The multiverse, multiple doppelgängers and meta-crime-capers – this year saw the centre of cinema being pulled apart

Earlier this year, I was sitting in a darkened cinema, waiting for Everything Everywhere All At Once to begin. The only thing I knew about the film going in was that it took the viewer down an endless tunnel of twists and surprises; that anytime you thought the story was going to unfold in a certain way, a new insane storyline would crop up to unseat all your precious and entirely incorrect presumptions. Before the film, there was a trailer for The Lost City, a high-octane adventure-romcom in which Sandra Bullock plays a reclusive author kidnapped by a megalomaniacal billionaire – is there any other kind – and finds an unlikely ally in her Fabio-like book cover model played by Channing Tatum. That was followed by The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent, a hyperreal Nicholas Cage action vehicle in which Nicholas Cage plays a fictionalised version of Nicholas Cage. He gallivants across Mallorca, morosely considering retirement before getting drawn into a kidnapping plot involving the CIA. Interesting, I thought. Then, well into Everything Everywhere, as I watched Harry Shum Jr’s chef howl with violent wounded rage at losing his beloved raccoon (who is the real chef, in a riff on Ratatouille) and a henchman leap in valiant and stupid courage to land his ass on a trophy bearing a striking resemblance to a butt plug (and in doing so, unlocking a new combat ability, like in a video game), it hit me. Like that ubiquitous meme of a cheerful pizza-bearing Donald Glover returning home to find it aflame, I felt like I was witnessing a new stage of cinema: chaotic, wild, vibrantly unstable, with scripts that came from the unplumbed psychic depths of the Freudian iceberg plied with a bottomless supply of cocaine; cinematography that lit the world with a lurid, hyperreal, almost religious fervour.

It continues. Daniel Radcliffe, who played The Lost City’s billionaire, took a star turn in the sleeper hit Weird: The Al Yankovic Story. In the ‘true story’ of the parody artist, he takes on trained assassins, faces Pablo Escobar, and gets with the criminal mastermind known as Madonna. Director Alex Garland, known for the tense and controlled science fiction films Ex Machina (2014) and Annihilation (2018), embraced mess in Men, a horror set in an English village where not only is every man a variation of Rory Kinnear, but is also capable of giving birth to other men resembling Rory Kinnear. In Jordan Peele’s Nope, hell was no longer other people, but rather other beings, celestial and frustratingly set against that all-important cinematic (and increasingly social) imperative to represent oneself on-screen. Off-screen chaos nearly engulfed on-screen chaos in Olivia Wilde’s Don’t Worry Darling. No film could ever quite match the frenzied speculation that preceded it – about the love triangle between the director and the leads; Harry Styles’s acting; which actors bothered to show up to press conferences and which snubbed them in favour of sharing videos of themselves enjoying an Aperol spritz, dressed head-to-toe in Valentino – but an extended scene of Styles maniacally dancing, marionette-like, to a cacophonous brass band gestured to the mood of the season.

What is going on? A clue came when I read Everything Everywhere actor Jamie Lee Curtis’s apparent ‘feud’ with another multiverse-expanding recent release, Dr Strange in the Multiverse of Madness. Over the past decade, everyone in the industry has had to contend with Disney-Marvel’s hold over contemporary cinema. “It’s hard to find an audience these days unless you’re a Marvel movie”, Nicholas Cage wistfully admits in The Unbearable Weight. He himself is working on a film (it’s meta like that) and though initially resistant to introducing a kidnapping plot – it might be too unserious – he relents when told that people need a special hook to get into the cinema. By his CIA handler.

And so, confronted with an ever-higher bar for audiences and earnings, cinema has escalated their weird and wonderful hooks. The current crop of Marvel films first distinguished themselves by popularising a form of superhero film more grounded than their cartoonish 20th-century counterparts, with sardonic wise-guy protagonists, an embrace of scientism (so many gadgets, so many hero-engineers) and heralding of a benevolent wealthy power always there to right the world back on its course. It seems no coincidence that the first of them all, 2008’s Iron Man, arrived just a few months before the election of Barack Obama. It was a time when one could (somewhat) credibly tell the story of an American arms trader/womaniser/billionaire genius developing a conscience, with peace in the Middle East represented by Stark flying over to Afghanistan in his suit to gun down some bad guys, his life lit with an aspirational, gilded sheen. Today you just look at Elon’s tweets and laugh.

It is not just commercial incentives behind this rise of weird cinema. The mood is changing. These films arrive at a time when ‘permacrisis’ is deemed the word of the year and movie stars warn that ‘societal collapse is in the air’. (‘It’s tough to be alive right now’, Timothée Chalamet announced while promoting his film Bones and All at the Venice film festival.) ‘Certain experiences cannot be formulated because they have occurred too soon’, John Berger wrote in his 1972 novel G., referring to the phenomenon when ‘an inherited worldview is unable to contain or resolve certain emotions or intuitions which have been provoked by a new situation’. It is a feeling of being stuck in history; the feeling of wanting to uncover and articulate a new tomorrow, yet being constrained by the vocabulary and structural forces of our time. I have thought about that a lot these past few years, when we’ve seen the collapse of the narrative power behind our current period – identified by Eric Hobsbawm as the neoliberal age that emerged from the 70s, which heralded the rise of unchecked capital and the bootstrap-wearing individual economic triumph – but have yet to see the emergence of the new.

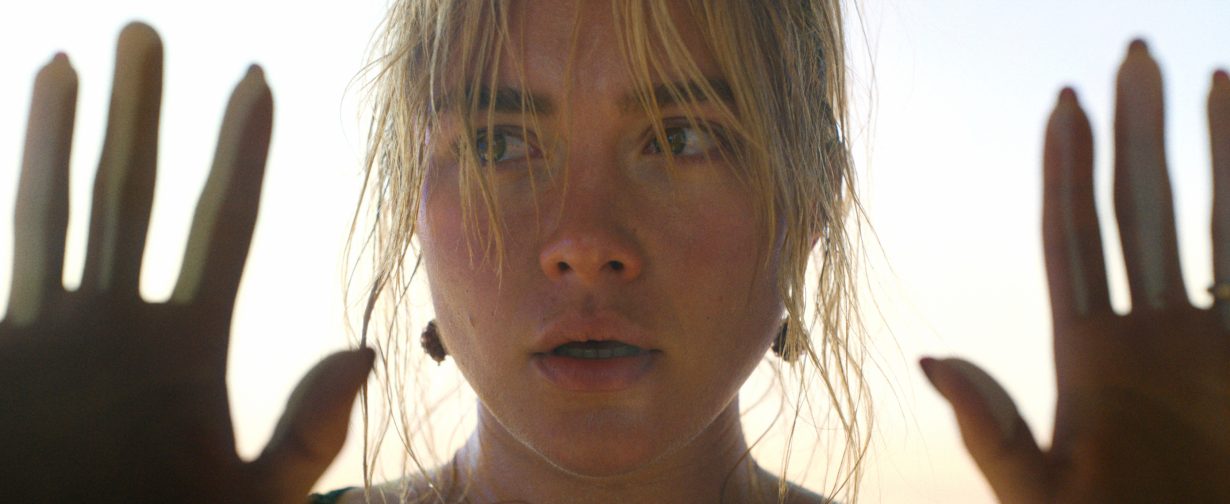

Old promises are broken, their worldviews exposed as empty: everywhere around us are signs of the venality of the rich; the impossibility of advancement in a fundamentally unequal system; the consensus that there ought to be more to life than the endless grind of making yourself a meagre amount of money, and the shareholders a lot. Yet the ascendancy of the monied elite continues unabated; the markets march on at the expense of the planet and ourselves; the need to produce, to consume, to work is unwavering. No wonder contemporary cinema pulses with a chaotic, frenetic energy, pushing at seams of our reality. No wonder there is an almost hilarious incoherence in some of its attempts at a conclusion (the impossibility, as Berger notes, of using the forms of the old world to articulate the new.) The orgiastic spectacle that is Men’s ending – with Rory Kinnear giving birth to a chain of other Kinnear – seems to be a gigantic howl at history’s door. Then, at the end of Don’t Worry Darling, Florence Pugh makes a break out of her Stepford-wife metaverse after a car chase through the bleak and apparently endless desert. It is suggested she is successful; the last scene of the film is of her pushing the glass wall to come out on the other side. Ending the film this way feels like a cop-out. We know what the patriarchy wants of women; what is more interesting is what life looks like after the cage.

Which is not to say these films are about nothing at all. In fact, it is the inability to understand the worth of anything that risks dooming Everything Everywhere’s villain, the omnipotent Jobu Tupaki, to a life within purpose, joy or intimacy. If these films are born out of the chaos of our historical moment, they are also searching for a way out. How does one hold all the impossible features of contemporary life – the proliferation of endless, stupefying information; the fungibility of all things, except apparently tokens; the smallness of ourselves against the terrifying cosmos – Everything Everywhere asks in its depiction of a universe-bending conflict between a mother and daughter, and find within it moments of grace, intimacy and love? Observing the contemporary novel’s move away from ‘the self and its dilemmas’ and towards the possibility of transcendence, the novelist Missouri Williams writes: ‘Perhaps we have realized that we are in a cathedral. Perhaps we are sick of looking at our phones and have begun to examine the ceiling.’ Perhaps a similar thing is happening in cinema. ‘I wrote [the film] trapped inside’, Jordan Peele said of Nope, a film he made while fearing for the future of cinema, ‘and so I knew I wanted to make something that was about the sky’. It looms overhead, cerulean-blue and quietly threatening in his film; siblings OJ and Emerald are determined to capture what is out there. And here we are in our world, living in a moment at once entirely ordinarily and momentous, reaching for the sky, both wondering and fearing what will reach back.