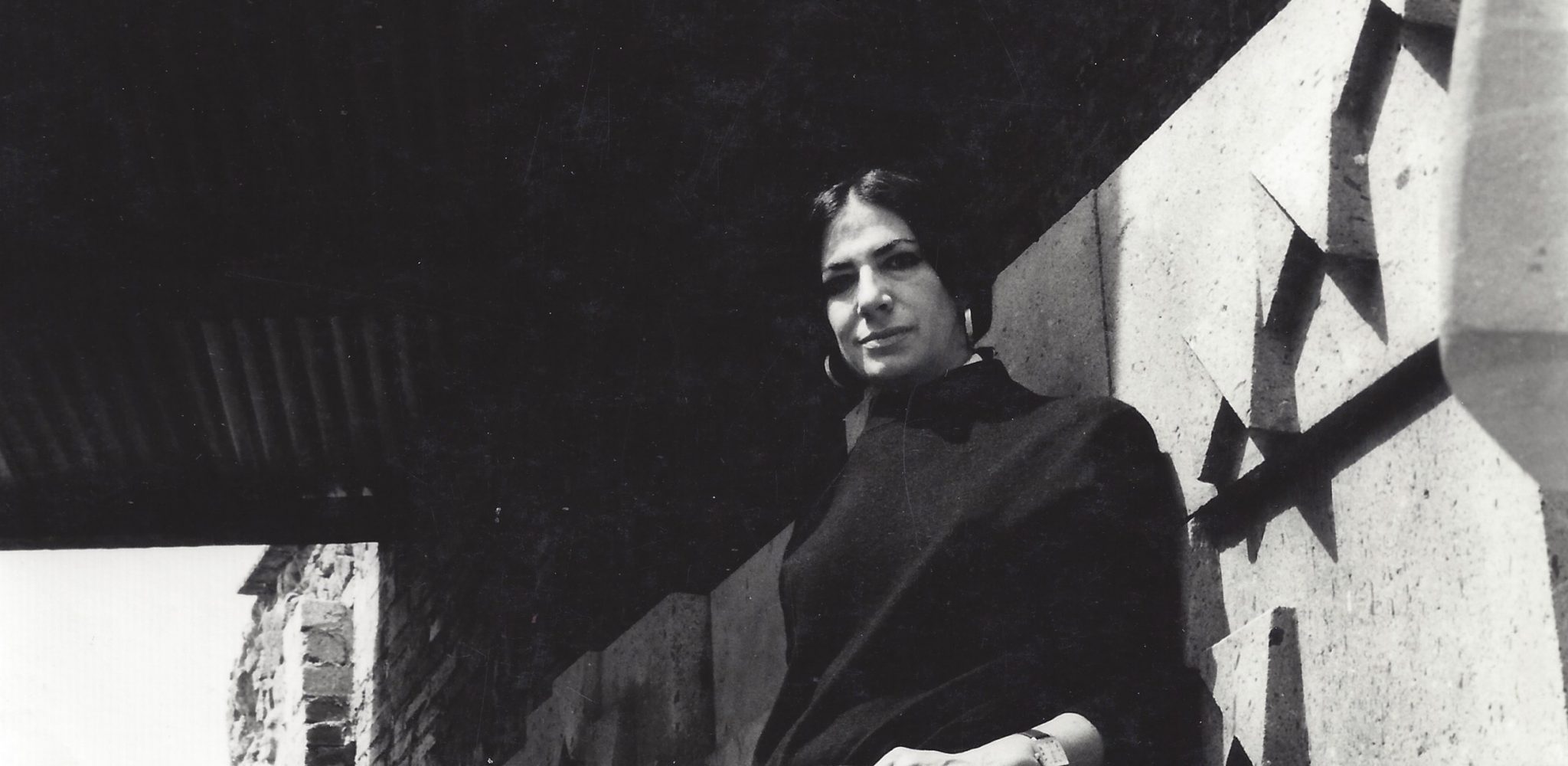

The Mexican sculptor, who turned ninety-two this year, has a deep understanding of the minerals she works with

At the beginning of Ángela Gurría’s long, prolific career sits an episode that would work perfectly as the first act of a feel-good Netflix biopic. The year is 1965. The sculptor, who turned ninety-two this year, is determined to make her mark on Mexico’s sexist society. She wants a shot at public sculpture. She wants to grow her ideas to monumental scale and she knows that to do so she must enter the public competitions in which those commissions are awarded. Women are not welcome, however. It’s an unspoken yet obvious policy at the time, but she decides to go for it nevertheless. Under a male pseudonym, composed of a dear friend’s first name and a last name a letter or two off her own: Alberto Urrías. Urrías/Gurría wins the first prize. The jury is disgusted but acquiescent when she reveals her subterfuge. But she goes on to create La Familia Obrera (The Working Family, 1965), a four-metre-high bronze sculpture installed at the headquarters of a tobacco company in downtown Mexico City.

Gurría discovered her obsession with transforming materials – especially rocks like limestone, volcanic rock and marble, but also iron, steel, bronze and obsidian – early. She often tells a story about walking around her neighbourhood in Mexico City as a kid and hearing stonemasons pounding rocks; it was the rhythm of the constant movement, the sound and its reverberations, that she believes seduced her into pursuing sculpture as a practice. As an occasional music composer, Gurría is very sensitive to sound and rhythm; it still lures her and continues to fuel a curiosity for new materials in all kinds of sizes. She also credits Geles Cabrera, often recognised as the first professional Mexican sculptor, with inspiring her to pursue an art career seriously, having witnessed what a woman could achieve by collaborating with rocks.

Still, Gurría occupies an awkward historiographical space. She isn’t really included in the Generación de la Ruptura (Breakaway Generation), who departed from Mexican muralism during the 1950s, although she is considered to be one of the pioneers of abstract sculpture in Mexico; and even though she worked with Helen Escobedo and Sebastián occasionally, she wasn’t really counted in the notable movements of which they were a part, like Arte Otro or the Salón Independiente – though she did participate in the latter’s first show in 1968. Yet she is also one of very few women artists mentioned when the story of twentieth-century Mexican sculpture gets told, alongside Escobedo, Cabrera and María Lagunes.

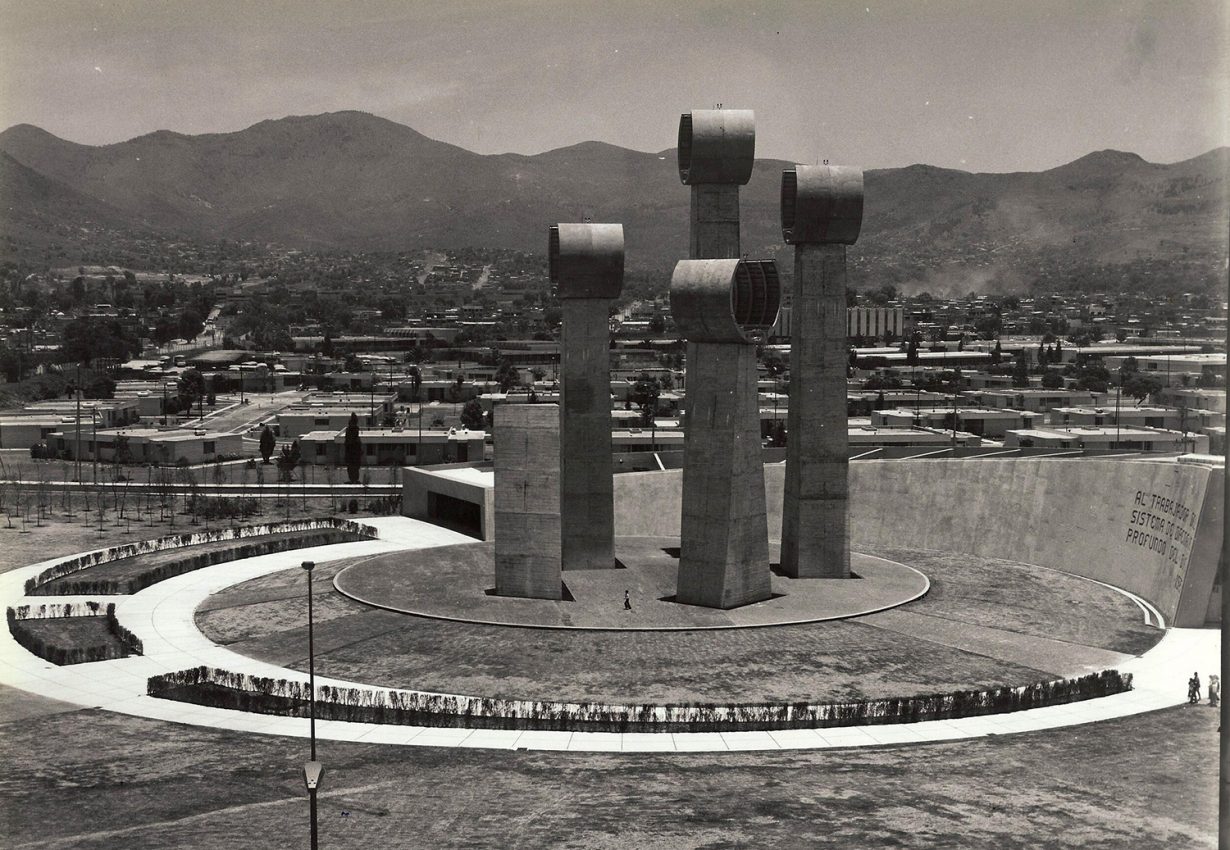

All of these last (and Gurría) make appearances – along with Rosa Castillo and Elizabeth Catlett – in Monumental (2020), an ambitious exhibition at Museo de Arte Moderno (MAM), curated by artist Pedro Reyes, in which he delineates prevailing influences among modernist Mexican sculptors, most prominently: pre-Hispanic art, Land art and geometry. Indeed, in recent years, Reyes has taken it upon himself to proselytise for the works of that particular generation – starting a movement to save the view around the Espacio Escultórico at UNAM’s campus, promoting Cabrera’s mostly forgotten practice – with all of it culminating in the massive exhibition at MAM in which a narrative, centred around the figure of painter and sculptor Mathias Goeritz, about the meeting point of abstract art and public sculpture, was fully materialised. Reyes, after all, spent several years earlier in his career organising exhibitions and creating works at La Torre de los Vientos (The Wind Tower, 1968), a massive Gonzalo Fonseca sculpture that was part of La Ruta de la Amistad (The Route of Friendship, 1968), an impressive project that lined 17km of Mexico City landscape with 19 monumental public sculptures designed by artists from every continent as a welcome to international visitors to the 1968 Olympic Games, and in which Escobedo and Gurría were the only two women artists to participate.

Gurría’s Señales (Signs, 1968), standing at 18m tall, consists of twin concrete structures, one white and one black, that look as if the two halves of a parabola have been broken off and then placed next to each other. Their heavy rectangular bases ground the tall, slender arms that gracefully curve and point towards the sky. Since their creation, the group of sculptures in the project has often fallen into disrepair: fortunes have waxed and waned, and their upkeep is handled today by wealthy families and corporate structures like the History Channel and American Express. Gurría’s, however, was moved when it got in the way of stubborn urban planning.

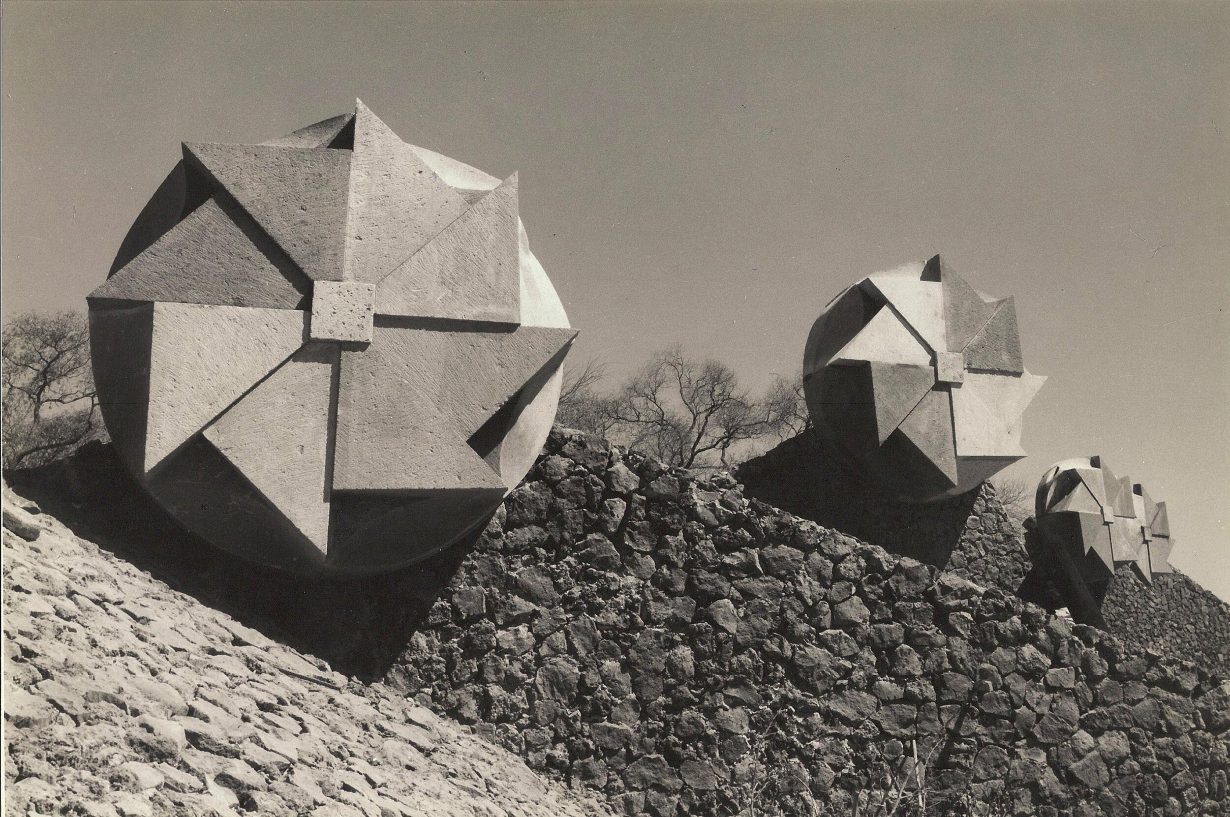

Some years later, a more cursed fate awaited GUCADIGOSE’s first largescale public project. The group’s name comprised two initial letters of each of the last names of its members – Gurría, Cabrera, (Juan Luis) Díaz, Goeritz and Sebastián. In 1976 they were commissioned by then president Luis Echeverría to build sculptures to adorn an urban-modernisation project in the southern Mexican state of Tabasco. Each artist would design a monument inspired by the simplicity and geometry of a nearby Mayan archaeological site, Comalcalco, taking into account the natural elements surrounding each of their chosen locations. Gurría created El Caracol (The Conch, 1976), a circular base with a spiral ramp that arrived at the top, covered in red bricks and located at a traffic circle close to what was then called the Museo de Tabasco. As the story goes, its location doomed it. The museum’s founder, famed poet and politician Carlos Pellicer, was said to have disliked the structure for blocking the facade of his beloved institution; he had it destroyed as soon as Echeverría’s term as president ended, in 1978. Gurría’s was the first of the five commissioned sculptures to be demolished; Goeritz’s was the last to be taken down, in 2008.

Even as these visible – and perhaps a little thankless – collective experiences punctuate her career, Gurría states today that she never really felt part of an artistic community. If her work serves as any indication, one could argue that her true communion (in the sense of mental and spiritual exchange) occurred exclusively between her and the materials that surrounded her. As she put it: “Some rocks don’t like me and I can feel that, but others open themselves, they want me, they help me… and something comes out of me, but it’s them who are giving it to me. How many forms do we hold inside of us? How many interior curves, coinciding with another curve already existing within a rock?… It’s so precise.” This sense of a material call is especially obvious in her marble pieces, such as Nube (Cloud, 1973), in which Gurría seems to follow commands from the rock, ceding her own agency in recognition of what a pattern, a vein, a crack or a crevice is suggesting. The work is a huge rectangle of irregular greyish-white marble, and the seams of the rock appear to be barely altered by Gurría – a few wavy lines following the rock’s veins create the kind of cloudy horizon one can see out airplane windows, the effect of softness and ethereal movement eloquently acted out by the stone-cold slab.

Some rocks (of limestone, for example) seem more cooperative, more willing to bend to Gurría’s wishes. This is the case with Calavera (Skull, 1993), a sculpture in which the simplest lines and gestures describe a human skull, a symbol of death: a clean inverted vase silhouette, two eye-holes carved at the top, a line going through the middle accentuating that a crack at the top has matter-of-factly interrupted the symmetry. Gurría’s ease at achieving synthesis of form, her skill at evoking natural elements in the most economic of terms, is a testament to her deep understanding of the minerals she works with. This insight chimes with what British anthropologist Tim Ingold describes in a 2007 text, ‘Materials Against Materiality’: ‘the properties of materials [are not fixed] but are rather processual and relational. They are neither objectively determined nor subjectively imagined but practically experienced.’ It is in this practical experience, in this decades-long hands-on process with materials, that Gurría seems to have forged the most informing and valuable relationship for her art.

Her work is often described in terms of opposites, life versus death, natural versus industrial, light versus dark, but I would argue the contrary: her art is an attempt at creating a world that is unified, beyond the binaries of human versus nonhuman, natural versus artificial, landscape versus edifice, alive versus inert. She doesn’t claim to bring materials to life through some kind of artistic miracle; she is simply able to know and interpret the life already within them to find them a form, a place and a character that is readable for the rest of us.

There’s another episode in Gurría’s history that’s made for a biopic: the first artwork she ever sold (when she was a teenager) was a song. Indeed, another of her occasional compositions, El día que me dijiste (The Day You Told Me, 1963), was famously performed by ranchera music legend Chavela Vargas. Fittingly it is a love song about stars confusing their night sky home for the darkness of one’s heartbreak. A song about humans being home to the beauty of the stars.

Work by Ángela Gurría is on show at Proyectos Monclova, Mexico City, 19 June – 21 August, and is included in Monumental. Dimensión pública de la escultura. 1927–1979 at Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City, through 3 December

Gaby Cepeda is an independent curator and writer based in Mexico City