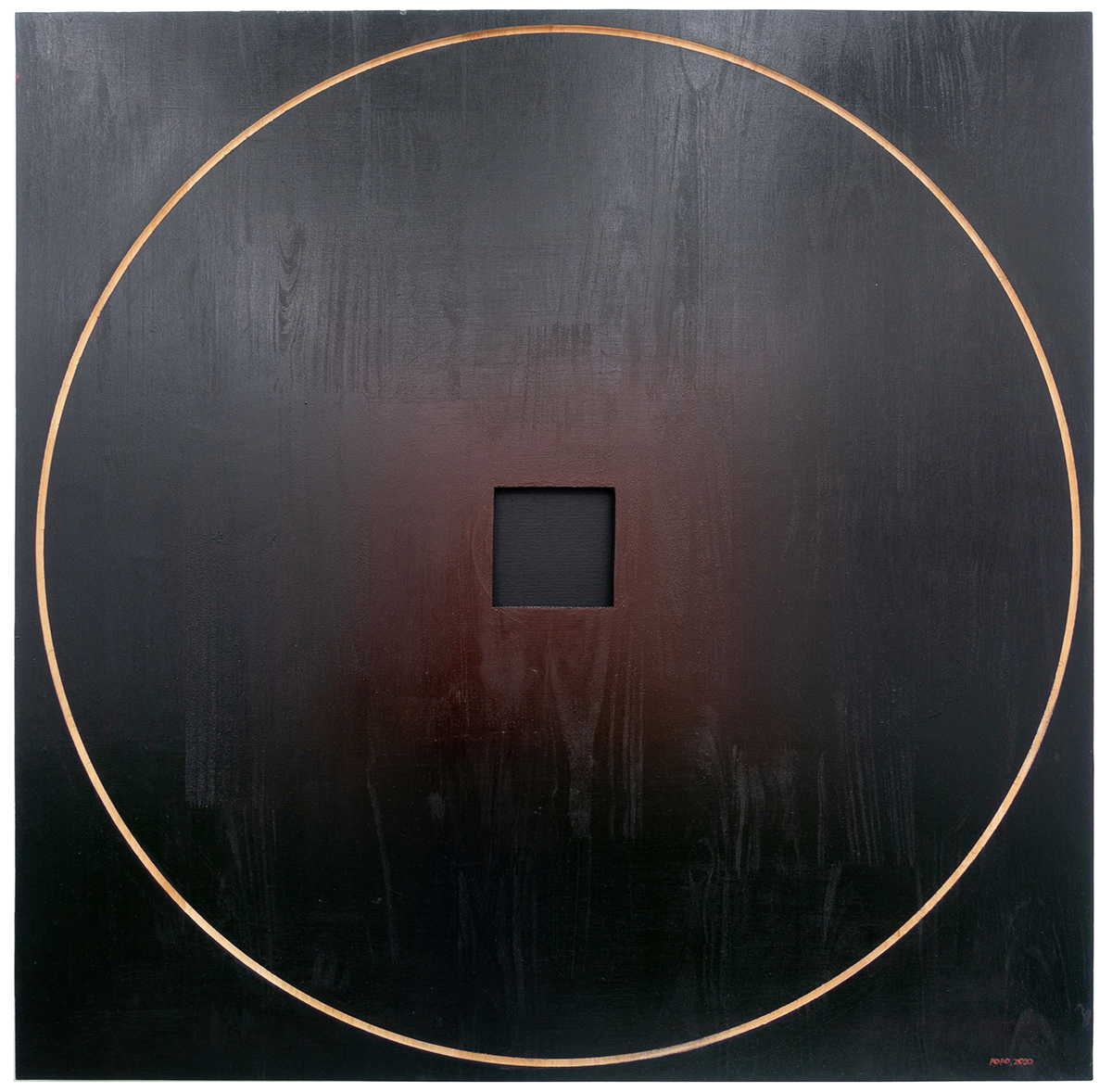

He speaks in codes that resist codification. But are there ways to get him? The exhibition title, Primeval Codes, suggests that he is trying to tap into something ancient and primitive about communication – a part that is more instinctive and unreasoning, perhaps even fundamental to life. Take the powerful, even talismanic image, Unknowable, which depicts the outline of a circle within the outline of a square, their sides touching. It is mathematical, almost fated: Leonardo Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man without the man. Against the solid black background, the circle glows thinly, the sun’s corona during a solar eclipse. Moon over Sun. Day, night, unknowable. Yes.

Po Po: Primeval Codes is on view at Yavuz Gallery, Singapore, through 9 September