How the intimate experience of mothering has been co-opted as a political tool for power

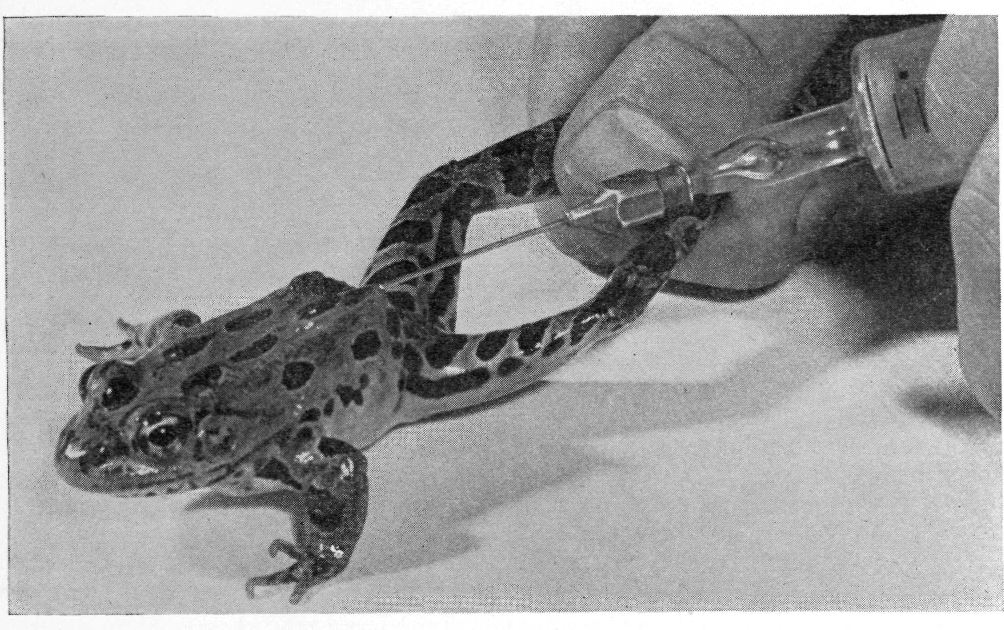

In 1927 two German scientists – Selmar Aschheim and Bernhard Zondek – invented the first lab-based pregnancy test. They would inject human urine into a female mouse or rat, before performing a dissection. If they discovered that the rodent’s ovaries were significantly enlarged then hCG (the hormone that is elevated in human pregnancy) was most likely present in the urine sample. In the 1940s rabbits replaced mice and rats; and ‘the rabbit died’ became a strange euphemism for pregnancy (strange not least for the fact that the rabbit died whether a pregnancy was detected or not). Later, frogs were also used, by which point hCG levels could be measured in the human-piss-filled animals without cutting them open. As Helen Chaman recounts in her book Mother State: A political history of motherhood, this form of pregnancy test was still common practice in the UK up until the mid-1960s. In an aside, Charman tells us that the international trade in African clawed frogs, which boomed to make these pregnancy tests possible, caused the spread of a lethal fungus that decimated frog populations worldwide; moreover, some of the frogs escaped and ‘colonised Wales’.

The asides, the human details in Charman’s otherwise fierce survey of the politics of motherhood in the UK, make for an exhilarating, if harrowing, read. No anecdote here is frivolous. Even the frog story serves to remind us that the project of making motherhood behave, of making it predictable, of making it make sense and not be unruly, has had frequently harmful consequences (and not just to rabbits or frogs or Wales). Charman charts a history of motherhood over the past 50-or-so years that focuses on how motherhood is ‘an entirely political state’ (relatively well-worn ground) but, uniquely, Charman also looks at how motherhood has been used as a political tool, how it serves power, how it has been weaponised to maintain the status quo, particularly by the governing bodies of Britain and Northern Ireland.

Charman’s starting point is really the moment the state began to lend a formal hand in the UK, with the postwar creation of the NHS and the introduction of more organised welfare; with the invention, in other words, not of a Mother State (for the system is never truly maternal, nor nurturing) but the ‘nanny state’ – which is a pejorative term used by those who find policies of social care and benefits too interventionist. But the term ‘nanny state’ closely describes the level of care actually available. After all, as Charman argues, the figure of the nanny in British society is ‘responsible for discipline’. The nanny is ‘untainted by the love we might assume to be the prerogative of a mother, [and she] wavers on the border of cruelty’. The British nanny state decides who is deserving of help, and who is not, and by using this rubric of ‘deserving mother’ rather than simply ‘mother’, the state lays out a blueprint for how a mother should be.

Margaret Thatcher’s decade as prime minister throughout the 1980s looms large in the book: her demure heartlessness. This is a history of how mothers have figured into states’ agendas even as they are fed the message that motherhood is private, domestic and intimate. Take, for example, the mothers of the miners’ strike of 1984, who rallied behind the picket. When the government withdrew benefits from those on strike it was assumed that these women would think of their hungry children and force their husbands back to work; that the women would bend and could be put to use. They resisted. The book covers this same pattern of bending, use and resistance, in ways sometimes subtle, sometimes vivid, through many examples from the decades-long eco-protests at the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp; to the invention of IVF; and the Depo-Provera scandal; there are chapters on abortion, contraception, single mothers, Cherie Blair (who gets a beating). But this is also a personal story: Charman occasionally weaves in snippets about her own single mother who worked for the NHS and was worn out by her employers. Charman, born in 1993, grew up ‘with a deeply held perception of myself as a New Labour baby’. She expresses her youthful confusion over what New Labour was (it was not, as she thought, socialism) and her bitter political disappointments at the reality the party brought.

Published in The Ohio Journal of Science, 1948

Charman’s cultural sourcing throughout is breathtaking, from Brecht to Ina May Gaskin. She hunts down Margaret Pine’s lost 1984 play, Not By Bread Alone; she draws our attention to the lesser-known work of Nell Dunn (not Talking to Women, 1965, but Living Like I Do, 1977) and calls on the work of British writer Joanna Biggs as well as EastEnders’ Kat Slater to bolster her points. There is a particularly haunting section on the uses motherhood was put to by both sides during The Troubles. The story, for instance (first reported in a book called Only the Rivers Run Free: Northern Ireland: The Women’s War, 1984) of Catherine in West Belfast, a mother of three, twenty-seven-years-old. Six years into her husband’s 12-year prison sentence for alleged membership to the IRA, Catherine had an affair and was pregnant. She went to Britain for an abortion and was detained on the way back. The guards threatened to tell her imprisoned husband of her pregnancy and termination, but wouldn’t if she agreed to became an informer. Catherine refused and so instead the guards taunted her husband with the story of her infidelity and abortion for the remainder of his sentence. ‘Women’s bodies were another territory upon which the lines of dispute were mapped,’ writes Charman. Mother State tells a story of ways in which motherhood has never been our own. ‘Not only is [the mother] responsible for keeping her own child safe, but the fate of the social fabric itself lies within her care.’

But the book also suggests ways in which motherhood shouldn’t be our own. In a section about communal living, Charman encourages us to really consider whether it’s acceptable to ‘own’ one’s own motherhood. Wouldn’t it be better to share the care and responsibility of children? Is this not the dream? Charman reports on communal living experiences, where people have tried (with various levels of success) to create an alternative to the nuclear family and share the parenting between many adults. But ‘even when the practical aspects of shared childcare worked, feelings of parental ownership were difficult to shake.’ Charman reports one woman’s frustration at mothers’ refusal to ‘give up a bit of their power’. This refusal, of the mothers to share their load with non-mothers, ‘speaks to a sublimated idea of an essential change that makes someone a mother, that equips them, somehow, for maternal work’, Charman writes. ‘Within this, perhaps, is fear: if you do let go of your power, how do you recalibrate your own relationship to your child? Acknowledging that care is work, and therefore can be learned, endangers the specialness of the category of mother.’

I’d argue there’s something potentially injurious, looming on the level of the psyche, to a child whose mother gives up her position without a fight. Doesn’t the child depend on that ‘specialness of the category’? Perhaps it should not be endangered, neither by state, nor by commune, nor by sharing. Charman, in a mosaic of stories, also provides us with the account of a mother who gave birth at a living community in Laurieston Hall, Dumfries, who describes the other adults around her thus: ‘They help without taking away my right to experience motherhood.’ A state organised around such a principle would be a true Mother State.

Roz Dineen is the author of Briefly Very Beautiful (2024)