The Indonesian collective aims to work as a double agent: a team of artistic directors for a major exhibition pursuing an activist agenda

While ruangrupa’s international standing has increased dramatically since its appointment as curator of documenta fifteen in early 2019 (the exhibition is due to take place in 2022), its practice is longstanding, approaching two decades of existence as this tumultuous year comes to an end. The initiative to develop ruangrupa in 2000 was led by artist Ade Darmawan, artist/filmmaker Hafiz and writer Ronny Agustinus, among 20 others from Jakarta, Bandung and Yogyakarta who participated in a fundraising exhibition at Cemara 6 Galeri in southern Jakarta. Its founding came about two years after the resignation of Indonesian president Suharto and the end of the New Order Regime (1965–98), during the ensuing Indonesian reformasi period that brought about social, political and cultural change in the nation, including legislation that permitted some decentralisation of the government, and more tolerance for dissent and democratic reform. As art historians such as Thomas Berghuis and David Teh have suggested, this historical moment coincided with a period of increased international attention on contemporary art in Southeast Asia, and experimental art collectives such as Ruang MES 56, established in 2002 by a group of artists in Yogyakarta, R.A.P. (Rumah Air Panas), founded in 1997 in Kuala Lumpur, and Green Papaya, launched in 2000 in Manila, to name a few, were deemed to have played an important part in this development. Both Berghuis and Teh venture that ruangrupa’s work marked a clear break from post-Cold War art produced under the authoritarian practices of censorship of the New Order and exhibited only after obtaining permits from the Department of Culture and Department of Home Affairs, the military and the police. Instead, ruangrupa’s projects operate using new modes of free circulation and currency within its national borders and internationally, an approach seen as epitomising the ‘contemporary’ in art practices across the Southeast Asian region.

While its members have developed individual creative portfolios across different disciplines, ruangrupa’s collective practice is driven by the lack of infrastructure support and opportunities for contemporary art discourse and practice in Jakarta and Indonesia, the pragmatic need to share resources of space and equipment, and the urge to democratise artistic and social participation by engaging with broad communities, as well as students and young artists. The results include workshops, zines, festivals and exhibitions. It was during these intense and expansive community projects that ruangrupa began to develop their practice of lumbung, a working model based on the communal surplus-grain warehouse intended for shared future use. In 2003 ruangrupa founded one of the major bi-annual events in Jakarta, OK. Video – Jakarta International Video Art Festival (now called Indonesia Media Art Festival), an ongoing thematic festival that presents local and international video and new-media art in various public locations across the city. One of its founding members, farid rakun, recalled that the 2007 iteration of the festival, titled Militia, intended to make a tour of more than 30 Indonesian cities in the space of a year or so, an endeavour that demanded such effort that it nearly broke up ruangrupa. But the experience brought it invaluable knowledge of the different operations of collectives in Indonesia. Furthermore, in June 2010, Darmawan and Rifky Effendi co-curated Fixer, a survey showcase of 21 artist collectives and alternative spaces from across Indonesia at the Jakartabased North Art Space. While the exhibition lasted only ten days, it was another important milestone for Darmawan, and arguably, other members of ruangrupa, for gaining insight into different models of collectivising as well as forming strong relational networks with collectives across Indonesia – which felt like a political gesture in view of the previous autocratic regime’s intolerance for civilian organising.

By 2017 ruangrupa’s networks and insights into how to collectivise across different contexts and sites led them to activate inclusive collaborative projects such as the RURU Radio project, an online streaming radio with artists and interdisciplinary creatives that discussed everyday issues faced by people in the city of Jakarta. Ruangrupa also began to assert its influence via its work with the Jakarta Biennale, which rakun describes as a process of hacking the resources of the institution in transforming arts infrastructure and developing artistic agendas. Founded in 1968 by the Dewan Kesenian Jakarta (Jakarta Arts Council) as Pameran Besar Seni Lukis Indonesia (Grand Exhibition of Indonesian Painting), before its name change in 1975, the Jakarta Biennale had been suspended after the fall of the New Order in 1998. In 2009 ruangrupa was appointed artistic director of its revival edition, then ruangrupa members (such as Darmawan, rakun and Hafiz) individually undertook various executive and interim directorial duties for the 2013 and 2015 editions, until 2017, when the Jakarta Biennale worked with Melati Suryodarmo to further develop and establish the significance of performance art in Indonesia. Most recently, its work of resource-building and -sharing returned to its homebase with Gudskul, established as a ‘collective of collectives’ with Serrum (founded in 2006) and the printmaking collective Grafis Huru Hara (founded in 2012). Gudskul not only learned how to share land, assets and equipment, but also built transparency and mutuality into its financial operations.

The shift, then, is that ruangrupa is no longer interested in merely showcasing collectivising and activism, as it had via survey projects like Fixer, recognising that the artworld can be quick to appropriate cultural capital – as manifested in the inclusion of many socially engaged and issues-driven projects in largescale exhibitions. Ruangrupa’s intentions run deeper: to harness exhibitions such as Documenta, together with its budget and network, as a lumbung of shared resources to activate transformations in art practices and the material economies of hyperlocalised art organisations, with the longer-term vision of building and activating sustainable global networks for the redistribution of power. How this manifests remains in process.

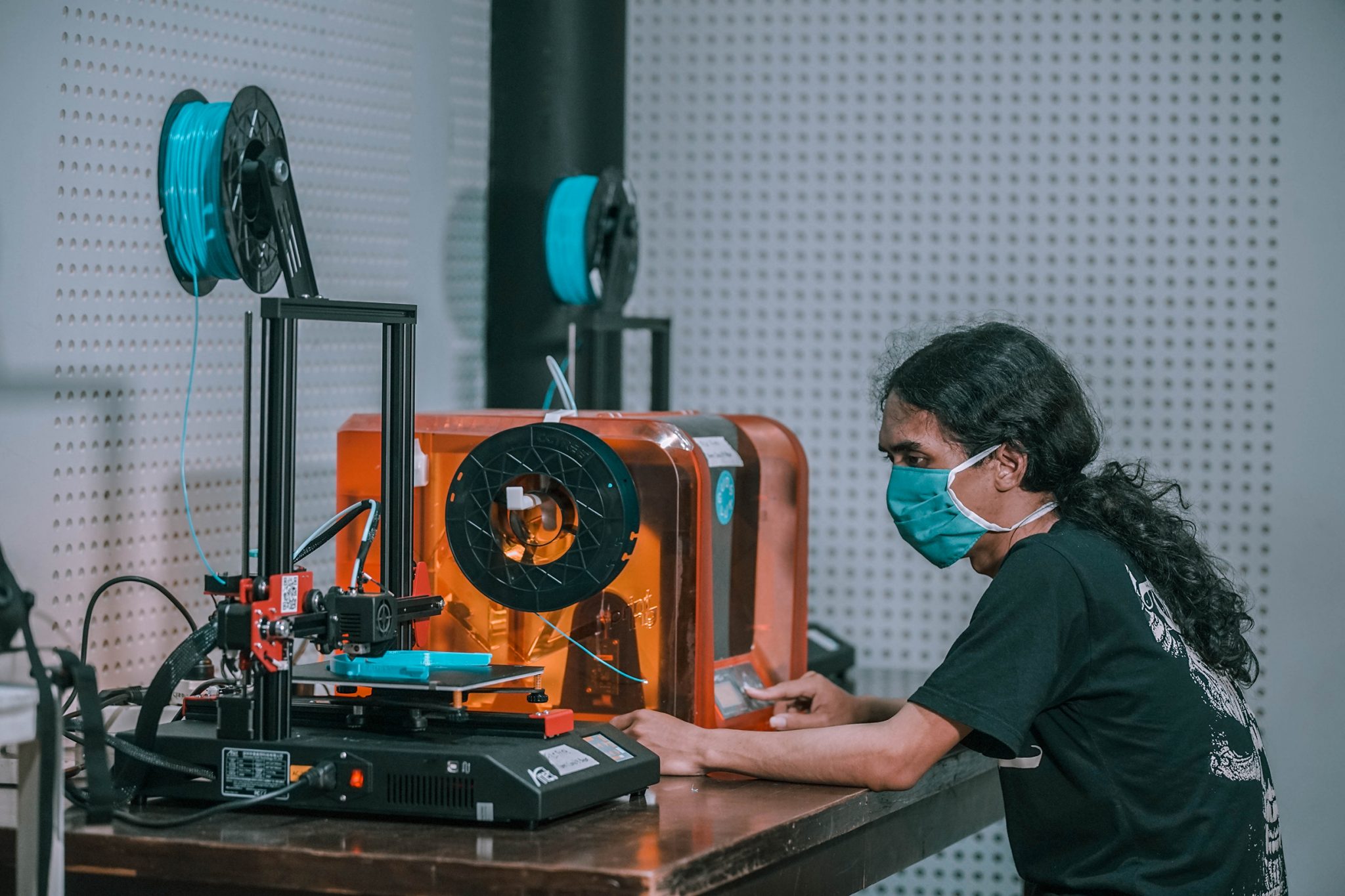

I ask how ruangrupa’s ambitions have been affected by current global conditions, including worldwide travel restrictions, the loss of jobs and small businesses, the disruption of life and increased political upheaval. In relation to their operations, rakun describes it as “winter comes early… we thought we would have time to prepare for the crisis, but the crisis came early… we feel the need to accelerate the process, instead of postponing it”. While the practical implementation of schedules, travel plans and meetings has been disrupted, and currently the ruangrupa curatorial team is split between Kassel, Makassar and Jakarta, rakun is convinced ruangrupa’s documenta curatorial concept of “lumbung needs to be practised as soon as possible” – both by itself and by its artistic lumbung partners. However, rakun continues, the unfolding of this curatorial vision has to be reconfigured – instead of perceiving the process leading up to the 2022 exhibition as the primary occasion to present art and engage the public, the narrative has now been flipped – ruangrupa is considering how documenta may activate itself and its participants now, in our current time. Its take on how this reframes ‘contemporary art’ to fit the times is pragmatic, says rakun: “Forget about art for a minute, for an hour, for a blimp of time, because then maybe you can see the world in a much more useful and fruitful way, much more hopeful. I think we don’t need to fight for the supremacy of art in that sense… the insecurity of that question to begin with… the existential insecurity of art.” What this means in practical terms is that Gudskul, for example, has temporarily put aside its art education programme and leapt into the fray to respond to frontline needs in Indonesia, by transforming its space into a production workshop for healthcare and medical apparatus utilising its 3D printers and other materials, and using its artistic networks as a distribution chain to ensure the kits reach the health workers and hospitals that need them most. Instead of art, the RURU Shop onsite sold pesticide-free vegetables when local food supplies were impacted.

Like other projects of institutional critique, ruangrupa challenges the idea of institutions as being ‘neutral’, often carrying the weight of national and ideological banners, and aims to work as a double agent: a team of artistic directors for a major exhibition pursuing an activist agenda. In terms of the global lumbung it is trying to build via documenta, ruangrupa has already begun dispersing the exhibition’s decision-making process to the collaborative lumbung partners, such as the Festival sur le Niger in Mali, and Lara Khaldi (as part of the artistic team for documenta fifteen) and Yazan Khalili (as part of Sakakini Cultural Center) working in Jerusalem and Palestine. This serves to provide intense local understanding of working contexts as well as tap into the project budget to sustain local operational costs during the current global turbulence. In harnessing the opportunity, ruangrupa recognises this process is also one of ‘becoming’ – moving from what critics deemed ‘contemporary’ in the globalised art market to a practice that must instead be instrumental in ‘futuring’ a more sustainable, equitable and diverse global art industry to come, one that works less on market competition and more on collaboration and the sharing of resources.

Ruangrupa is no longer the kid hacking institutions from the streets. Rakun acknowledges that ruangrupa has become established and is in its own process of ‘institutionalising’ by undertaking a role such as artistic director of documenta fifteen. It holds power that it intends to wield to construct a new system that allows for other ways of thinking and practice to be sustained. In this, perhaps, the pandemic has levelled a common starting point of reckoning – institutions and players alike now acknowledge that things have to change; they now have to figure out how.