What should have been Bong’s victory lap becomes, instead, a too-late warning from history. But one thing remains true: read the small print

In Bong Joon-ho’s new sci-fi satire Mickey 17, Robert Pattinson plays a loveable doofus. Is it much of a stretch for Robert Pattinson to play a loveable doofus? Consider the fact that in a Guardian interview in 2019, he described his experience of life by recalling a passage in a book where ‘there’s, like, a dog in an elevator, and every time the doors open there’s this whole new world, and it just can’t figure out what’s going on’. Once, he said on live television that he’d watched a clown perish in a fiery car wreck at the circus as a child, only to later reveal that he had made the story up on the spot. Per the New York Times, he has recently been working on a design for a chair, having fashioned a maquette out of ‘a Fleshlight sex toy and an empty toilet paper roll’. Timothée Chalamet might done a very funny bit of circa-2003 Bob Dylan cosplay for the premiere of the Dylan biopic he starred in, A Complete Unknown (2024), but he still earnestly proclaimed himself to be “in pursuit of greatness” when he accepted a SAG award last month. What Pattinson is pursuing is, by contrast, a little more mysterious. On the one hand, he has spent the last decade-and-a-half putting in excellent work for some of the best directors in the game. On the other, it is clear that the media training he was allegedly forced to undergo while filming Twilight did not leave a lasting impression. It is as if once he had completed his entrée into Hollywood as a glittering vampire, he elected to sacrifice that version of himself so that two new Roberts could appear in its place: one who is evidently one of the most thrillingly original screen actors of his generation, and another who is something of – excuse my French – a fucking lunatic.

This mental picture aside, it is hard to imagine there being more than one of him on earth, which might help to explain why Mickey 17 – in which there are, yes, two Robert Pattinsons, and in which there have in the past been many more – takes place in space. He plays Mickey Barnes, a hapless Jerry-Lewis-accented galoot who signs up to be an ‘expendable’ on a galactic mission – failing, in his haste, to read the fine print on his contract. Mickey, as so many of us do, needs money; he also needs to, as they say, get out of dodge, and there are few destinations that are further out of dodge than an entirely different planet. As it turns out, his new job is to die – not just once, but many times, often horribly. He is a human canary in the coalmine of the stars, and his expendability becomes (because this is a film by Bong Joon-ho) a metaphor for the body-breaking, soul-crushing monotony and waste of worker exploitation under capitalism. Frozen, burned and gassed on a loop, he is shown in a long pre-title montage – arguably the film’s best and funniest sequence – repeatedly accepting his fate with the grim, darkly humorous resignation of a prehistoric bird being used as a toothbrush on The Flintstones.

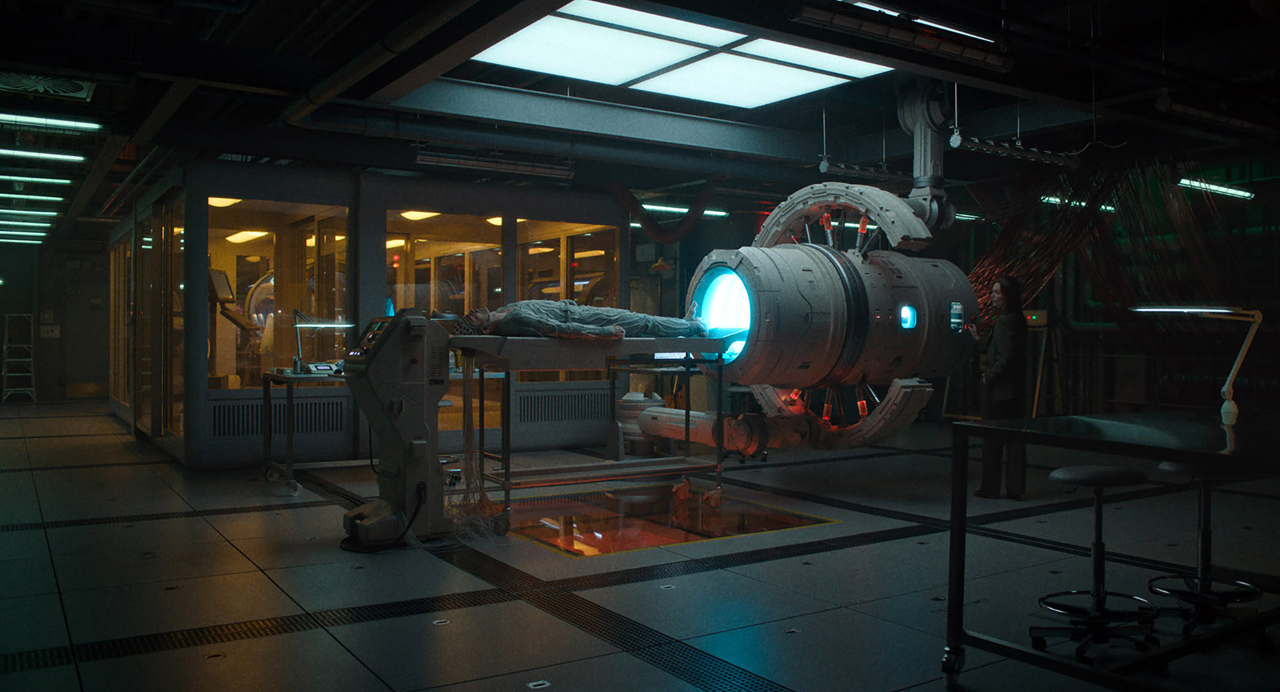

After each expiry, he is reproduced anew with the aid of a slippery, juddering human printer, sometimes sliding to the floor unattended like a document fluttering from an inkjet. The first Mickey we meet is the Mickey 17 of the film’s title, left for dead on a planet made of ice. Complications, as they tend to do in fables about cloning, soon arise: when Mickey 17 makes it back to the ship against the odds, he is stunned to find another new Mickey has been printed to replace him. ‘Multiples’, per the film’s internal vernacular, are strictly illegal, and if those in charge of the ship find that there are now two Mickeys, one will be thrown in an incinerator. Bong and Pattinson, in tandem, make the clones distinct from one another, adding yet another ethical and scientific complication to the Expendable programme: if the copies are not totally alike, what exactly separates all these sequential deaths from murder? Mickey 18 is jut-jawed and intense; Mickey 17 is, as previously cited, an adorable goof. In other words, they themselves somewhat resemble the two sides of Pattinson’s image. A further metatextual layer is added by the audience’s knowledge that in 2018, the actor played the lead in Claire Denis’s High Life, also a bleakly metaphorical film set on a spaceship, in which Pattinson’s exiled criminal Monte was another kind of expendable man – an incarcerated one, fated to die on the mission, being unwillingly used as a stud for procreation in a prison experiment from hell.

Squint a little at the two Mickeys, and it is as if Monte and Mickey 17’s himbo hero had been placed side-by-side, the result a collapsing of Pattinsonian selves that hints at his ability to be an everyman by playing, paradoxically, any kind of man you ask him to. Either way, his everymen often end up getting fucked. High Life’s satire is aimed at carceral cruelty; like Mickey 17, it is a pointed criticism of America and its values made by a non-American, and it uses broad strokes in lieu of subtle shading to ensure the audience gets its point. Helming the exploratory trip on Mickey’s spaceship is a tanned, puffy bigot named Kenneth Marshall (Mark Ruffalo), an incompetent and pompous politician who dreams of escaping a dying and impoverished earth to create a new “pure, white” planet. The word “white”, in Marshall’s pouting mouth, becomes an interesting bit of doublespeak: he is referring to the snow on the ground, but we are left in no doubt as to what he really means. Shoring up his hateful rhetoric with religious values, selling red baseball caps to his fans, it is so obvious who he is standing in for that it’s hard to decide whether this obviousness is self-defeating, or genuinely bracing. Originally intended for a 2022 release, Mickey 17 was made at a time when it seemed impossible that Trump would be elected for a second term, which may be why there are repeated references to Marshall’s two-time defeat – what should have been Bong’s victory lap becomes, instead, a too-late warning from history.

Spoofing a real-life figure who is as simultaneously cruel and absurd as the current US President is tricky, since almost nothing that’s invented can beat what is actually happening in the news, and it is harder to laugh at the idea of a warmongering white supremacist when there is one in office, poised to throw everyone who does not look and think exactly like him straight into the proverbial incinerator. Of the film’s central plot involving the attempted takeover of a planet of hyper-cute bugs, which culminates in a heartfelt, expletive-strewn speech about how it is us, and not them, who are the alien invaders, there is not much to say on a critical level, largely because the film’s position on the matter is so utterly correct that all one can really do is nod along. To all this, there is an air of the exchange that the comedian Stewart Lee famously acts out between two of his fans: “Did you see Stewart Lee?” “Yeah.” “Was it funny?” “No, but I agreed the fuck out of it.” Do I think Mickey 17 is making any new points per se about capitalism, Trumpism, anti-immigration, colonialism, or the evils of genocide? No, but I agreed the fuck out of it. Those chittering, low-slung bugs are every bit as loveable as their cinematic ancestor, Okja, from Bong Joon-ho’s previous English-language feature of the same name (2017); the film’s politics are every bit as right-on as the politics of his Oscar-winning Parasite (2019). In fact, Mickey 17 as a whole is, somewhat miraculously given its heavy subject matter, fun. It is silly when it needs to be and tense when it needs to be, too, and carried along by the Keatonesque physical comedy Pattinson performs as the softer, sweeter Mickey.

Back, then, to one of the more esoteric pleasures of Mickey 17, which is the way that its theme of replication plays out in concert with the image of its star. Acting itself is a job, but audiences are quick to roll their eyes when those who do it for a living make complaints. They are, after all, well-compensated, usually fantastically good-looking, and paid to make their art. The exploited expendable, with his cyclical deaths and his status as a living indicator of suffering, might seem on the surface to have very little in common with the Hollywood A-Lister, who is often regarded as more than, a singular figure who cannot be replaced. And yet: don’t A-Listers age out of their jobs every year? Doesn’t a newer model usually spring up in their wake? In a sense, too, performing itself requires a kind of bodily splitting: what is acting but printing a new version of yourself, and then discarding it once the job is done? When dismissing an actor out of hand, critics often talk of an actor ‘playing himself’. I find it hard to remember the last time I saw Robert Pattinson using his own accent or his own mannerisms in a film – he is easiest to remember as an icy billionaire stockbroker, an all-American greaseball, a lizardlike preacher, a Dauphin in a wig. Perhaps his apparently bonkers persona offscreen is authentic, or perhaps it is a very smart distraction or a decoy. If we can’t get a hold on exactly who he is or what he wants, how can we know which of his selves is the real one?

Philippa Snow is a writer based in Norfolk. Her latest book is Trophy Lives: On the Celebrity as an Art Object (2024)