And is the real truth that it is as innocuous as it is important?

On Saturday 23 July, an event broadcast live from an echoing hall at Documenta 15 brought two Thai nonprofit groups together for two hours of dialogue. Members and friends of the Thalay Association, an independent platform promoting and supporting Thai society abroad, particularly in Europe, joined Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts & Culture, an artist-run initiative from Thailand’s Ratchaburi province, for Churning Politics.

And churn – in the stir-the-pot sense of the word – they did. Conducted mostly in English, the talk staged at Baan Noorg’s Documenta contribution – a three-part installation centred around a dairy farm exchange-programme, displays of nang yai (Thai shadow puppetry) and a skateboard ramp – used an intertextual approach to accessibly trace Thai crises through the arts. Bookending the guest speeches and frank discussions on patriarchy, state persecution of youth activists, Article 112 (the country’s morally repugnant lèse-majesté law) and the history of popular protest in the country was the host’s invocation of the Ramayana. Allegorical links were drawn between the Hindu-Buddhist epic’s narrative arc, which sees the cosmic forces of good crushing evil, and the semi-feudal power structures and hierarchies that prevail in the nation as of mid-2022. “The Ramayana is one of the ideas used to support the monarchy system,” explained Baan Noorg cofounder Jiradej Meemalai.

For those sitting cross-legged on the floor, ambling through the room or watching online (as I was), the event was a discursive introduction to Thai sociopolitics spectacularised by both the graffiti tags on the skate ramp (khon taow gun – ‘we are all the same’ – says one) and the shadow puppets arrayed along one wall. But the event was also more than that: its collaborative dynamics arguably an illustrative proxy for the collective spirit at play in the country’s art scene and all it now touches.

Firstly, there was the character of the hosts. While artist collectives in, say, the Philippines or Indonesia are often alliances or fellowships with equitable power dynamics between members, the Thai equivalent are “houses of friends where people come and go”, as independent curator Vipash Purichanont puts it. Baan Noorg is of this accommodating, if carefully maintained and somewhat impervious, build. Since founding it in 2011, Jiradej and his wife, Pornpilai Meemalai – a multidisciplinary artist duo known as jiandyin – have worked with many collaborators across myriad disciplines and regions, including Taiwan and Nong Pho, the rural subdistrict in Thailand’s Ratchaburi province where they are based. But each community-orientated Baan Noorg project – their room at Documenta featuring input from a clutch of invited project members being the latest example – is activated by them, not the mercurial output of a horizontal ‘collective’ devoid of hierarchy.

Secondly, there was the discussion’s polemical tone. A conviviality and sanguine introduction (“The expected outcome is to find out the possibility of living together and achieving better community,” declared the excitable host) quickly faded to reveal the ideological ruptures and acrimony that have, in recent years, cleaved Thai civil society into binary groups of warring factions: Red and Yellow, phrai (commoner) and ammat (aristocracy), sam-kib (three-finger-saluting pro-reform protesters) and salim (pro-regime conservatives), democracy and dictatorship. And it was clear, in listening to the strident left-of-centre perspectives, where allegiances lay. Rightly or wrongly, us-versus-them is the default position in critical art discourses in the country – exhibitions or events where opposing camps engage are almost nonexistent.

Thirdly, the event’s analysis of the oppressive mechanisms of one form of state power was, as part of Documenta 15, facilitated and smoothed by another form: German largesse (in the guise of the city of Kassel, the state of Hesse and the German Federal Cultural Foundation). In recent years, agonistic artists, groups and curators within Thailand, where government support for the arts and grassroots civil-society is scant, have increasingly looked to tap grants and relief funds from foreign sources. Some of these financial lifelines are hush-hush; others are paraded publicly in the belief that they offer a kind of protection.

Tugging any one of these threads would lead you closer to the genealogical roots of Thai art activism, socially engaged practices and critical exhibition-making, but fringe activities at Baan Noorg’s Documenta outing offer just one entry point into collectives and collective work in the country. Back in Thailand, for example, a trend for archiving and contextualising the latest street-protest movement – as though it were a movement singular in Thai modern history for the audacious breadth of its taboo demands – through exhibitions of protest objects has emerged.

Museum of Popular History (2021) is one such collection of protest artefacts – everything from banners to wirecutters, whistles and hand-clappers – spanning from 1932, the year the Khana Ratsadon (People’s Party) revolt brought an end to absolute monarchy, through to the youth-driven 2020–21 Ratsadon protests. The archive, run by young historian Anon Chawalawan, an employee at iLaw, an NGO promoting public participation in social and legislative reform, first appeared at Bangkok CityCity Gallery during the space’s Art Book Fair last December, then a new Bangkok gallery, Kinjai Contemporary, in March. Meanwhile, Cartel Artspace, a nonprofit project space at Bangkok’s N22 complex run by dissident painter Mit Jai Inn, has put on two shows in recent months. The Battle Wound of Thalufah! (2022) featured artefacts belonging to Ratsadon-affiliate group Thalufah, while #Post 2010 (2022) presented photojournalist Karnt Thassanaphak’s documentation of protests from the 2010 Red Shirt movement onwards.

It could be argued that the valorisation of protest ephemera as art is a regressive development: participatory and relational aesthetics – so integral to the story of Thai contemporary art and the practices of prominent internationally established Thai art-scene figures such as Rirkrit Tiravanija and Surasi Kusolwong – seek to bring everyday life and relationships into the gallery, not decontextualise the quotidian object. And inanimate agitprop and protective gear hung on clean white walls is a pale imitation for the sensorial overload of a street- protest movement, especially one that so dynamically deployed caricatures, sarcasm, cartoons, graffiti, placards, fashion shows, live theatre and music performances. Yet the trend speaks of a widely felt urge to periodise a chapter of collectivity that may otherwise be lost or erased… as so much brutal modern history has been.

The art scene’s commitment to indexing protest also makes sense when you trace, as art historians such as Claire Veal and Seng Yu Jin have done, critical exhibition-making and collective art practices in Thailand back to their leftist origins.

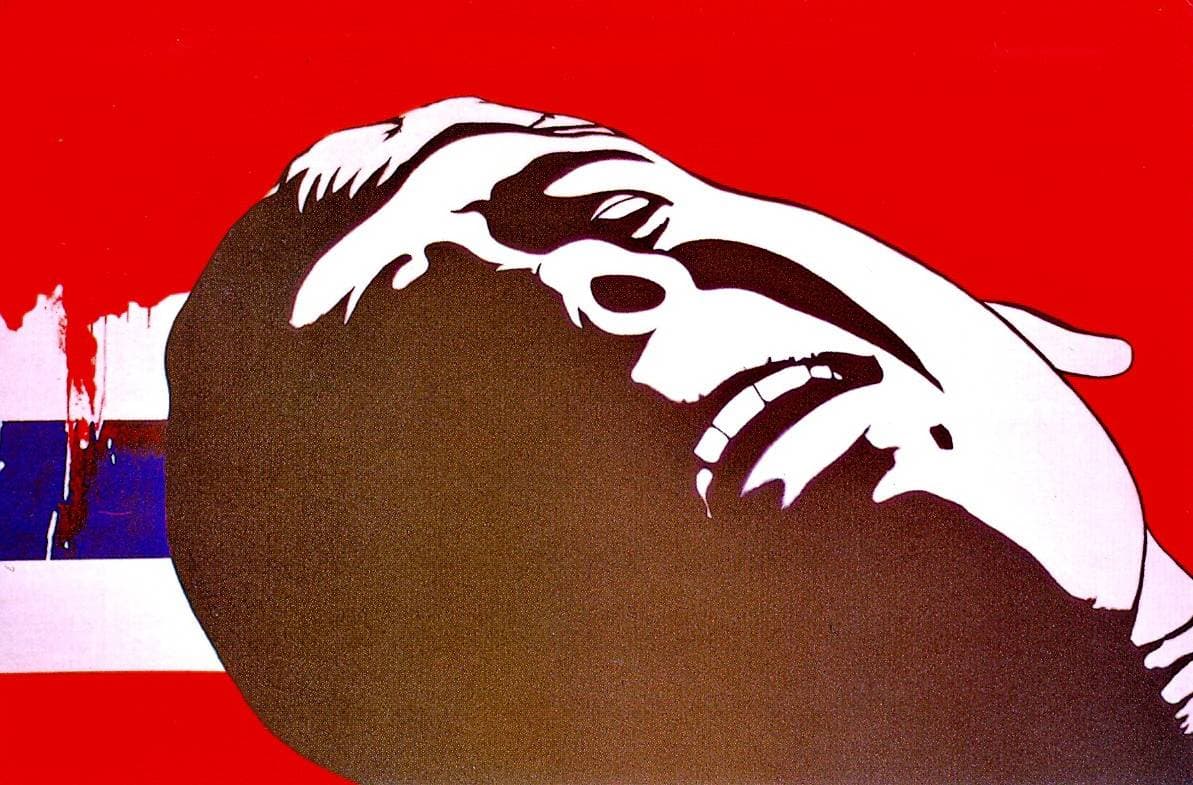

Out of the student-led Bangkok uprising of 1973 sprung radical artist-groups who used modernist idioms to articulate anger at authoritarian rule. When the 14 October 1973 protest led to the collapse of Thanom Kittikachorn’s anticommunist military dictatorship, but left 77 student and civilian demonstrators dead, a nascent collective comprising pacifist Buddhist artists, the Dharma Group, responded.

For an exhibition shortly after the brutal massacre, its leader, Pratuang Emjaroen, produced The Days of Disaster (1973–74), a transcendent six-metre-long oil painting stippled with bruising iconography: frightened faces; a crushed Dhamma wheel; the face of Buddha pocked with bullet holes. Another fantasy space, Red Morning Glory and Rotten Gun (1976) – in the collection of the National Gallery Singapore – renounces the actions of the military and its betrayal of Buddhism by depicting a pair of biomorphic rifles oozing blood, pus and maggots near a decapitated Buddha statue.

In October 1974 another group, the Artists’ Front of Thailand, commemorated the student’s victory a year earlier with a display of over a thousand paintings and posters strewn along the city’s prestigious Ratchadamnoen Avenue. And in October 1975, a group calling themselves the Coalition of Thai Artists presented ‘people’s art’ and banners along Ratchadamnoen Avenue – a symbolic gesture of democracy and reaction against the bombing of Vietnam by American military based on Thai soil.

Such artists’ groups were part of a larger, ground-up ‘Art For Life’ movement that spanned music and theatre as well as art, and which drew ideological guidance and inspiration from earlier Thai socialist discourse, such as Marxist historian Jit Phumisak’s Art for Life and Art for the People (1957). This blooming of democratic free expression withered, however, when the student and civilian massacre of 6 October 1976 heralded the return of dictatorship, leading many radicals to flee to the jungle. The modernist grounding of many ‘October Generation’ artists, meanwhile, particularly their working in Surrealism and Expressionism – styles largely accepted by the establishment – led to some of their membership being easily reabsorbed into official arts systems during the 1980s. The aims of these groups were also, as Veal writes, ‘filtered through a populist, though not self-conscious, nationalist idiom’.

Today, the influence of these groups is evinced not just by the symbolic use of sites such as Rachadamnoen, Thammasat University and the Democracy Monument in contemporary protests. More pivotally to the art scene, the artistic strategies they deployed to subvert the ideologically conservative, Silpakorn University-dominated gallery system and better integrate artistic practice with practical, political concerns – such as social engagement, the conceptual and the manifesto – have been a feature of many an artist-initiated group, event or space since.

Notable in this regard were experimental art festival Wethi-Samai and Chiang Mai artist and activist co-op Tap Root Society, both founded by performance artist Chumpon Apisuk during the late 1980s. A decade later, nonprofit spaces like Project 304 and About Café, as well as events like the Bangkok edition of Hans Ulrich Obrist and Hou Hanru’s travelling exhibition Cities on the Move (1997–99), performance art festival Asiatopia (also founded by Apisuk) and Womanifesto – a biennial hosted in Thailand that, during a decade- plus of spirited activity, gave a much-needed platform to women artists and women’s themes – began to spur new modes of globally networked cultural work.

Yet most of these groupings struggled to achieve longevity or consistency, or never aspired to. While in Indonesia, socially embedded concepts such as sanggar (creative communities) ‘prepared’, as noted by artist and writer Elly Kent, ‘the climate for the abiding importance of dual attention to collectivity and the individual in Indonesian art’, horizontal systems of mutual cooperation within Thailand – such as long khaek (the tradition of labour sharing among rice farmers in the northeast) – appear not to have had an analogous symbolic or structural impact. Why this is the case is a question for future art-historians, although scant funding is clearly a constant barrier. In some cases, the fleeting artists’ initiative may well have been a response to local needs, a strategy designed to suit the ecosystem in which it existed.

Some observers have also hypothesised that collective impulses or tendencies are routinely superseded by private concerns, such as the unforgiving schedule or careerism of the internationally mobile artist or curator. Or egos. “I’ve been thinking about this for many years: why no one wants to work together – like really commit and move forwards together,” says Penwadee Nophaket Manont, a curator focused on multidisciplinary community and civil-society engagements. “We are too individualistic. People often expect benefits from being together.”

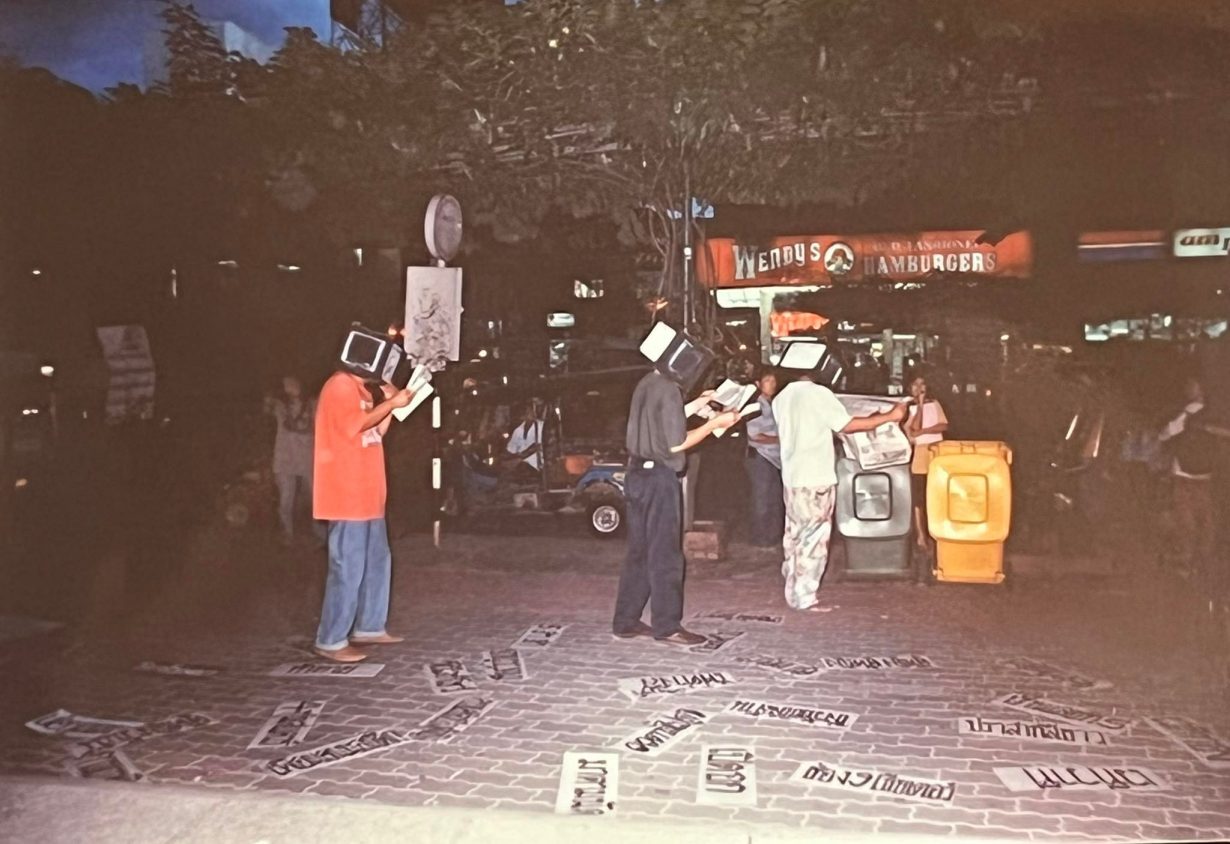

Others have speculated that artist-led events and initiatives have often been ideologically thin or fragile. In the book Artist-to-Artist: Independent Art Festivals in Chiang Mai 1992–1998 (2018), the Thai-Indian artist Navin Rawanchaikul recalls Chiang Mai Social Installation – a much-mythologised artist-led street festival series strongly informed by Joseph Beuys’s concept of social sculpture – becoming ‘more like a party or a get-together than a social intervention’ in its chaotic final years. Another artist with a praxis centred on community art, Jay Koh, complains that the organiser’s ‘critical position had no cohering value’ and the festival at large ‘no continuum’.

Reflecting in 2019 on the underground Thai art movement of the 1990s and 2000s, one of the principal figures in the Thai art-activism scene – the late curator-critic Thanom Chapakdee – stated that ‘there was not really a strong sense of ideology of an art resistance. We just joined in for the pleasure of doing activities and exhibiting together in the public arena. Deep down no one was really talking about how we could go against mainstream culture or what was happening politically.’

Chapakdee, who passed away suddenly on 27 June, was speaking from first-hand experience. During the mid-1980s, the Ruang Pung Art Community – an avant-garde space at Bangkok’s Chatuchak Weekend Market free from official or government influence that drew artists, musicians, cultural activists and art lovers – spurred the emergence of several collectives. With strong ties to a vibrant civil society and thriving NGO sector, these motley groups ‘afforded their members a place to learn from each other outside of institutional structures, providing a forum for collective action,’ as Koh later recalled. They included Ukabat, a public protest-art and blues-music collective consisting of, among others, the visual artist Vasan Sitthiket, performance art duo the Plienbangchang Brothers and Chapakdee.

In his version of events, art-activist groups like Ukabat bonded around a spirit of ‘Thainess’ that appealed to and assuaged the anti-capitalist, anti-IMF and antiglobalisation instincts of members but did nothing to address society’s structural deficiencies and injustices. Members were aware of this moral slippage or shortfall but didn’t address it in the interests of preservation, out of a fear that an internal struggle of ideas would split the group – which is what eventually happened. ‘When the political climate grew more and more tense between right wing and left wing, yellow shirts and red shirts, artists started taking sides and the whole scene split into two,’ he recalled.

For Veal, the emergence of this split in around 2010 was a watershed moment for Thai art as well as politics, corresponding with the expansion of ‘the Thai social imaginary associated with the contemporary turn’. Innovations like the online circulation of images and videos and the use of street-art strategies ‘shifted understandings of collectivity as well as the aesthetic structures used to trace or facilitate the collective’. Writing in 2012, she posited that these new imaginative constructions and articulations of collective identity were distinct for their ‘temporary, network-like structure’ and ‘strategic expansion beyond national boundaries’.

This shift from a modernist collective form to a contemporary post-national form has only accelerated in the hyperconnected present. Throughout 2020, just as the COVID-19 prevention restrictions and emergency decrees began to bite, hundreds of anti-government protests erupted. The first wave, in Bangkok schools, colleges and universities, was student-led and triggered by the Constitutional Court’s dissolution of a progressive political party supported by many young voters, the Future Forward Party. But subsequent waves saw a much broader coalition of activist groups all over the country coalesce around a laundry list of gripes and goals.

This rhizomatic ‘mob’ movement was unique in history both for its aims – fresh elections, a new constitution, abolition of the military-appointed Senate and a restriction of both royal prerogative and lèse-majesté laws – and its methods. Street protests, flash mobs and sit-ins were fluidly mobilised via Twitter, and the imagination of a global as well as local public captured by the strategic deployment of pop culture. The #LetsRunHamtaro protest on 26 July 2020, for example, drew young activists dressed as the Japanese manga hamster Hamtaro to the capital’s Democracy Monument (‘The people are like a hamster locked in a cage, a social structure that oppresses and exploits,’ said its leaders). Other forms of culture-jamming and détournement were brainstormed using the hashtag #Mobidea.

These Situationist forms of online and offline action inspired many a visual artist, even as fatigue set in and dreams faded (all of the movement’s demands failed, the proposal to reform the monarchy was ruled seditious and many of its de facto leaders now languish in jail). As during the 1970s, many artists tracked the movement. Some, such as Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Taiki Sakpisit, discreetly documented; others performed. Others still saw, in activist groups such as FreeArts, Human รา้ ย Human Wrong and Thalufah, a reflection of their as-yet-unrealised better selves, detecting forms of collectivity or artmaking they have long admired: a lack of status or pecking order; a retreat from the realm of the object; an engagement with social life both as the site of production and the medium of expression; and a nimble capacity for resource movement and exchanges of all kinds.

In his statement for Project Pry 02 (2022) at Bangkok’s WTF Gallery, a recent exhibition about the movement curated by Penwadee Nophaket Manont, Chapakdee wrote passionately about how the ‘drum roll of Rasadrum’ – a protest-movement percussion group consisting of young activists, many of them women – ‘united with the sounds of commoners joined in the fight against capitalists, warlords, feudalists and dictators who sieged the country since the Siamese revolution of 1932’. For him, these and other forms of artistic presentation were beyond anything official visual artists ever achieved: pure expressions of the democratic, artistic ideal, the ‘Plebian Aesthetics’ and ‘Aesthetics of Resistance’ he had advocated for vociferously in recent years through his cultural activism and Khon Kaen Manifesto art festival up in Isaan, the country’s northeast. ‘May the victorious drums of the common people and artistic practices thrive!’ he signed off.

Today, post-lockdowns, post-protests and post-Chapakdee, the prospects for art activism and collectivism in Thailand are nothing if not precarious. Recent months have seen lawmakers legalise marijuana and draft an anti-torture act, but, in a worrying development, a law bill that could restrict forms of public assembly and allow for closer state scrutiny of civil society organisations and their funding is also in the legislative pipeline. This NPO Bill appears to be less of a looming threat to, say, the nonprofit gallery that taps the budgets and relief funds dispersed by cultural attachés and embassies than it does to, say, the nonprofit human-rights advocacy charity. Although, having said that, the patronage networks supporting a handful of agonistic galleries and events – the likes of WTF and Khon Kaen Manifesto and even Churning Politics – leave them exposed to the very same pro-regime charges that face agonistic facets of civil society: that of collusion with, and co-option by, foreign powers.

Moreover, crossovers between the nonprofit art scene and the wider nonprofit sector are not without risks. Last November, for example, a live painting event in the alley outside WTF ended with the whole area being cordoned off by police. Hosted by the Cross Cultural Foundation, a human rights NGO, the event initially attracted a noise complaint, but the police shut it down after spotting graffiti that they deemed to have crossed the indistinct line imposed by the lèse-majesté law. “We’ve been marked by the authorities. Usually we get someone coming to check each show,” says Somrak Sila, WTF’s well-connected director, of the aftermath of this sorry episode. For her, having the logo of the Goethe-Institut Thailand or some other Western cultural institute or embassy appear prominently on the brochure for each socially engaged project – including Project Pry 02 – is a talisman that helps to ward off state harassment. Back in Europe, the Thalay Assocation recently issued an open letter to the Royal Thai Embassy in Berlin accusing the Thai government of dispatching an undercover agent to film their Baan Noorg forum collaboration at Documenta 15. ‘Upon seeing the man,’ they wrote, ‘we could immediately notice – which every Thai activist would do, too – that his appearance resembled that of Thai soldiers, policemen or undercover government officers, who frequently turn up in disguise at protests or political activities.’

Meanwhile, the glut of temporary, network-like aesthetic structures centred on Thai political activism – theatre performances, satirical memes and publications, as well as exhibitions – is striking. Disorientating, even. On the face of it, these provisional and symbiotic forms of collaborative solidarity appear as innocuous as they are important in respect of basic human rights and crisis response: these are houses of friends where people can safely come and go. But with their owners and guests – not to mention audiences – clearly in league or in sympathy with the emancipatory politics and counter-hegemonic strategies of the latest crushed protest movement, one is often left with a nagging question: how to bring in and accommodate those members of Thai society left on the outside? In that sense, you could argue that their cliquishness and partisanship make them a crude yet useful barometer: this is a question the entire country, not just a loosely networked yet deeply split art scene, seems ill-equipped to answer. For another generation at least.