Singapore’s anniversary provides an opportunity to reflect on the state of its art; or to discover what colour its art scene’s lenses are tinted

The early 1990s was an era of optimism in Singapore. The country was one of the high-growth economies dubbed the ‘Four Asian Tigers’ (alongside Hong Kong, South Korea and Taiwan), with average annual growth rates of seven percent; Goh Chok Tong took over from Lee Kuan Yew to become prime minister, promising a softer, more consultative form of politics; and the state got serious about nurturing an art scene, setting up the National Arts Council and Singapore Art Museum. While Singapore prospered from foreign investment, it was also a time of increasing anxiety regarding the pervasiveness of globalised, or more specifically ‘Western’, corruptive influences on a modern Asian city. Madonna, for example, was famously banned from performing in the city-state in 1993 due to the ‘obscene’ nature of her Girlie Show World Tour, which featured, among other theatrics, scenes of her dressed as a dominatrix surrounded by topless male dancers, and a simulated orgy.

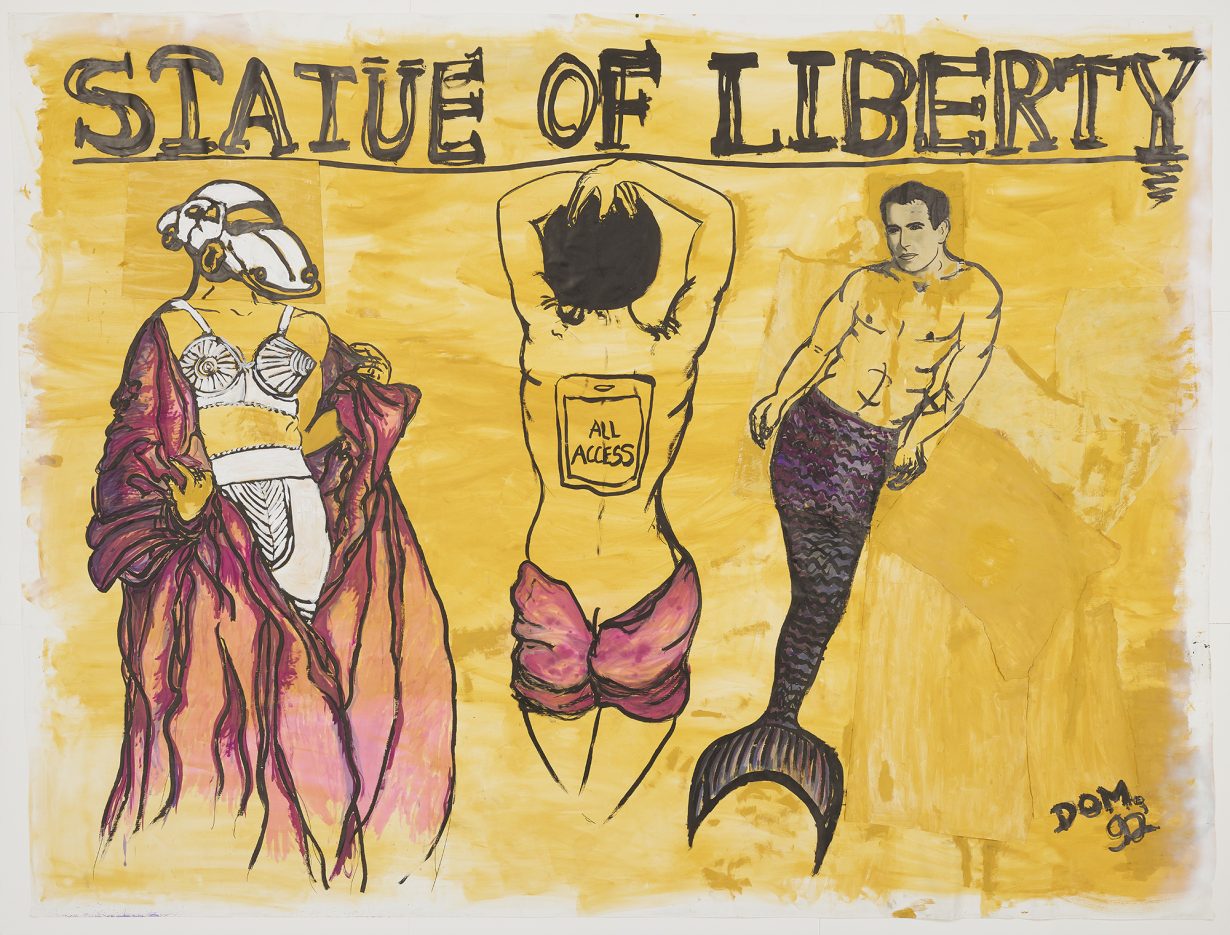

Singaporean artist Dominique Hui’s largescale mural Statue of Liberty (1992), featuring three figures of indeterminate gender, captures playful attitudes towards sex, materialism and American culture. The figure on the left is dressed in a Madonna-inspired conical bra and has a white car for a head; in the middle is a person, viewed from behind, shorts pulled halfway down their buttocks, bare back emblazoned with the words ‘ALL ACCESS’; on the right is a sinuously curved merman with the face of Jeff Koons, or more specifically, Koons’s self-depictions in his explicit Made in Heaven series from the 1980s and 90s, which comprised sculptures and paintings of him performing various sex acts with his partner, a Hungarian-Italian pornstar.

This mural, with its unabashed sexual openness and queering, is one of the prominent new inclusions in the National Gallery Singapore’s (NGS) first major rehang of its Singapore survey show since the institution’s opening in 2015. Titled Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art, the refreshed exhibition features some 350 artworks spanning the nineteenth century to the present. Together, they aim at telling a more inclusive and multifaceted narrative of Singaporean art. The revamp, which saw more than three-quarters of the permanent display rotated, was done to commemorate Singapore’s 60th year of independence (abbreviated SG60 in government publicity). As I write, SG60 events, which include a parade celebrating persons with disabilities, a religious and racial harmony month, and the National Day Parade, have unfolded across the island. Also jumping onto the SG60 train are businesses offering various deals and discounts.

The art scene is waving the Singapore flag with varying degrees of distance and self-reflectiveness. The state-funded not-for-profit Singapore Tyler Print Institute (STPI) is presenting Material Moves, which revisits the print and paper works of eminent local doyens such as Han Sai Por, Goh Beng Kwan, Ong Kim Seng and Chua Ek Kay. The commercial sector is taking advantage of the buzzy SG60 theme to present exhibitions that reflect critically on national identity. Fost Gallery’s The Lie of the Land: Sediments is a nuanced group show taking stock of Singapore’s history, with an emphasis on land, history and politics. At Loy Contemporary Art Gallery, artists Akai Chew, Joanna Maneckji and Wan Kyn Chan explore memory, identity and place in personal ways in SG60: To Build a Swing. Art Seasons presents David Chan’s solo National Identity 4.0, featuring paintings of local imagery like public housing, kampungs and nostalgic scenes of the past with irony and kitsch. Finally, there is Artist’s Proof: Singapore at 60, an ambitious account of Singapore’s art history as seen through the collection of former investment banker Chong Huai Seng – which can be seen as a foil to the NGS show. But more on that later.

As a flagship art institution, NGS leads the patriotic parade of shows in terms of scale, comprehensiveness and pro-establishment political correctness. It is an affirmative narrative about diverse artistic expressions unfolding alongside the evolution of a nation from postcolonial independence towards a flourishing, cosmopolitan city-state. Decades are, roughly, represented by thematic subheaders. The 1960s and 70s, for example, are sketched out in chapters such as ‘Expanding Horizons’ and ‘Vectors of the New’, where new forms of abstraction are linked to the soul-searching of a new republic, and exposure to international art-movements inspired local artists to find new idioms.

The ‘Imagining Nation’ section of the 1950s and 60s is particularly strong. Here history and art history interpenetrate climactically: anticolonial sentiment, nationalist aspirations and socialist concerns are matched by the creative grappling of artists trying to find a language authentic to their experiences and dreams. Significantly, the section reflects on class and class struggle – a divisive topic often elided in conversations about national identity and a significant challenge to Singapore’s sense of unity. In this section are representations of the workers who helped build modern Singapore. Among these are Lim Hak Tai’s Indian Workers Clearing the Jungle (1955), depicting sarong-clad, barebodied labourers hacking down palms painted in bold slashes of colour and Chua Mia Tee’s Workers in a Canteen (1974), a busy tableau of uniformed workers eating and chatting at the tuckshop at Jurong Shipyard. In Lim’s Riot (1955), he uses abstracted shapes and bold colours to depict a generalised scene of violent clashes between people, inspired partly by the Hock Lee Bus Riots (1955), a strike by unionised bus workers that turned into a riot that killed four people and injured 31.

In terms of diversity, the exhibition contains better representation of female and minority artists, at 23 percent and 24 percent respectively. (The gallery says this is an increase from the previous show but declined to say by how much.) New female artists presented a more rounded picture of creative production in Singapore, with the inclusion of fierce voices celebrating women in states of strength and vulnerability. Highlights include the works of Susie Wong, whose paintings of women, in spare compositions and flat planes of colour, meditate on mortality. The almost monochrome work Poh Poh (1992) depicts her grandmother with her hair pulled back into a bun, leaning her face onto her fist, looking at the viewer with a watchful, cautious expression. Womb Series #7 (1997) depicts a pale, female body curled up into a ball, with a huge expanse of thighs and haunches facing us, the face concealed but for a shock of white hair at the top.

As for LGBTQ+ representation, the inclusion of Hui’s mural could be seen as a sign of NGS’s greater openness to queer representation, which parallels government policy and Singapore’s increased social space. (Statue of Liberty’s gallery label reads: ‘In this work, gender is left intentionally open. Male, female and androgynous figures appear side by side, suggesting the fluid and contested views of gender during the 1990s.’ In the previous hang, there was no mention of queering in captions or section texts.) In 2022, Singapore repealed section 377A of the penal code, which criminalised male same-sex relations. This marked a significant first step towards expanding LGBTQ+ rights in Singapore, though representations of queer experiences in art and mass media are still often slapped with an advisory warning. NGS’s approach is cautious – a subtle nod as opposed to flying the rainbow flag – as can be seen in the lowkey placement of Hui’s poem, printed below eye level on an unobtrusive wall. It’s super-easy to miss. Published in The Substation’s catalogue to its The New Criteria exhibition in 1992, the text reads: ‘We are talking./ Talking to Singapore./ We believe in freedom./ We believe in revolutions…/ We believe in the arrival of Queer Nation/ Will inflate their plastic bananas./ We are prepared to be locked up/ Slowly, silently & brutally.’

To me, that ominous last line articulates what is left unsaid throughout this show – the looming threat of discipline from state apparatus – which goes towards explaining the limited inclusion within it of voices of resistance and dissent. This brings me to the main problem of Singapore Stories, which is not so much about the details of the art history it chronicles, but about the critical elements that are missing. There is a hesitation to portray artists who engaged in social critique or provided voices of resistance (not uncommon because of the government’s routine infringement on civic and human rights, and heavy-handed imposition of social controls), as well as alternative subjectivities and experiences that are messy, inconvenient and unphotogenic to the state-backed agenda of a flourishing ‘creative economy’.

One could argue that this pro-status-quo curating reflects social norms. Most Singaporeans are happy living under the rule of a paternalistic government that excels at what sociologist Chua Beng Huat calls ‘communitarian capitalism’, a unique model that blends elements of communitarianism and state capitalism, and with a good record of public housing, healthcare and economic development. If the cost of this is living in a more authoritarian than democratic polity, many find it an acceptable compromise. This year, the People’s Action Party (PAP) won 65.6 percent of the popular vote in the elections, marking an unbroken 60-year single-party rule since Singapore’s independence.

‘Singaporeans get the government they deserve,’ said Kenneth Jeyaretnam of the Reform Party, one of the opposition parties, in 2015 when the PAP won 70.1 percent of the popular vote. ‘I don’t want to hear anymore complaints.’ Similar feelings of defeat accompany my viewing of the show. Maybe NGS’s art history – safe, frictionless, neutered – is the art history that Singaporeans deserve.

That said, Jeyaretnam ran again in the next election. (And lost.) And for what it’s worth, I will not stop banging the drums for the emancipatory potential of art and how it can be an exceptional space in which we can escape all-pervasive control from hegemonic forces. Although it can be woefully commodified and instrumentalised by money and power, it is still one of the last crucial spaces of criticality and freedom, where preconceived ideological formulations can be destabilised and challenged.

So let’s talk about some of the gaps in NGS’s treatment of recent art history. Missing, for example, in both versions 1 and 2 of the Singapore survey, is Josef Ng’s seminal performance art piece Brother Cane (1994) – where homophobic laws and cultural censorship come together with lasting repercussions. Ng’s work protested a police sting operation that entrapped and jailed gay men. He whipped pieces of tofu with a cane and snipped his pubic hair, among other actions. Ng was arrested and fined, and the National Arts Council started an infamous ten-year funding ban of performance art.

To be fair, NGS is good at talking about and around Brother Cane without showing the actual work. The old display had a section text that devoted two paragraphs outlining the performance and its repercussions on the art scene. Brother Cane was mentioned in Singapore Sub Liminal (1994–2015) by Ray Langenbach, an experimental film recording the dreams of friends of Ng during his time of controversy, with artist Susie Lingham proclaiming that for the period of a year ‘we will renounce the use of our bodies’. If the old exhibition danced around Brother Cane, this current version buries it even further. The only Brother Cane reference is in a caption for Amanda Heng’s video Walking The Stool (1999), featuring the artist and her collaborators taking turns to drag a stool around the streets of Singapore, because performance art was banned in her government-leased studio. The caption states that Heng’s work was a ‘response to artistic restrictions in Singapore’ that were ‘part of a broader context in which the Singapore government had frozen funding for performance art for nearly a decade. This freeze followed Josef Ng’s controversial work Brother Cane in 1994.’ And that’s it.

Another omission happens in Gallery Three, which focuses on defunct alternative or artist-run art spaces, such as the chicken farm-turned-artist-commune in Ulu Sembawang run by The Artist Village and the gallery spaces operated by Plastique Kinetic Worms. They all get dedicated showcase sections. But not for 5th Passage, a pioneering artist-run art space at Parkway Parade, which happened to stage Brother Cane, or The Substation, Singapore’s longest-running independent art venue, which nurtured generations of local artists, indie musicians, theatremakers, filmmakers and writers, and is closely associated with civil society and activism.

Admittedly, 5th Passage and The Substation are art spaces and not art collectives, but their contributions to contemporary arts ecology in Singapore are historic and significant, especially in their expansion of civic, social and cultural space – which contribute to building national consciousness. NGS is happy to acknowledge the role that artist-run spaces played in nurturing experimentation and presenting a corrective to the commercialisation of art, but not so much when these spaces presented adversarial or radical perspectives that ran counter to the official nation-building enterprise, by carving out new understandings and practices of public and civic space in Singapore.

There is a more balanced and lively account of how local artists engage with sociopolitical issues at Artist’s Proof: Singapore at 60, which features over 90 artworks by 50 artists drawn from the private collection of former investment banker Chong Huai Seng. A strange, complex and personal show, it is as much a portrait of an individual collector, a depiction of the optimistic attitudes of an older, bougie, boomer generation of selfmade Singaporeans that benefitted from the country’s meritocratic system, as it is an eclectic and soul-searching journey through local art history.

Chong is part of what the government calls the ‘Merdeka Generation’, or Singaporeans born during the 1950s. A true-blue Singaporean success story, he was a scholarship kid who worked in the government’s Economic Development Board and later went into investment banking, among other ventures. He is a keen admirer of the pioneering generation of Singapore politicians. A bronze bust of Singapore’s first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, by British sculptor Sydney Harpley, which was made in 1982, is the centrepiece of the show. Around it are displayed portraits of key figures in Singapore’s first cabinet and founding members of the PAP, Goh Keng Swee and S. Rajaratnam. So we know that Chong is an establishment man.

Yet the exhibition, which is again organised in thematic clusters, still provides pockets of freedom to explore alternative positions, such as a more defiant tradition in the face of the punitive aspects of the PAP’s authoritarian rule. In LKY’s Office and CTP’s Room (both 2016), two paintings by Jon Chan, the austere working spaces of two very different politicians with huge power differentials, are captured side by side. One work depicts Lee Kuan Yew’s minimal, book-lined office; the other shows the single-room guardhouse abode on Sentosa where Singapore’s longest-held political prisoner, Chia Thye Poh, was confined, after already being imprisoned for 23 years without trial.

While Josef Ng was missing from NGS, he is prominently featured in Sonny Liew’s reference-packed P.A.P. x P.A. (2025), which comprises specially made action figures of Lee Kuan Yew, Goh Keng Swee and S. Rajaratnam, as well as numerous references to key performance-art events. Each doll is packed with different accessories, such as a pair of scissors, a cigarette, a cane, tofu and red dye, all of which are props from Ng’s performance. There are other in-jokes for viewers privy to Singapore history, such as the words printed on the jacket of the Lee Kuan Yew doll, ‘a luxury we can now afford’, a reference to his infamous but unverified quote ‘poetry is a luxury we can’t afford’ – illustrating how pragmatic and censorious the pap old guard was with regard to culture.

Finally and more importantly, Artist’s Proof also takes on the exclusions, marginalisations and otherings of Singaporean identity. Represented, for example, are migrant labourers, who have an ambiguous status as vital residents but not quite citizens – who live in dormitories at the edges of the city, contributing to nation-building and yet considered foreign, transient and dispensable. An example is David Chan’s diptych painting #firefire (2017), which references the 2013 Little India bus riot, the first riot in Singapore in over 40 years. Some 300 migrant labourers attacked emergency vehicles after a Bangladeshi worker was hit and killed by a bus. One panel depicts an ambulance tipped over on its side and up in flames – a scene from the riot. The other panel shows a mysterious scene of people cheering in front of a fire. The artist says the latter tableau is inspired by campfires in secondary schools, but the blurry image is ambiguous: this could be a celebration, ritual or protest. It’s an enigmatic work that juxtaposes two incendiary scenes hinting at the potential for destruction and the fear of loss of control.

Discomfort is key in any national survey worth its salt. Nationhood is a construct, but it is also a contested territory. By highlighting artists who unsettle the idea of a fixed national identity and drawing attention to its divisions, exclusions and entrenched asymmetries of power, this show presents a more authentic picture of lived experiences in this flawed, infuriating and paradoxical work-in-progress of a country. Singaporean poet and playwright Alfian Sa’at once said, ‘If you care too much about Singapore, first it’ll break your spirit, and finally it will break your heart.’ There’s disappointment here, but also love. Any story about Singapore art, or Singapore for that matter, that doesn’t acknowledge the heartbreak is not a true or loving one, and one that cannot allow the movement towards repair.

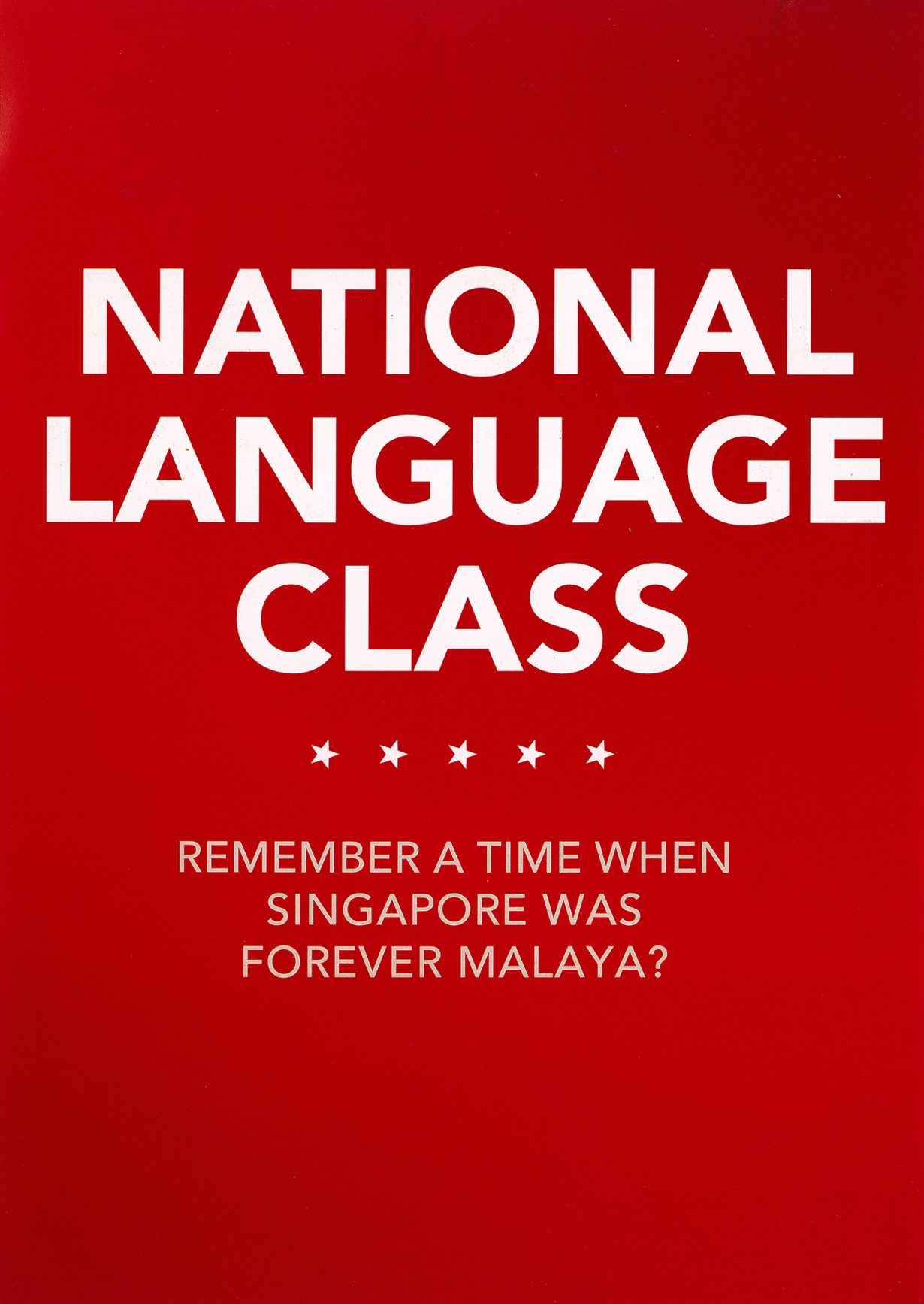

In this regard, a work in the NGS show, Chua Mia Tee’s iconic painting National Language Class (1959), provides a fruitful way to think about national identity. The work is as slippery, fresh and relevant today as during the tumultuous time of its creation, when Singapore was granted full self-government from the British. National Language Class is set in a classroom, where a group of Chinese students are gathered to learn Malay, the newly designated national language for a multiracial country. The reception is mixed. Amid eager faces is a man staring straight at the audience (often identified as the artist) with a fierce, wary gaze. On the blackboard are questions in Malay: ‘Siapa nama kamu?’ (what is your name?) and ‘Di mana awak tinggal?’ (where do you live?). The painting suggests that forging a national identity is by no means ‘natural’, but is instead instructed and constructed; it involves effort and discomfort, akin to the process of learning a different tongue. And in creating narratives about nation-building, perhaps we can all take a leaf from that young man holding our gaze, which is to engage with such projects with a healthy dose of scepticism. The fundamental lesson from National Language Class, at least to me, is to view national consciousness as a participatory and pragmatic process of consensus-building, with a dynamic, animating layer of contention and difference – the concept implies unity and disunity.

Singapore Stories: Pathways and Detours in Art, a rehanging of the permanent collection, is ongoing at National Gallery Singapore

From the Autumn 2025 issue of ArtReview Asia – get your copy.

Read next On a tour of Singapore’s seasonal gallery offerings, Adeline Chia recounts the dreamscapes and hollow-eyed monkeys she spotted along the way