‘You have to fight for every inch. Decentralisation vs hierarchy, trust vs control… Documenta should really think how it operates and try to find a different economic model, in order not to become centred, extractive and exploitative because of its scale’

Directed by the Indonesia-based collective ruangrupa, documenta fifteen, which opened in Kassel in June, confounded many assumptions about how this major survey exhibition should be organised, and who and what it should be for. Under their model of ‘lumbung’, the Indonesian term for a communal rice-barn, ruangrupa have attempted a radically different way of organising and sharing Documenta’s financial and institutional resources among a huge number of artists and associates.

Add to this the controversy that has dogged the exhibition over allegations of anti-Semitism in some of the works presented, and documenta fifteen will go down as one of the more provocative and polarising editions of the German mega-exhibition to date. As the show came to the end of its 100-day run, ArtReview’s Mark Rappolt and J.J. Charlesworth spoke to ruangrupa’s farid rakun and Ade Darmawan about their hopes for and the results of ruangrupa’s artistic direction of documenta fifteen, and what happens next.

Mark Rappolt How did you react initially when the invitation to curate Documenta came about? Was it something you were already interested in, or did you have to think about it?

farid rakun We were not even aware of our candidacy. One of the finding-committee members had put our name in the hat for them to discuss further. We were surprised when they told us, because we never thought that something like Documenta would work with something like us. They run on two different ‘operating systems’.

MR Can you say a bit more about that – what were the differences?

FR We knew about Documenta, of course. But from secondary sources like the media. That type of object-based art, one curatorial voice, genius in art and so on – we haven’t worked liked that much before. So we knew it was going to be tough to act as a curator, or a classic, centred artistic-director.

But we were transparent from the beginning that what we were going to do is what we are already doing anyway. People might argue whether what we do is curating, but for us, this is what we do. That’s the work that we agreed with the institution as well.

Ade Darmawan I remember one of the finding committee, when he was coming to us, asked us if we would be interested in sending them a sort of plan; he was giving us this news as if it were bad news rather than good news, because it’s still a long process of selection. So we discussed it as a group. I think our hesitation at that time was because we had just moved into a new space further to the south of Jakarta, where we were setting up a ‘collective of collectives’, with a few others with whom we had worked already for many years: Serrum and Grafis Huru Hara. That started in 2017 and 2018 with two big warehouses.

We were still quite wobbly with many things – things that we thought we should work on in our premises, in our system artistically – and then we were setting up [the educational platform] Gudskul, and so on. The answer for us was that it would only make sense if Documenta should be a part of our journey as well. Rather than we go and be exploited by it… Which is what’s happening now, I think. [laughs]

It’s more like how we envision our journey, and then how actually to do this Documenta as being part of this journey. The big question is, ‘What is it for us?’ ‘What does it mean for us doing things and working in different contexts?’, which is the question, in our mind, every time we do projects outside our locality: not only what it means for ‘us’, but also what it means for ‘them’ – for people, or for places that we’re involved with. We did it as well, not as a curator but as artists.

So finally, we wrote those texts that they had asked for based on this way of thinking, and then we extended it to many practices or models that we might want to learn from. It’s not really thinking about making an exhibition, that’s not in our mindset. It’s really about who we should like to work with, be inspired by, learn from and so on in the longer term, rather than thinking about what to show, what to exhibit. That wasn’t in our minds.

We were pretty surprised that it actually got to the next phase. So we wrote a longer plan. But we were thinking that with or without Documenta, we’re going to do this anyway.

MR I guess I want to follow up on what farid was hinting at before, in terms of this not being a Documenta about individual artworks and individual geniuses. Did you set out, when you were planning it, to introduce a different model? To what extent is that model an attack on the prevalent model in, let’s say, Western museums or even places outside the West that adopt Western models?

FR I think, if we reflect on what we are doing already anyway, that is the thread. We want to learn about models and we know about the extractive thing, we know that exploitative thing [of the Western exhibition model]. But there are some individual artists in the roster. What’s important is that they work not solely as one person, that it has function or impact, that it also works in the ‘ekosistem’, as we call it [the idea of collaborative network structures].

We are not against objects, of course. We like beautiful objects, beautiful videos, beautiful sculptures, all that kind of stuff, paintings… The question is just how do they function in real life as well, or in other people’s lives? I think that’s in the thread. Being ‘anti-something’ is a way of thinking that got imported into Indonesia; in our language there’s no word for ‘anti’.

MR You’re talking about ways of working that are integrated into context and the reality of specific situations (Indonesia in this case). How do you import that to somewhere like Kassel?

AD That’s actually a challenge that we find in many projects. We are already several generations in ruangrupa; many of us are also artists or studied art. I studied art. This thing has colonised our minds as well, even when we work as individual artists. It’s actually never really gone away. Also, as a language, it’s there. We use the artistic or poetic language, and we still believe in it in many ways, of course. But this translation, this bringing one practice to another place, it’s always a challenge when we are being curators, either individually or collectively, or being artists, individually or collectively.

In this Documenta, I don’t know if it works – maybe it needs some really deep analysing – but at least we tried to see it from the perspective of how resources work. We always see it as a movement from one place to the other place, and then the work is either recontextualised or it’s a challenge. But this distance also makes the work representational.

So, what we are trying to do – at least during our research conversation with a lot of artists and also between us – is think about how to make that movement into a cycle. That’s why there’s always this question: what does that mean? If we invite Jatiwangi Art Factory from Jatiwangi village in West Java, Indonesia, to Kassel, then it shouldn’t stop there; it should also be cycled back. That cycle only makes sense if we think about the logic of resources.

I don’t know if it works or not, but at least we tried to tackle that question about this different context. We are thinking not only about Documenta as an exhibition that ends or stops, but also thinking about this as a ‘lumbung journey’ that goes beyond Documenta; can exhibition-thinking go beyond itself? I think that’s the only way, at least for us, now to tackle that idea of distance and time. We are stretching it.

MR But I guess when you’re saying that, it’s also that a number of the collectives and participants (thinking of things like the Off-Biennale from Budapest, yourself and Taring Padi, to some degree) are constructed because of the denial of resources, the denial of facilities and the denial of – or nonexistence of – infrastructure. That seems to me to be a bit of a challenge when you suddenly arrive at an organisation that has resources and an infrastructure, that is the very opposite from the situation in which these collectives were born.

FR Yes. That’s also another understanding of different ‘software’, a different ‘operating system’. At least for now, we learned that having more resources – in the sense of financial resources, spotlight or attention resources – doesn’t mean that it’s actually better. It’s not necessarily the thing that maintains or sustains certain things.

What we learn is that while it is a privileged position to have something like Documenta as part of our journey, it’s also sometimes like smoke and mirrors. From the surface it’s as if it’s big and all that kind of stuff. But it’s not ‘the sky’s the limit’ – we know it’s not – especially when we want to make decisions together and be transparent towards each other.

Compared to other big contemporary art events, the rhythm of Documenta is considerably longer – every five years. We worked on it for three years, but then – and COVID made it worse – it’s still not enough time, always not enough time. The calculation, or the tradition of making an exhibition of a certain scale, hits you with certain things that you cannot rush. That becomes kind of a battleground, let’s say.

MR Do you think after this, you would do another largescale exhibition as artistic director? [farid and Ade laugh]

J.J. Charlesworth I’m interested in the experience of the exhibition from the perspective of the visitor, which has something to do with what you mentioned early on about ‘operating systems’, and what the priorities are to make an exhibition. Even though I was running around like a crazy person, trying see everything and failing to spend time with works during the press preview, many of the works and events were being presented for very different reasons than to exhibit visual art to a public – to create spaces for different groups of participants, to stage meetings, provide documentation and information, and so on. This is something of a paradox. What I enjoyed in documenta fifteen was that there are lots of works that are ‘turning their backs’ to you.

It caused quite a few problems, but it was worth doing, because it highlighted what you expect from a big show, who you expect it to be for. It’s interesting to come across some of the presentations like [Marrakech cultural space] LE18, which had a long text by the group explaining why they had to resist the kind of ‘siren call’ to ‘make a show’.

It poses the question of whether you wanted it to be an exhibition at all, and not a meeting or a conference, because there is no sense in which this is a beautifully curated, presented experience where nobody’s going to feel uncomfortable.

AD I can elaborate on that from a different angle maybe. There is the development, over 22 years now, of ruangrupa; we started as artists and an artist group, and then slowly became more collaborative, more collective and so on. (Although we never really used that word ‘collaborative’ actually.) But that collaboration with different people from different disciplines comes from necessity as well: we like many things, we don’t only like one thing.

We like music, we play music, we make festivals, we like to host, so there are so many things – we never really believe in just doing one thing. We’re always trying to put other sensible or sensorial elements into what we do. We never really make a ‘singular’ exhibition, maybe because we never really believe in it. Or maybe we think that it’s not enough, or we think maybe it should also be experienced in a different and diverse way.

We never really see space as a white cube that only functions for exhibiting work. For example, we use the space for gigs, for meetings, for gatherings, living, sleeping and so on. Which is also resonant with practices from different parts of the world. We can go from that to how we struggle with the space, which has a special practice and special contexts politically, in one locale. With opening up space – a contested entity in relation to many things surrounding it. So, when we involve other friends, partners, collaborators, who don’t have the same but similar ways of thinking of approaching the space, arts and audience in that way, it just becomes natural that this mixture of different languages and strategies towards space, towards the exhibition, towards the audience, will emerge.

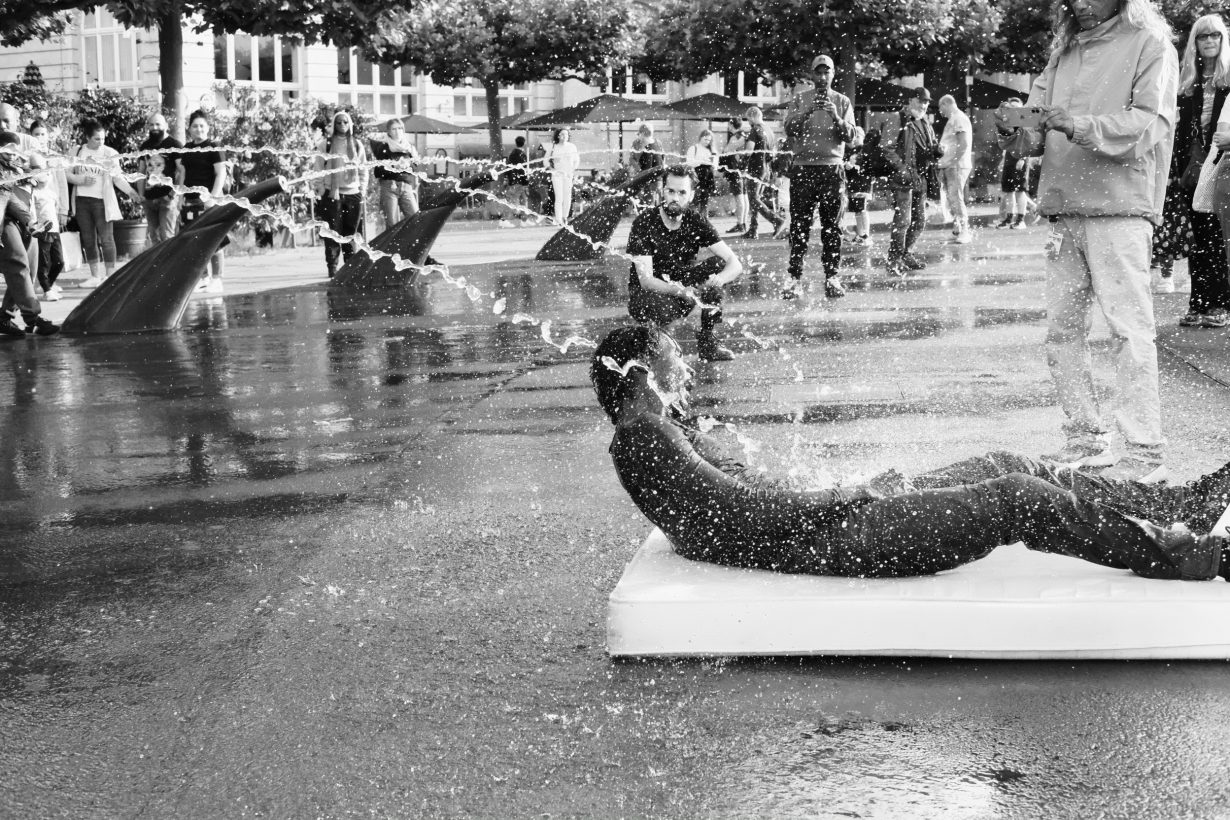

For example, we never really decided that venues should become living spaces; it just came naturally. It’s coming from the needs of many practices that we invite, that they want to do that. Some part of [Documenta headquarters] the Fridericianum has actually become a dormitory, some part of WH22 becomes living space, the Hübner space as well. It’s actually a natural approach somehow. Maybe that’s why also it’s become strong, in a way, because it’s become a living form of action.

JJC I remember saying in the office, slightly flippantly, that I had a feeling that ruangrupa were going to ‘crash Documenta’. But seriously, it is evident in a lot of the tensions that seem to have emerged that actually the Documenta structure, however willing it was to entertain alternatives, is still a very hierarchical or very centralising structure, with quite a few unscrutinised assumptions about what the exhibition should be.

I wonder, were you anticipating that the different ‘operating systems’ would cause such friction, whether the Documenta team anticipated it? More generally, what did you think of or work through ahead of the situation?

AD Well, it started not from day one but from before! When, finally, they appointed us, we had to deal with the contract. They sent us a contract and it’s actually for an individual artistic director while we are a collective. We hadn’t started yet but this is a sort of crash already. We know that maybe we underestimated that this was not going to be a big crash!

It was tough, very tough, because this is not a show with a ‘theme’ in the middle, and then the works will react to it. And it’s not only based on the production mode, in the Documenta tradition, but also how the exhibition is perceived structurally. Lumbung is a practice, it’s a way of working based on certain principles and values. So we have to apply lumbung values in our modes and approaches: from how we do our artistic research, how we see audiences, the exhibition, the Documenta economy, time, space, resources, etc. I think it has also something to do with how Documenta, after Documenta 14 [in 2017] also changed their structure, which has become more controlled. Obviously, they had to restructure after…

JJC … the deficit crisis of Documenta 14?

AD Yes. It used to be that the artistic director and managing director were on an equal level. They used to be able to do whatever they wanted. But now they put in a ‘CEO’, they changed it. It has this element to it that is more controlled. So, I think when we started with all these changes within the organisation of resources – how we work with the management, and so on and so forth – it’s not easy. You have to fight for every inch. Decentralisation vs hierarchy, trust vs control…

FR I think we knew it was going to be a negotiation from the get-go. This result, what you experienced, although it’s only for 48 hours as you say, is a result of that. We cannot say otherwise, we should not pretend that it’s the other way around.

What we realised, after all these things, not only in ruangrupa, but also with the artistic team, with some of the artists and collaborators, is that we should not have started this with Documenta; we should have started working like this even before, so that the network would have been built before, basically.

We also call it ‘Lumbung: Documenta version’, with COVID included; COVID makes everything different. But then it is a Documenta. Luckily, at least up until now, we’re still thinking together about what the next version could be. It becomes like a journey in itself or a type of music that can be revisited, revisited, revisited again. Technically, and also, of course, talking about resources, we put the economy in front. It happened. Yes, it’s still happening, of course, but then it’s the media furore about it. Partially, a German media furore about it. It becomes politicised. It came as a surprise for us.

MR I guess to some degree that had already started before the show even opened.

FR Yes. It was surprising for us. That’s why we needed time. We are also slow – meaning collective. We needed five months since January before we reacted as ruangrupa and the artistic team. Before we just listened to other voices, because this is like a fight or a struggle that we came in the middle of. It didn’t start with us. It’s not going to end with us. Where should we position ourselves in all this? We know our voice, or we know our collaborators’ voices, but it’s much more like, ‘OK, how should we put ourselves into it?’

MR In hindsight, given the controversy of Taring Padi, would you have policed the exhibition more? Could you even do that?

FR The way we do documenta fifteen, participants are maybe staging ten different exhibitions during the hundred days, and we trust them. Also, with COVID, we were never able to meet everyone in person before maybe two months, a month before an exhibition opens. So even if we wanted to, we wouldn’t be able to control everything.

MR That’s in the nature of how a lot of the work is made as well.

FR The way we understand it at least is two sides of the same coin. The way documenta fifteen would be achieved, let’s say, means this is not a bulletproof thing. This is, like you said, maybe a new way to do a Documenta. A lot of people, including ourselves, don’t know how to foresee things before they happen. We knew that there were going to be a lot of surprises. Some will be good, or most will be good, but also there is a big risk in some of the surprises. We see it as a challenge. The way we see it right now, at least, it’s part of that steep learning curve. Learning about institutions like Documenta in Germany, or even in the Netherlands, or maybe in the UK, there’s nothing like it. The closeness of politicians to an art show, and that it can be considered as a state project, and all that kind of stuff.

MR Also the sheer hysteria of the German press. There was one really crazy article in Die Welt that said something along the lines of ‘if you thought Documenta was riddled with anti-Semitism, you should go check out HKW, because that’s a viper’s nest of anti-Semites’.

JJC I have many misgivings about the controversy. First of all, at a trivial level, it was actually hard to see the works in question…

FR Taring Padi, you mean?

JJC Yes. You had to know what you were looking for and go and find it. I am careful how to frame this because I’m not a particular fan of, say, BDS, politically, or rather the European artworld’s obsessive attention to Israel and Palestine. But nor am I a fan of censorship, whether it’s by the German state or by social media, or by people who want to exclude, for example, artists who are from Israel. There’s a lot of censorship flying around in the culture. So I think that the works in question should be seen, so that people can judge for themselves.

I think there’s also a level of absurdity and hysteria when you actually see some of the things which are being singled out. In particular, the most recent story was about material that was ‘discovered’ in the Archives des luttes des femmes en Algérie [Archives of Women’s Struggles in Algeria]. If you’re telling me that Palestinian liberation movements are never going to caricature Israeli military or security forces, and also that we can never see this material, I think you must be out of your mind, because this is a historical document, it’s a political document, an archive. You may not agree with it, but the idea that one can never look at this material as a historical document seems very regressive.

But I think there’s a lot of unacknowledged resentment and frustration in a lot of these controversies, and this one I think is also one of them, whereby the people are wondering why art has become so full of politics. Obviously, there is a partisan issue: there’s an issue about why a big official institutional or semi-official institution like Documenta should appear to be presenting one side of what are bigger political controversies. I don’t particularly want to take sides, so for me it’s more important to try and work out how the presentation of political art is in tension with the institutions that present it. It goes back to what you were saying about how these two different structures may be incompatible. The context for this is a bigger discussion about how artists work with politics, and work politically, how they engage that kind of practice with institutions which may actually be quite conservative institutions. And yet, these institutions want to let you in. That’s the interesting thing. You were not excluded. You were invited in.

AD I would like to go back a little, because we have a way of working, and then when we expand our conversation, and we’re really interested in the models of struggles, speculation about models of education, economy, activism and so on, we’re interested in a certain model or approach, so we extend that similar approach in different places to connect and to enter a conversation. That’s actually how all the struggles are actually connected in many ways.

They are marginalised, they’re really struggles within our contemporary world, in many ways. That’s actually the connection. There is no ‘theme’. Because many times, this is why maybe the sloganistic or rhetorical approach of a lot of political artists, or of political art, is not working, not cracking the system, or not trying to make a space, or a different system, or different models. For example, many of the practices in this Documenta are really onto that, with a different language. Hopefully, people will see that it’s more inherently political, rather than being a representation of politics.

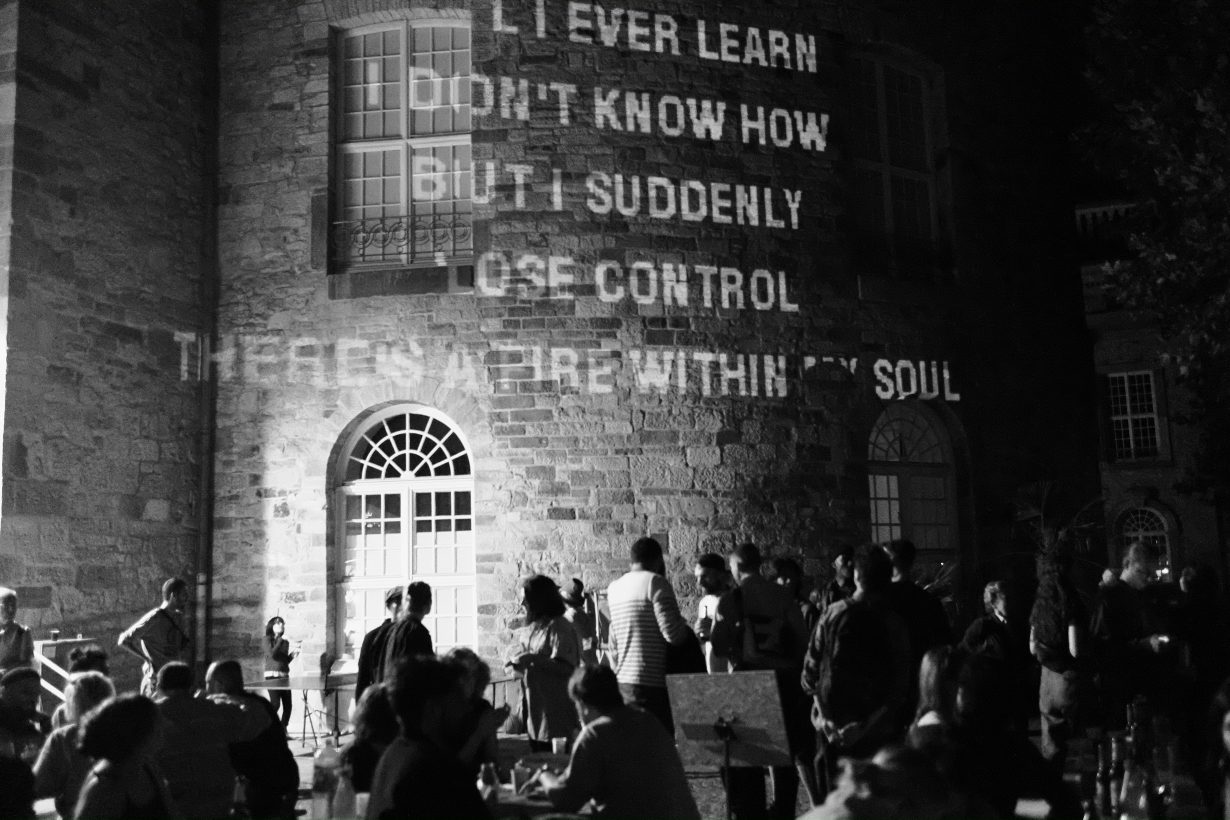

Rather, it’s an action. You’re setting up a school with a different model. It is political in many ways and in many places. It’s not that we’re talking about how this world should be this way or that, this kind of shit, but really doing it. That’s why it’s actually also a different energy. I like when you mentioned the word ‘conference’, because I see it that way as well. It’s become a big conference, when actually the participants, the artists, the collectives, collaborators, just gather and meet each other.

That’s why I’m really interested how it actually works after Documenta. I think for now the points are taken. That’s it. I don’t mind if it stopped tomorrow. I don’t need a hundred days. But if a hundred days can really facilitate people to meet, to conference, basically with all the struggles, models, I think this, the hybrid, the ripples it causes, that should be really exciting to see, because again, talking about resources, we now meet – and before, all these struggles never met, never.

Unless you were in the artworld elitist circle, with the stamp of political artists; then you can go around international biennials, which basically can be only afforded by countries that have infrastructure and resources to do that. Like, for example, how an Indonesian will meet other artists from the Southeast Asian region, but in Singapore. It would be great if these connections could be made directly, straightforwardly between and among them. We’ll see after this. I think that will be actually the work of documenta fifteen that I will be happy with.

MR I guess we should briefly discuss some of the other bits of the controversy. I think, for instance, there were writers talking about how you had no Jewish Israeli artists in the show, and what your standpoint is on anti-Semitism – maybe you can talk a bit about that?

AD We never see this [Documenta] in terms of representing nation-states. That’s one thing. I think many of the practices presented here are actually against state structures, ideas and so on. So we don’t see that way. It’s like that approach or statement is somehow for me irrelevant…

MR Yes, but it’s a particularly Western institutional context – that need for everything to be represented…

AD There have been no Indonesian artists in the history of Documenta…

JJC I would come back to the idea that artistic directors get to choose who they want in their show, and that you have the authority to include or exclude. In the end, it’s up to you, surely. I think that Mark’s point about representation is an interesting one because it goes back again to the idea that Documenta must have this kind of global authority. I’m not sure about that…

FR J.J.’s reading is quite a generous one and useful as well for us to hear that from you, because up until now, a lot of times the questions become repetitive and it’s not challenging. On the matter of representation, as Ade said, we didn’t want to answer that particular accusation, because we never thought about Documenta as being representational. A lot of people, artists, don’t want to be identified as being from a certain country. We don’t want to say that we represent Indonesia, for example, nor Taring Padi either, I would say.

Second, there are Israeli and Jewish participants, but we never ask people about their race or ethnic group, or whatever. For a long time, we didn’t know whether it’s true or not, whether there are Israeli or Jewish artists in these 1,500 artists that we are working with. Then we found out after that there are. Thirdly, although we didn’t ask, some later let us know that they were actually Israeli Jewish, for example, or Jewish, and some of them asked us not to disclose that, so we respect that.

MR It’s noticeable that much of the criticism comes from a German perspective and from a German history – and a German psychology to some degree – without any acknowledgments of who you are, where you’re from, where the other people are from, who they are.

AD It’s always self-centric, European-centric thinking, all the time in many ways, and in art as well. It’s really become a hurtful conversation. We can say that it’s a double standard, that it’s self-centred. I think the controversy really shows that it is like that. I don’t know how hopeful I am that people will learn and analyse this, but it is hurtful. In this tornado, a few times we were saying to ourselves, ‘Why are we doing this? Are we obliged to teach Europe? Are we obliged to fix Europe? What about our struggle? What about other struggles?’ and so on…

It’s maybe like we have to choose. It’s really relevant also for us because we have a lot of people back home here in Indonesia, wondering what this lumbung will mean for us after Documenta and so on. Then at the same time we are being sucked into this discussion. It’s really about that as well, about which direction we should take this.

MR Will there be a positive impact from Documenta within Indonesia and the art scene at home? I guess tourists will know one new word: lumbung.

AD We are developing, together with many other collectives in different islands as well, Lumbung Indonesia. It has a different context and challenges but it’s also a model that they are developing so everyone can learn from each other. A few of them are collectives or initiatives that have already been existing for many years, but most of them are from younger generation. We’re going to get busy with that and see. It is important to see that it will be more towards the direction of educational and economic models. Of course, many places like Indonesia have been modernised, Westernised, yet in some strange ways that aren’t quite there. Especially because Indonesia is vast and very diverse. It’s awkward. It’s not fully colonised as such…

MR But it’s like when Indonesia had the revolution, you couldn’t decide what language it was to be in…

AD Exactly, too many languages. I think that’s actually the homework that we have to do. Of course, we deal with art institutions here, and also educational institutions. We just have to go for it more and really envision that [lumbung] as a practice that can be adapted and can learn from many different localities. Because for example the economic model that we are proposing, it’s not there yet, but we have to experiment more, it needs time. There’s a lot of homework. I think people will also more and more be part of it.

I have a suspicion that Europe will adapt this model in their own way faster because they have resources. We could see also from the last two years, during the preparation for Documenta, there were many people writing, and institutions, art schools, museums, really looking at what we were doing. But in Asia-Pacific, museums, big institutions, biennials, really still would like to be Western institutions. We’ll see how these two opposite streams will meet in the middle and overlap.

MR At first all exhibitions I saw were in shopping malls in Singapore and Malaysia – because there weren’t really other spaces. It seemed normal after a while.

AD` Yes, in Bangkok also.

JJC That is a function of what we assume an art exhibition to be. I think that many of the things that you have had to suffer in this situation in Kassel are coming from a crisis of the public institution in the European and North American models. Yet those models have been exported, or have been often assimilated by other cultures, particularly in Asia, where those societies are becoming much more wealthy and much more leisured, and much more middle-class, it’s clear that you’ve walked into problems that are internal to the institutional culture of contemporary art in Europe.

My question to Ade is: ruangrupa has always been based on dealing with the lack of resources and dealing with the lack of infrastructure. But what happens when Indonesia has an exhibition institution as big as a Documenta? Will you still get into so much trouble?

AD It’s a good question. I think Indonesia had that infrastructure actually pretty early in the region. Jakarta Arts Centre – Taman Ismail Marzuki (TIM) was built in 1968, and Jakarta Biennale started back in 1974. That’s how in the 1960s the government played a role in the development and the planning of arts infrastructure in the context of the institutions and fields of modern art. During the Suharto regime (the New Order Era) cultural centres were built in each province as part of the cultural politics of national identity. When we started in 2000, we were writing a text about more or less why and how it was necessary that we start ruangrupa. One of the things that we pointed out back then is the lack of infrastructure, but to think back again that is actually not completely true. The real issue was that the infrastructure was part of the Indonesian national cultural identity campaign, which leaves very little space for other forms of art practice and critical voices. So the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s was the time that many small art initiatives – including ruangrupa, Taring Padi and many others in many places – emerged as a substitute or alternative to state-built art and educational infrastructure. In a different way we are actually always ‘in trouble’. Since the 1998 Reformasi [the period of reform after the toppling of President Suharto] we have very slowly come to a different people–state relation, particularly since many of those small-to-medium initiatives survive and have played an important role in many places and with respect to many of the challenges in Indonesia, now for more than a decade. It is actually a really crucial time to connect these different education and economic models of institutional practice.

As a public institution I think Documenta should really think how it operates and try to find a different economic model, in order not to become centred, extractive and exploitative because of its scale… I think this concern with scale, wanting bigger, greater… it should be obsolete. But I think judging by the current output, many still operate within this logic. People still need that propaganda.

MR Yes, and the state always needs rewards.