Leela Keshav is the inaugural writer-in-residence of Hauser & Wirth and ArtReview’s ‘Write Now’ programme, which provides time and space for early career writers to develop their craft and ambitions. Keshav was based at Hauser & Wirth’s Bruton location in Somerset, UK, where she created a new series of texts that engage with both her natural and cultural surroundings, and the intersections of the human and non-human worlds, while also connecting with more global discourses about anthropocentrism, the ways in which we measure and record time, among others.

A. Thornback, Holzer, Carson & Sappho: A Semi-Fictitious Account

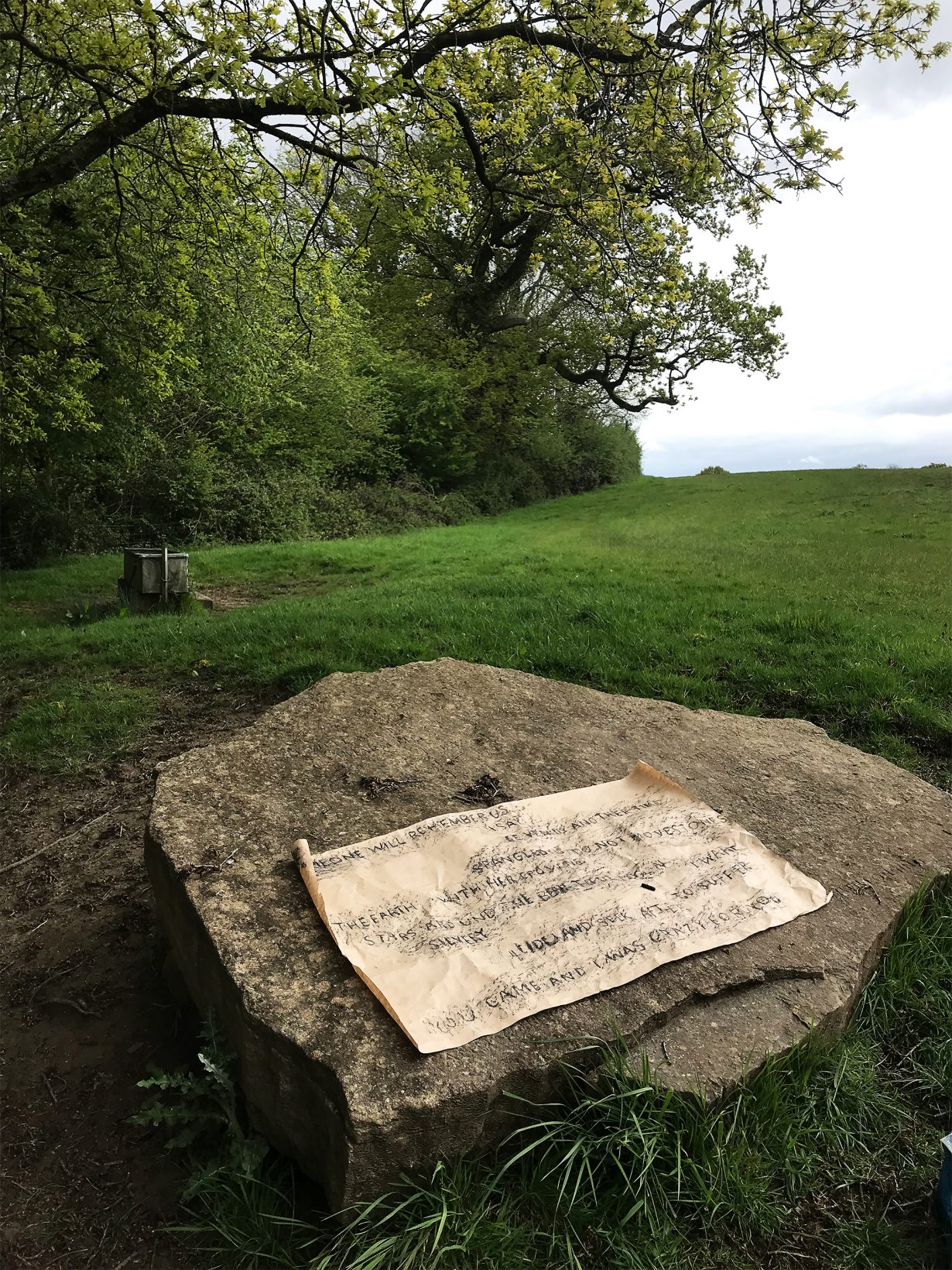

Purbeck Thornback stews in sediment for millennia before meeting Jenny Holzer for the first time. Thornback has never heard of Holzer, though she is already a prominent artist, and – refreshingly – isn’t fazed by her reputation. Holzer has known about Thornback for some time and is desperate to meet them. She approaches the quarry several times before the stonemasons agree to arrange an introduction.

What size? They ask her.

Jagged, she replies.

What shape?

No longer than five-eighths the length of my body.

Thornback, hibernating under a mossy blanket, contemplates their journey from the equator a few hundred million years ago. They’re still exhausted from that trip. Holzer calls down to them. She is convincing.

Not that we have much of a choice, Thornback grumbles.

The cut is quick and nearly painless.

Jagged! Holzer insists, and the stonemasons strike Thornback with repeated blows.

Thornback is acclimatising to their new form. Fresh-cut edges give them a sense of Self they had never experienced as conglomerated sediment. Before, there was only Thornback. Now, there is Thornback and not-Thornback. Not-Thornback is busy and quick-moving and disorienting.

Hands and ants dance over Thornback. They have never been caressed before, and they have to admit it’s not an unpleasant sensation. When the drill strikes, it’s a tickle. Thornback lets slip their first giggle.

Holzer stands near the masons as they chisel into Thornback. Looking at her with one eye, the mason says,

It’s our stone and Carson’s words. What makes it your art?

Holzer smiles.

I’m the conductor, she says.

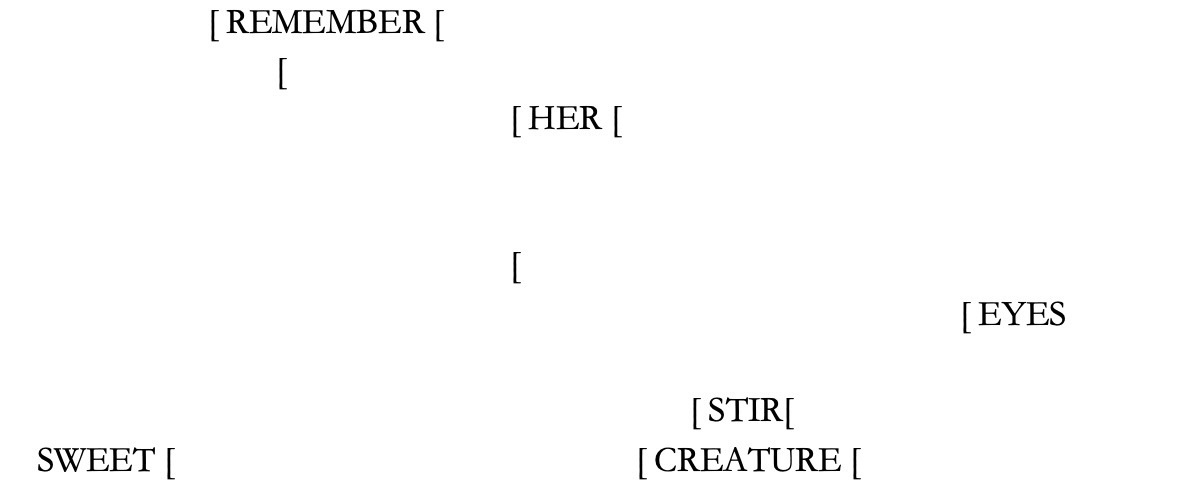

Well after Thornback’s equatorial voyage, but long before Holzer’s first linguistic projections, a poet sat plucking a lyre. She sang words that were eventually transcribed onto papyrus. Some 2,000 years later, two British scholars, Edgar Lobel and Denys Page, translated the Ancient Greek script into English; two decades later classical philologist Eva-Maria Voigt followed suit, translating the Ancient Greek into German. In 2002 Canadian poet Anne Carson compiled her own compendium of Sappho’s fragments, based on Voigt’s work and holding both the original Greek and English translations. The words that first left Sappho’s tongue, transported over millennia, left Carson’s typing fingers as

Thirteen years later, leafing through her copy of Carson’s If Not, Winter, Jenny Holzer gathered fragments to inscribe onto Thornback.

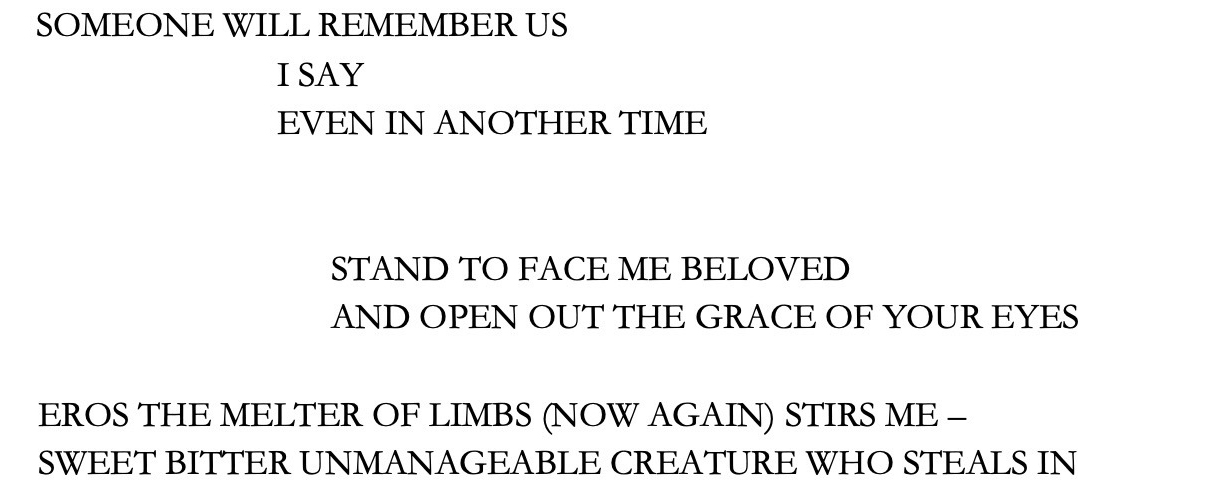

To those versed in English script, the first rock reads

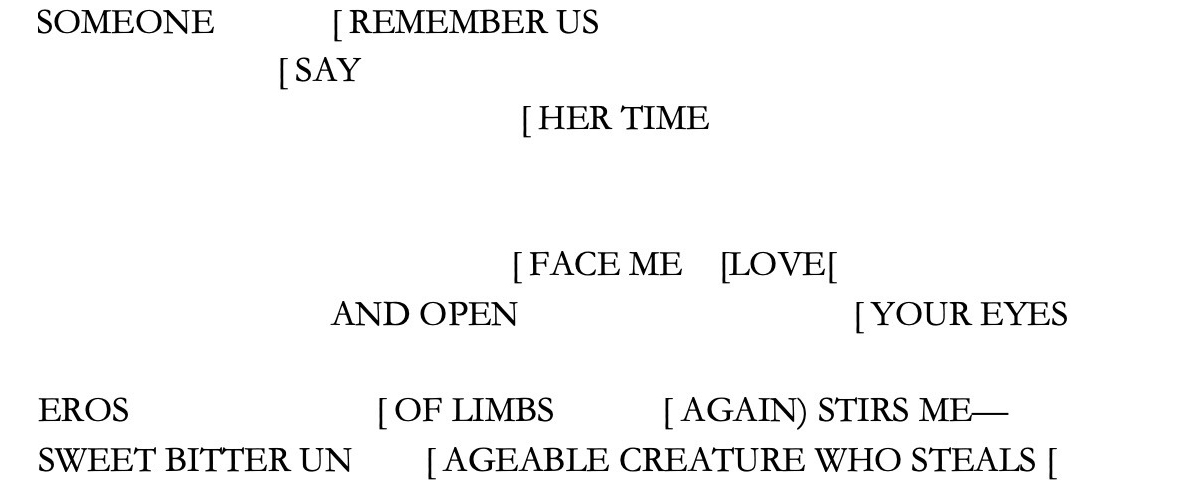

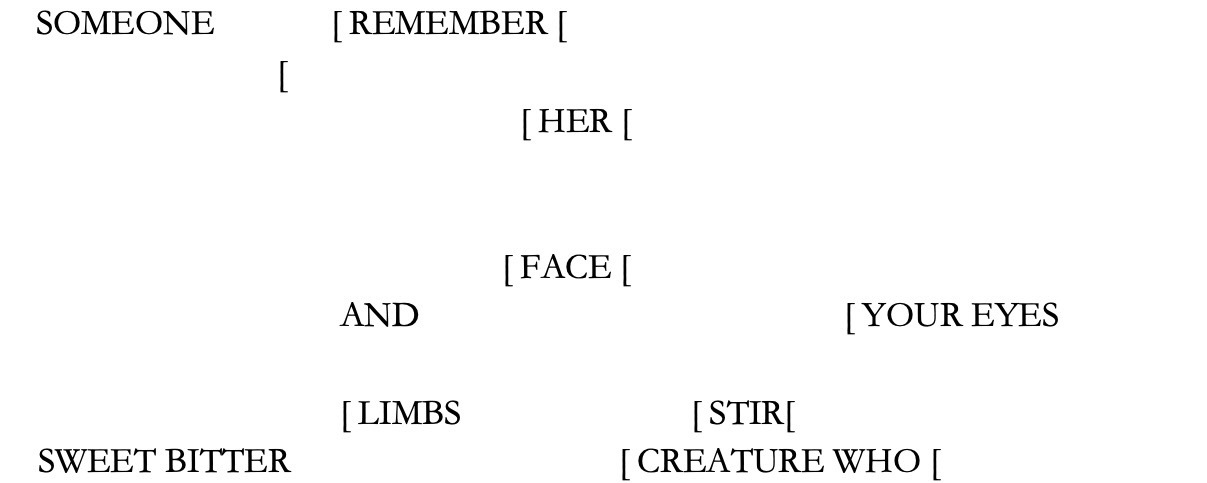

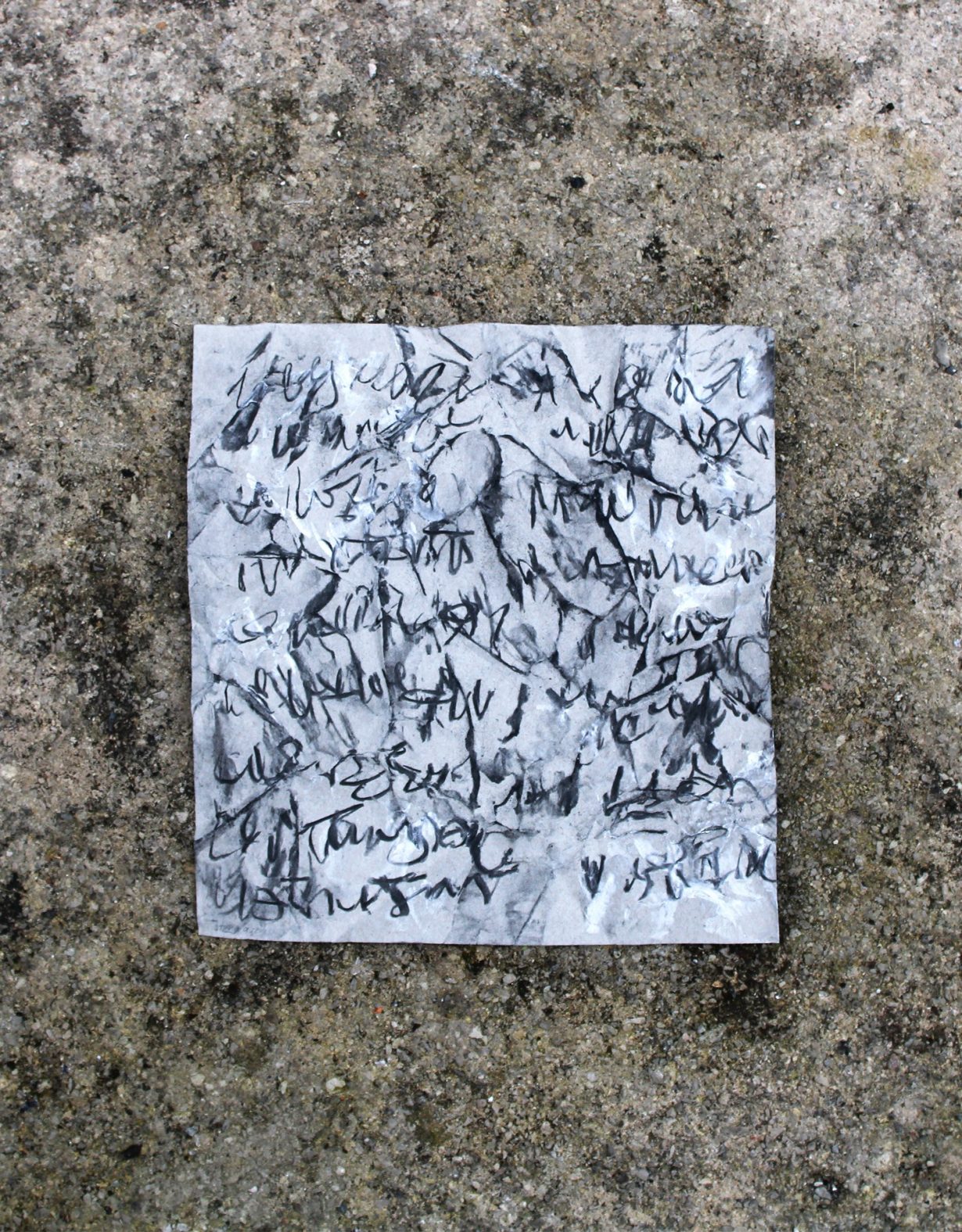

We navigate through translations. Sappho translated music into poetry; unknown hands translated her spoken words into written text; Voigt translated Ancient Greek script into German; Carson translated the German into English; Holzer translated Carson’s lines into fragments; stonemasons translated Holzer’s fragments into Thornback; Thornback translated the word-marks into a gradual process of erosion. What, then, do Holzer’s rocks carry from Sappho’s original lyric melodies? Does it matter? Translation is an artform in itself, inherently interpretive.

Carson indicates destroyed papyrus with a bracket, [; Thornback engulfs [, muddying the poet’s semantic clarifications with their own rocky interpretations. The previous fragments appropriate Carson’s bracketing method to imagine Thornback’s unrelenting absorption of words. Sitting in the Somerset landscape, Thornback’s own bumpy script meets English letters as they gradually lose meaning – or form new ones.

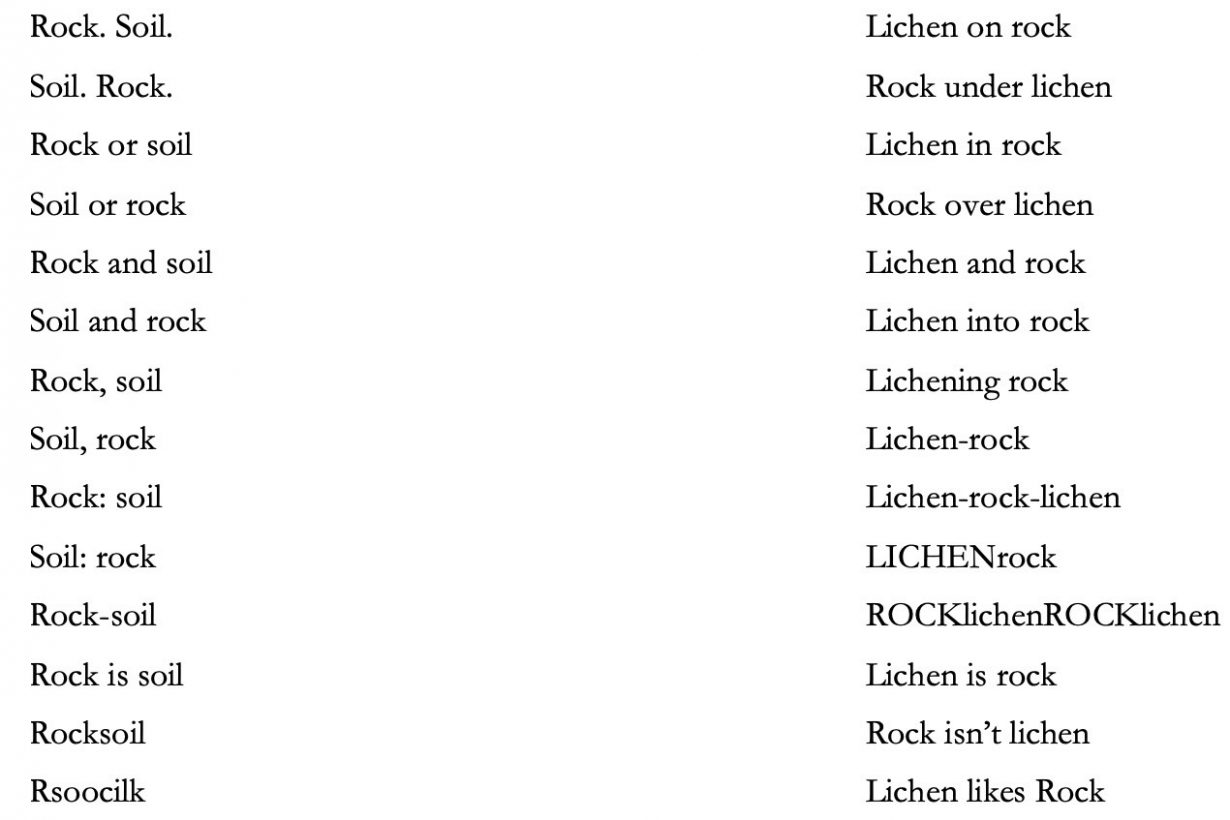

B. An Experiment in Nonduality

C.

D.

Leela Keshav is a spatial practitioner and writer from Canada who has recently completed graduate studies at the Architectural Association in London. Her current research explores legacies of colonial botany, reparations discourse, and conservation beyond the human-nature dichotomy. She is a recent alumna of New Architecture Writers and an editor for AArchitecture. Her writing has been published in the Architectural Review, ROOM Magazine, Unootha Magazine, and Chutney Magazine.