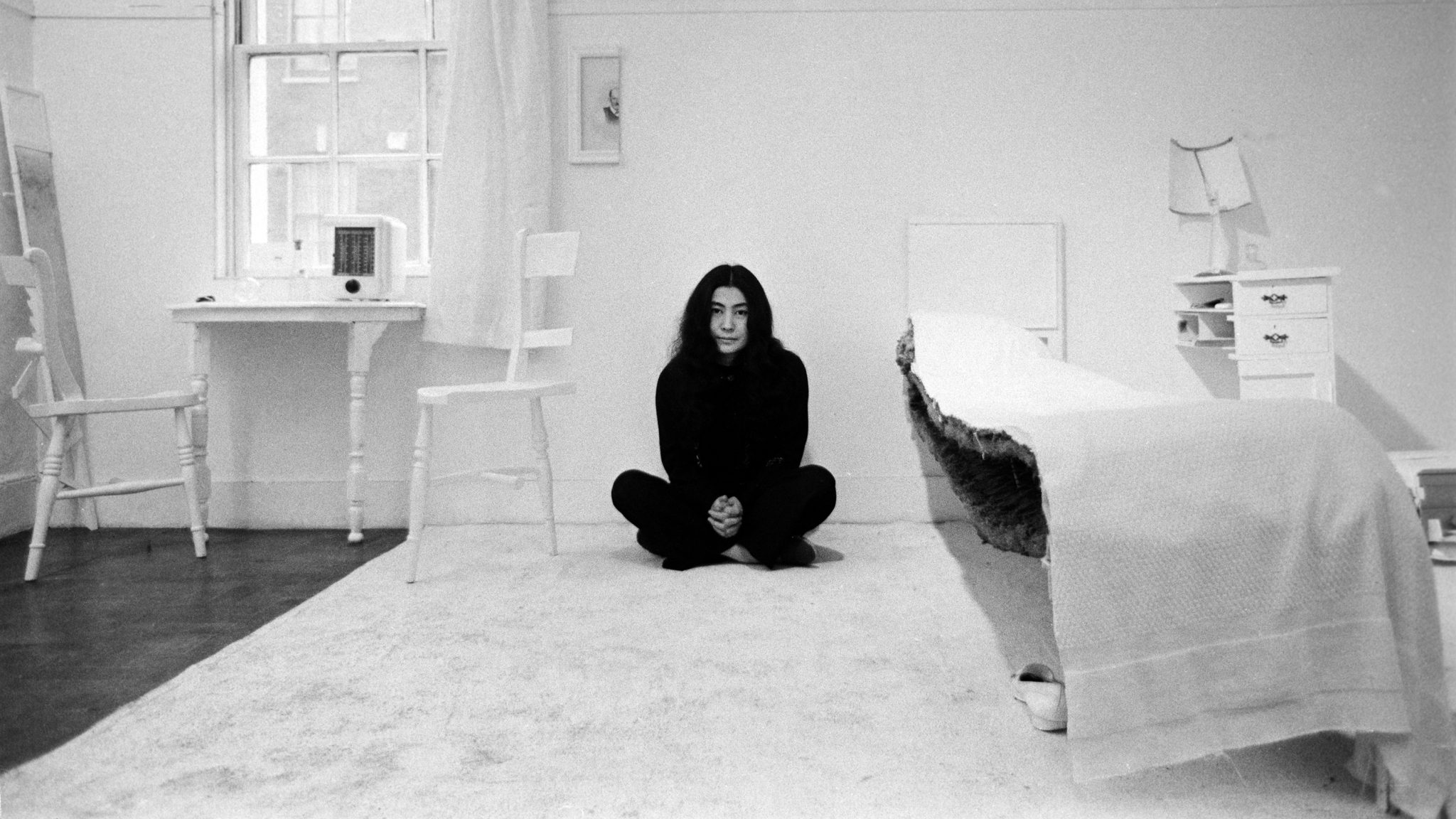

No longer the butt of an old joke, Ono’s works on show at Tate Modern can be seen for what they’ve always been: an intrusion of artificiality and performance into everyday reality

Of course, the big thing about Yoko Ono is that she broke up The Be– just kidding, obviously, given that it is no longer 1972, and I am neither a misogynist nor a moron. That Tate Modern are finally mounting an extensive retrospective of her work, entitled Music of the Mind, is proof that as a culture we have finally begun to look at her and see an artist and musician, rather than a wife, a gag about a plum floating in a man’s hat full of perfume, or the pretentious and castrating bitch who ruined our dad’s favourite band. I cannot imagine how frustrating it would be to spend one’s life producing streamlined artworks that can be summarised in (or simply are) one crisp, poetic line, and then end up so ironically being boiled down to a single punchline in the press oneself, but if I were in her shoes, I fear I might have found myself behaving rather less like a beatific peacenik, and rather more like a brat. Truthfully, the extreme earnestness present in a great deal of her work is at odds with my own pessimistic, dour temperament and, as such, I would not characterise myself as a die-hard fan. Still, I will defend to the death Ono’s right to be taken seriously as a practitioner, and if she has been the butt of many tired jokes about conceptual art over the years – there are, if you can believe it, currently 104 films under the ‘reference to Yoko Ono’ tag on IMDB, and it is safe to assume that most of these mentions are not tributes – it is also the case that most people would not know enough about conceptual art to make those jokes without her having become famous in the first place.

One of the actual big things about Yoko Ono, it turns out, is that she is rather funny, after a surrealist fashion. Viewing Music of the Mind a little before it opened, I had the unusual experience of seeing some final work still being done on the show: as I stood reading a wall text about her collaborations with John Cage, I heard a sudden rush of industrial growling, intercut with beeps and whirrs, and for a moment I believed that I was catching some hitherto unknown Ono-Cage collaboration being piped into the space, before realising that the noise was a tiny cherry-picker entering the room to paint the ceiling. This moment – weird, a little goofily theatrical, and kind of embarrassing – struck me as the perfect Ono-esque occurrence: “By actively inserting a useless act… into everyday life,” she is quoted in an exhibition wall text as having said, “perhaps I can delay culture.” Nothing has made better sense for me of Ono’s work – in particular the instructional texts that were compiled in her 1964 book Grapefruit – than this statement, which explains what she is trying to do mechanically as well as on a conceptual level. A perfect example is ‘Painting to Shake Hands’, which began its life in 1961 as one of those text-based instruction works, and which has the humorous subtitle ‘painting for cowards’. ‘Drill a hole in a canvas,’ it reads in its entirety, ‘and put your hand out from behind. Receive your guests in that position. Shake hands.’ A visual realisation of the piece is also present in Music of the Mind, and it feels like a literalisation of the very ‘insertion’ she describes – a punching through, an intrusion of artificiality and performance into everyday reality.

All this is absurd, but Ono knows it is absurd, and what she wants more than anything else is to trip you up: to stop time for a moment; and to reflect the contradictory states of actual life, which itself presents us with a fairly equal number of moments of great clarity, and moments of great shame. In general, I have always thought that Ono’s best works are those in which she is least political, and in which her ideas remain largely opaque and abstracted. In 2012, as a younger critic who had not long left the irony-drenched 2010s, I remember writing a review of her show at the Serpentine that was suspicious about the straightforward niceness – what I saw as the inarguable nature, I suppose – of much of the messaging in her later output, which favoured peace, and smiles, and the general interconnectedness of all things. I was cynical, and arch, and more interested in provoking laughter than debate. (I also remember, not entirely unrelatedly, being amused by a brief passage in Adrian Searle’s corresponding review for the Guardian: ‘In one room a couple of tables have been set up and you are asked: “Where do you go from here?” You can fold up your response and slip it into a glass. “To the pub,” I thought to reply.”’) On the face of it, an arrangement like 2001’s Helmets (Pieces of Sky), in which upturned soldiers’ helmets are filled to the brim with pieces from a jigsaw of the sky, with the jigsaw representing freedom, is a little pat; funnier and freakier, and thus more effectively subversive, is her Film No. 4 (1966-67), more commonly known as Bottoms, in which she describes herself as ‘string[ing footage of] bottoms together in place of signatures for petition for peace’.

‘WAR IS OVER! IF YOU WANT IT’, Yoko Ono and John Lennon proclaimed in a 1969 advertisement over two pages in the New York Times, and on billboards in New York, London, Paris, and a number of other cities. An image of one of those billboards appears at Tate Modern, alongside a video of one of the couple’s Bed-In demonstrations against the 1955-1975 war in Vietnam. In that clip, there is a shot of Lennon scribbling ‘REMEMBER LOVE’ on cardboard with a Sharpie, and the concentration evident in his posture makes the moment oddly touching in spite of the facile nature of the slogan. The Vietnam war is often referred to as ‘the first televised war’, its duration synchronising with advances in technology in such a way that, quite suddenly, civilians had a screen in their homes that was showing them a stream of death and violence, like a portal into hell. With this in mind, it felt easier to understand the spare simplicity of Ono’s conceptual activism, and as onscreen she and Lennon – motivated by an obvious sense of urgency – pressed their pens into their placards hard enough that the soundtrack briefly dissolved into squeals, I no longer felt the need to be glib about niceness. It would be wonderful if merely wanting peace were enough to make it happen, and perhaps one possible salve for the ache of maintaining that desire in the face of abject helplessness is the kind of gentle optimism Ono employs in her anti-war work. A few days after I saw Music of the Mind, its official opening was interrupted by a peaceful protest calling for an end to the ongoing bombardment of Gaza. Here was another unexpected act being “inserted into everyday life”, and rather than “delaying culture”, it had the effect of poignantly collapsing time: new bombs; a new portal leaking violence into civilian homes; a new request for mercy. “All we are saying,” The Plastic Ono Band plead, in a recording of a 1969 performance that’s included in the show, “is give peace a chance.” There is something unspeakably moving about that modest and qualifying ‘all’, I think. What a small request, and how ludicrous that it was – that it is – necessary for it to be made in the first place.

Philippa Snow is a writer based in Norfolk. Her first book, Which as You Know Means Violence, is out now with Repeater.