A collaboration between Tino Seghal and footballer Juan Mata reflects the empathy of watching sports to find new affinities

When I started writing about football four years ago, I pinned a note to the cork board above my desk with a quote from Roland Barthes’s book What Is Sport? (1960) where he asks ‘Why? Why love sport?’ His answer is simple: ‘First, it must be remembered that everything happening to the player also happens to the spectator’. This meeting, this intense sense of relation, is always my first thought when people ask me, a football-obsessed art critic, about the connection I see between art and football.

Now there’s a new connection: a curated programme titled ‘The Trequartista: Art and Football United’ (a trequartista is an Italian term for a highly creative midfielder, the kind who can orchestrate a whole team’s actions) which will involve eleven professional footballers and eleven artists, co-curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist, curator and director of London’s Serpentine Galleries, and World Cup-winning footballer Juan Mata (the two met on Instagram, with Obrist slide-tackling into the footballer’s DMs). The first of these projects premiered as part of this year’s Manchester International Festival, a collaboration between performance artist Tino Sehgal and Mata called This entry. The other ten (artists and footballers as yet unnamed) will launch in the next edition of the festival in 2025.

Mata is interested in art and culture – he has described in interviews how much he loves the Whitworth Art Gallery, which he visited regularly in the nine years he spent playing for local giants Manchester United – whereas Sehgal is not a huge football fan. Yet Sehgal has always wanted to make a work about football. He compares the way footballers move to contemporary dance, saying that seeing footballers walking backwards on the pitch reminded him of experimental dancer Steve Paxton, a founding member of the influential Judson Dance Theater.

Trained in dance, Sehgal’s works combine storytelling (his large-scale commission for the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern in 2012, These associations, involved performers walking up to visitors and telling them personal stories) and choreography, like in This Variation, his work for Documenta 13 in 2013, in which performers invited visitors to dance with them in a dark room. With This entry Sehgal combines this interest in liveness with football’s specific relationship to time. A football match is an event completely dependent on the suspense of the present moment. The primal experience of football is this tension, the not-knowing what is going to happen next, the coming together: the jumping and hugging and shouting and booing and tears.

The footballer and the artist are not particularly forthright about the nature of their collaboration. Mata met with the performers in This entry, offering them intimate context on how an elite footballer moves and considers the space around them. Sehgal described how Mata gave the work context, his presence inspiring the performers to stretch their physical capabilities in order to create something new. The work brings together three artistic cyclists (a competitive sport also sometimes known as trick cycling), a pair of violinists, a pair of dancers (who also sing) and a trained footballer.

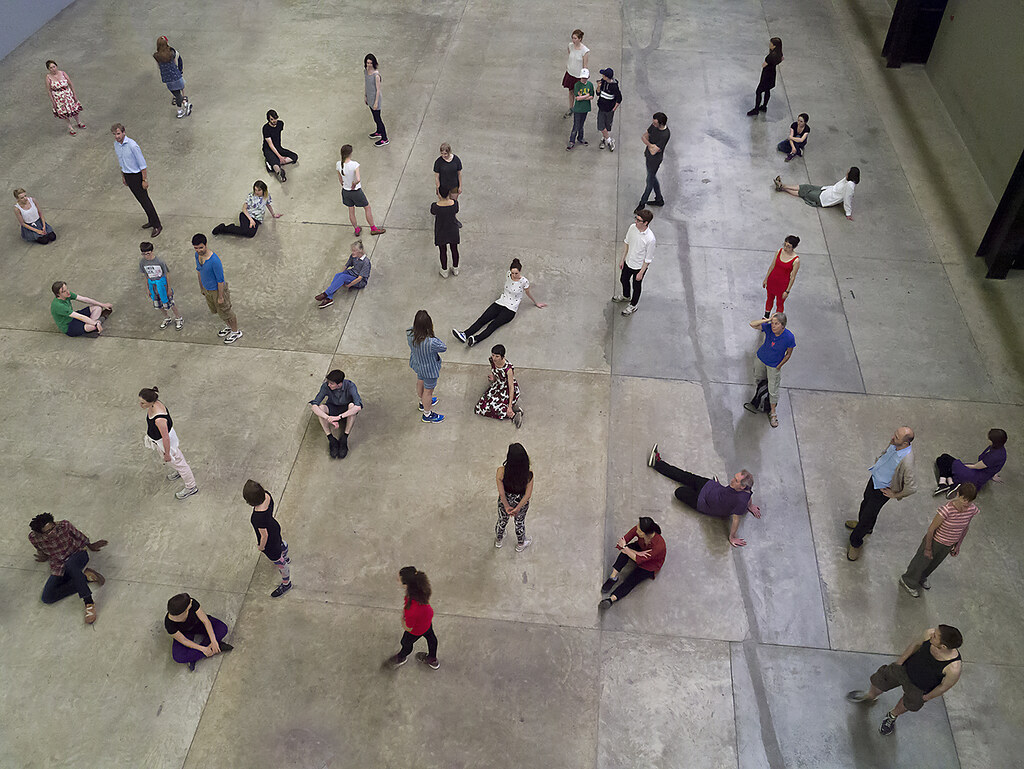

The participants in This entry play out a repertoire of movements and actions, with performers alone or together, improvising at times and embracing spontaneity. They move together, they break apart, they mirror each other. The cyclists perform tricks, riding while sitting on their handlebars, their legs stretched backward to reach the pedals. The violinist lies down on the ground while playing her instrument, or holds it upright just by her neck while singing a Dire Straits song. At times the violin feels mournful, at times the singing is funny (‘I want to ride my bicycle’). Next to her, someone is playing keepie-uppie with the football. One of the performers attempts to play football with one of the cyclists (she hits the ball back with her front wheel) and another dancer follows her, sitting next to the bike that the cyclist can keep motionless, as she balances a football on his head. There’s a levity in these physical exchanges that happens slowly and silently. Even though the performance doesn’t have a sense of linear progression, the performers come together in a way that reminds me of watching footballers: their seamless understanding of where each other is, their proximity, their connection.

This entry feels like true affinity: a dancer, an artistic cyclist, a footballer and a performer who all make meaning through their bodies, and stretch their physical capabilities in order to do something new in the world. Sehgal brings them together and their connection here feels earnest, each field an extension of the possibilities the other may present. Performed for a week at the atrium of the National Football Museum in Manchester, its floor demarcated with the lines of a football pitch for the performance, the work was then repeated at the Whitworth. The two very different institutions give two different contexts and potential audiences for the work. The Football Museum is dedicated to memorabilia and multimedia displays of the great moments in the history of English football; the Whitworth a university art gallery with a collection of artworks and changing contemporary art exhibitions. This entry creates a bond between these two worlds.

What is the connection between art and football? I usually think about experiencing football through media, how it’s a system of representation that artists are also interested in, the obvious example being Philippe Parreno and Douglas Gordon’s film Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait (2006), in which seventeen cameras followed the player in real-time for one game, exposing both the psychology and the beauty of the celebrated player on the pitch. This entry, unlike other art-and-football works, from Adel Abdessemed’s sculpture of Zidane from his last World Cup (Headbutt, 2012) to Kehinde Wiley’s 2010 portrait of Cameroonian player Samuel Eto’o, joins football in its liveness, in its exploration of this coming together.

This heightened awareness of the now as it unfolds is where Sehgal’s work feels new to me, even in comparison to other performance art pieces about football, like Eddie Peake’s Touch (2012), which involved a football match played inside London’s Royal Academy of Arts by all-naked players, in a work that explores masculinity and performance. It is the connection between the players, and between performers and spectators, that has always drawn me in. The humanity of it all. To watch sport, following Barthes, is a form of empathy, a connection in time through liveness and relation. Looking at This entry felt close to the intensity of watching football. Both involve paying close attention to another human being and feeling some sort of closeness, an affinity. It’s what I want from art, and from football too.

Orit Gat is a writer based in London, and a contributing editor at The White Review. She is writing a book about football titled If Anything Happens