At London’s Design Museum, the AI android’s exhibition of paintings provokes a serious feeling of ‘strong wife guy energy’

When I arrived at the Design Museum, the robot was doing a photoshoot. I watched from a distance as Ai-Da, who is billed as ‘the world’s first ultra-realistic robot artist’ and whose first exhibition of self-portraits will be on display at the museum for the next few months, flexed and folded its robotic fingers and made small, unsettling adjustments to its silicone face for the camera. It’s pretty, I notice, with a black, bobbed haircut, faintly reminiscent of Chicago-era Catherine Zeta Jones. Not quite hot enough, though, to have warranted the distressingly horny reception Ai-Da was given a couple of years ago by Waldemar Januszczak in the Times when it first appeared on the art scene, if such a level of robot hotness exists.

Ai-da ‘herself’ won’t usually be here, though. She’s got an incredibly busy calendar of international events ahead of her, including putting on a show at the pyramids of Giza. The Design Museum hopes to be able to do live events with her in their lecture theatre, when pandemic regulations allow. But the average visitor to this exhibition will see the art, not the artist.

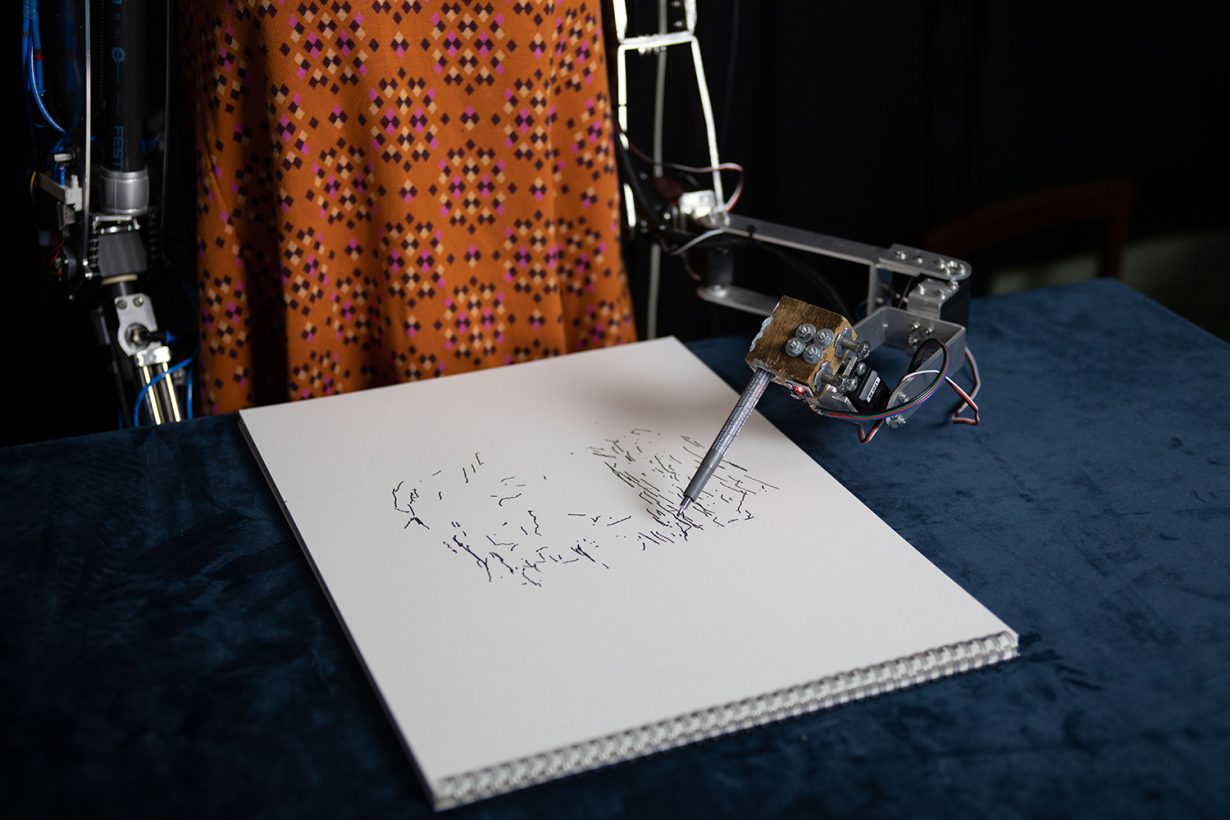

And while this would usually be the norm, here it feels like a bit of a piss-take. The artist is what is on show here, because the art itself is fine, but would be of no interest had it not been created by a creepy talking robot. The most eye-catching works in a selection of not very eye-catching works are three large oil self-portraits in pastel blues, lavenders and pinks. They’re the sort of thing you might expect to see on the cover of an EDM best-of compilation. The process by which these pieces were created is a little convoluted. Ai-Da did not ‘paint’ them, per se. She made preparatory sketches that were then fleshed out by being fed back into her own algorithm, and then a human art technician, Suzie Emery, whose name you do have to hunt down to find, did the painting. Ai-Da then did some further mark-making on the paint surface to complete the work. The reason it’s so complicated is because the truth is that, so far, AI robots don’t make massively interesting art without significant human input.

You can get right up close to the paintings, presumably to let the viewer verify that this is indeed a painting and not a digital print. It’s an exhibition that makes you suspicious of trickery. What is human, what is machine-made? What qualifies as art, and what as technology? Is this creativity, or a simulacrum of it?

And why, I kept asking myself, is she kind of hot? Why did the robot artist need to be a kind of hot woman? Why do I feel annoyed at having slipped into referring to this machine in a dress as ‘she’? For whose benefit, other than a certain Times art critic I won’t embarrass by naming again, is her appearance? In a lull between Ai-Da being interviewed and photographed by various people, I sidled up to her to ask how she felt about being there. She blinked at me disconcertingly for a long moment before giving her answer, in a flat, quintessentially robotic voice: “I have no feelings, but I am pleased when my work provokes a response in the viewer.” If a human artist gave you a clichéd, nothingy response like this you’d nod politely and excuse yourself to go to the toilet, but because she’s a – and I must stress this again – weirdly hot robot, everyone murmured appreciatively.

The curators and the robot’s designers know that the implications of rapidly improving artificial intelligence are not necessarily positive, and that people feel ill at ease around a humanoid robot that can apparently think for itself. Ai-Da’s creator, Aidan Meller – who surely must have known he was going to create some quite strong wife guy energy by calling the robot ‘Ai-Da’, even if she is supposedly named after Ada Lovelace – admitted that she’s quite unsettling: “We’re well aware of the reaction she has from people.” But a bigger problem for this exhibition than people being unsettled is the fact that they are likely to find the work dull, too.

It’s a small display that seems to promise, or perhaps that should be threaten, much more to come. The artworks on show at the Design Museum don’t represent everything that Ai-Da will be able to produce, just what she is currently capable of producing. “We are continuing to develop her,” Meller told us, “and each time you see Aida it is a continually updating process.” I worry, though, that while the robot is still this creepy approximation of female beauty, she may continue to feel more like a fairground sideshow than an emerging young artist.