From exhibitions hosted on Google Maps to work presented uninvited at Documenta, the Japanese artist imagines a world after hierarchy

On 15 March 2012, one year after the Great East Japan Earthquake caused a major accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power station, Japanese artist Yoshiaki Kaihatsu built a small house in Minamisoma, a coastal city about 20km from the nuclear reactors, siting it 400m outside the official evacuation zone, which by then was known as the exclusion zone. Kaihatsu sent invitations to about 750 members of the Japanese parliament, including the prime minister, to visit the four-tatami-mat house, with its single window facing in the direction of the reactor, to experience the desolation of the evacuated local villages. None showed up. He titled this work The House of Politicians (2012–). Thirteen years later, battered by the elements and restored a few times, the house is continuing to host sporadic activities by artists, activists and residents, even though post-Fukushima antinuclear sentiment among the Japanese public has faded with time. In fact in 2022 the government announced a new plan to extend the lifespan of existing nuclear reactors and build new ones. But The House of Politicians, looking out at the uninhabited landscape, and beyond that the damaged reactors with 880 tons of melted radioactive nuclear fuel (projected to take an unspecified number of decades to clean up), is a stark reminder that the consequences of the Fukushima disaster have not yet played out, despite politicians choosing to paper over that.

Working since the 1990s in a variety of media including drawing, photography, installation and performance, Kaihatsu often directly intervenes in social issues and engages with local communities. His work is usually relational, frequently taking the form of events that rely on the interaction and participation of other people. One of his best-known works is a travelling art exhibition that also functioned as a fundraiser (Daylily Art Circus, 2011–14), which he put together with other artist friends following the earthquake. It toured the disaster-stricken Tohoku artworks to ‘make people smile’. In 2011 he initiated another project that collected disappearing local dialects and folktales from the coastal region evacuated by the earthquake (Cotoba Library [Library of Words], 2011–). The project is hosted on Google Maps, where viewers can click on various pins along the Gulf Coast region running from Fukushima in the south to Aomori in the north. In each location, different people have been filmed telling local folktales in various temporary shelters, such as gyms and community centres.

39 Art Day (Thank You Art Day) is another notable community-focused work that the artist began in 2001 to mark 9 March as a day to celebrate and promote art (the pronunciation of the numbers ‘three’ and ‘nine’ in Japanese sounds like ‘thank you’). Every year on this day, participating museums and galleries extend opening hours, reduce ticket prices and organise special exhibitions to encourage visitors. From its humble beginnings with 20 galleries taking part in the initiative, the project now involves more than 145 art spaces in Tokyo and Kansai, as well as affiliated galleries in countries such as Canada, Norway, Mexico and the United States.

A major survey of Kaihatsu’s prolific practice opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo this summer. Yoshiaki Kaihatsu: ART IS LIVE – Welcome to One Person Democracy features about 50 works made over 30 years. ‘One Person Democracy’ is a phrase first coined by the late arts administrator Osamu Ikeda, director of the influential BankART1929 in Yokohama City, to describe Kaihatsu’s practice. Osamu wrote: ‘Democracy is not the movement organised by a group of people acting under a single motto but the chain reaction where one person’s specific action causes other people to act.’ Hikari Odaka, a curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, has taken up this social-action theme and expanded it to include more personal and idiosyncratic elements. “One of the most distinctive elements of Kaihatsu’s work is his ability to engage in solitary activities while embracing the presence of others,” she tells me over email. Take his rituals of doodling every morning and evening, or attaching a receipt for a purchase he made that day to date the drawing (Receipt Diary, 1992–): a receipt marks an exchange, no matter how brief, with another person, the private ritual of drawing accompanied by a degree of sociability. “Even large projects involving a wide range of people… often derive from his humble and solitary practice that creates a chain effect on other people’s actions,” Odaka adds. “This approach embodies the essence of democracy, where we always treasure not only the collective (society, community, nation) but also the individual.”

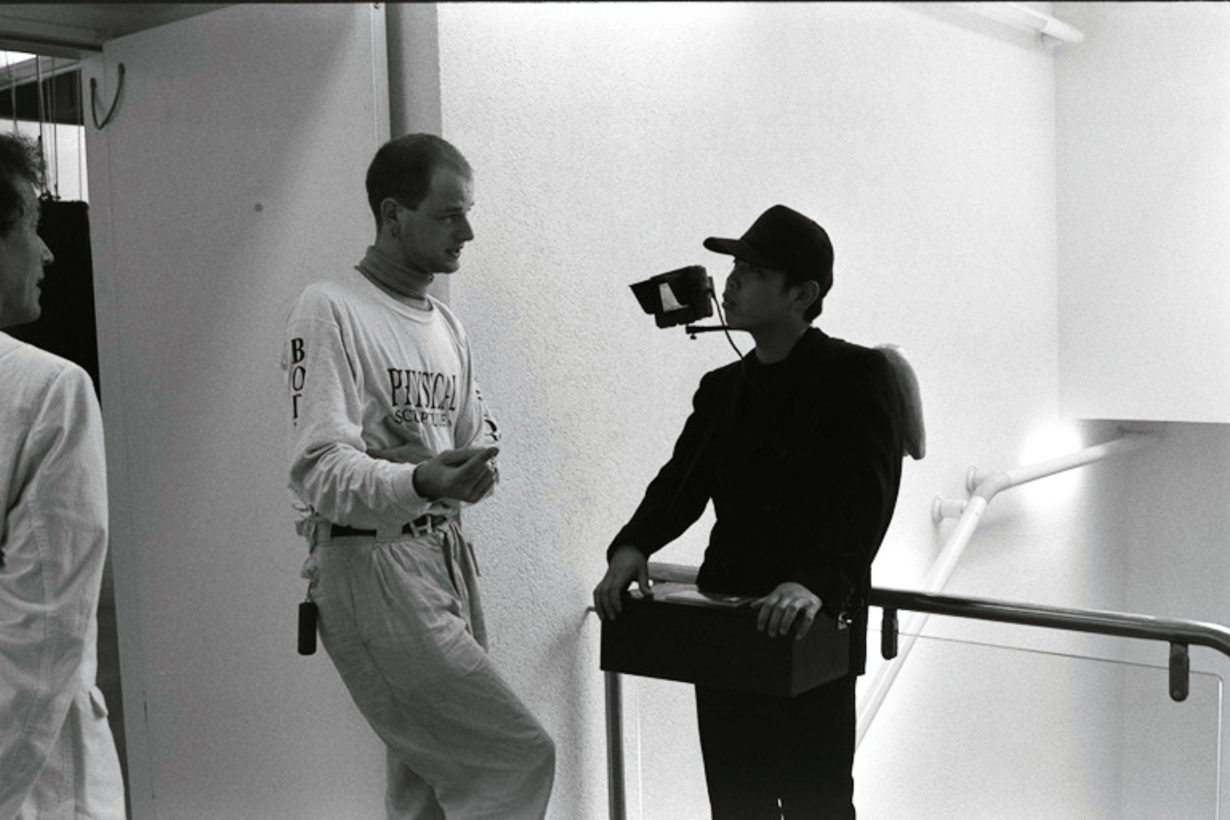

To me, there is another element of democracy that Kaihatsu’s work encourages: an equality of rights and status among people. This may mean disrupting all sorts of proprieties, such as when the artist violated artworld ‘rules’ by showing his own work at Documenta 9 uninvited: he walked into the exhibition hall every day with a small video screen hanging around his neck that displayed a slideshow of photographs of Performance at Documenta 9 (Petit Gallery) (1992). Otherwise, his works simply create a level playing-field by treating everyone in the same way. (A disavowal of status in the context of Japan is likely more significant than in other places, as Japanese society is traditionally more rigidly structured.) For the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale in 2015, he created an underground broadcasting station by digging a hole in the garden of an abandoned school and establishing a radio station. He invited various local characters, ranging from famous actors to retirees, to participate as guests on an informal talkshow, which was streamed live on YouTube (Mole TV, 2014). The interviews were conducted by the artist who dressed in character as a mole, wearing a black furry suit and long white claws, which added to the relaxed and kooky atmosphere, and encouraged a looser, more free-flowing conversation.

As Kaihatsu tells me: “Humans have built a lot of architecture – huge buildings and skyscrapers are the symbols of authority. I wanted to meet people from all walks of life in a place without authority and without hierarchy. That’s why famous people come to this TV station, as well as old men in the neighbourhood. I wanted to create a place where you can talk frankly without hierarchy.”

Born in Yamanashi Prefecture, west of Tokyo, in the landlocked, mountainous Chubu region, Kaihatsu went to art school and originally trained to be a painter. After experiencing a crisis in confidence in relation to his technical abilities, he switched to installation art. Aged eighteen, he encountered the American sculptor Louise Nevelson’s works in a book and was inspired by her monochromatic boxy assemblages made from found wood and other salvaged materials. During his master’s degree studies at Tama Art University, in Tokyo, he started using humble materials in his installations. In 1990 he began handling Styrofoam during his part-time work at a sculpture-casting company, where it was used to make maquettes for bronze sculptures. He consequently turned to making things out of polystyrene foam, and his use of the material evolved into a personal trademark. Some of these creations are sculptural objects, whether a centaur (Centaure 1.5 times, 2004), a space probe (2011: The Year We Make Contact, 2011) or a horse for a Hermès shop window (Barn, 2023). Others are more ambitious architectures, such as a teahouse (Happô-En, a Styrofoam Teahouse, 2001) and a café (Space White Cafe, 2017). Lit from within, these assemblages exude an otherworldly glow with light escaping through the cracks between the Styrofoam pieces. The experience inside is uncanny, too. The oddly shaped blocks used to build the architectural structures often began life as the protective buffer for boxed household appliances; the (negative) shapes of these objects endure within the new builds. Their presence and absence can be felt.

Dust, another form of detritus from daily life, was also a favoured material in his early days. For site-specific works, Kaihatsu likes to sweep up all of the dust from the venue and arrange it to create different effects. In Shadow (1998), he vacuumed the dust from an abandoned house and arranged the particles onto a slanted rectangle on the floor, which resembled a shadow emerging from a cupboard. In Tears Pond (2002), exhibited in New York, he went to Ground Zero to collect dust (the area around the World Trade Center was apparently cleaned each day, but Kaihatsu found a snowdrift, behind which a lot of debris remained). He arranged the dust into a raked circle, a reference to Japanese karesansui gardens, which use raked gravel patterns (samon) to represent the ripples of a pond.

The artist’s work took a more social turn in 1995, when, frustrated with the limited opportunities for exhibiting, he began an ambitious project to mail his sculptural artworks in wooden boxes to places all over Japan. As well as to museums and galleries, he sent his work to the houses of friends or whoever was willing to host (365 Project, 1995–96). The works were sent after the participants signed an agreement to display Kaihatsu’s artwork for a year, during which time he visited and filmed himself speaking with them about art, politics and whatever else came to mind. These interactions were later edited and broadcast on the television channel NHK BS. 365 Project aimed to disrupt the usual methods of exhibition-making and expand the conversation about art from the confines of metropolitan Tokyo to the rest of Japan (“a rebellion against the art industry”, he tells me). But this work also became a turning point that piqued his interest in art’s relevance to society, especially because 1995 was a time of soul-searching for Japan. It was the year of the sarin nerve-agent attack on the Tokyo subway, which killed 13, severely injured 50 and left almost 1,000 others with temporary impairments to their vision, and the Great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake in Kansai, which killed approximately 6,300 people and displaced as many as 310,000 others.

At that time, Kaihatsu felt helpless and didn’t know what he could do. But over a decade later, in 2011, during the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake, he sprang into action with Daylily Art Circus, which connected the victims of the 1995 Kansai earthquake with those of the 2011 earthquake in Tohoku.

He loaded a truck with various artworks, including inflatable ‘air dancers’ in the shapes of giant clowns, animals and flowers, which flapped around and danced like those in front of car shops and petrol stations to beckon customers inside. In the Kansai region, the exhibition also functioned as a fundraiser, with many people affected by the 1995 earthquake expressing solidarity by writing messages of hope and encouragement, donating cash and other supplies. Kaihatsu then took the exhibits and donations to the Tohoku and Fukushima region, stopping at gyms where people were sheltering, as well as community centres and parks, with the straightforward mission of spreading good cheer and distributing supplies.

Kaihatsu said the idea came to him out of “a genuine desire to help people in the affected areas in whatever way I could as a human being. I didn’t know if the people who had lost their homes and jobs needed art, but my job was art”. One of the most touching experiences during this time, he says, was a remark by a mother in the Tohoku region who attended one of his exhibitions. Her family, which included small children, had been affected by the earthquake. Lacking internet access, they saw a notice for Daylily Art Circus at the library and the mother subsequently took them to the exhibition. The mother then told Kaihatsu that ‘[she] felt the children needed this’. Kaihatsu tells me: “It was an experience that made me realise that our activities, which we always thought were not needed by many people, were needed by someone.”

In Japanese contemporary art, the 2011 earthquake is often cited as a critical turning point that brought more social urgency to the sector. There was a turn towards more socially engaged and politically critical art, with more artists working in or near the regions affected by the disaster, creating experiences that combined art, advocacy and disaster relief. Daylily Art Circus, rightly, is often cited as an influential work, bringing food and money to the needy and providing a bridge between different communities linked by their common experience of disaster, death and displacement.

As many of Kaihatsu’s works are temporary social interventions, they are shown in the form of documentation in his exhibition. Balancing out the historical material are many interactive works that explore various aspects of freedom, with recent works encouraging people to speak up and be heard. This could take the form of responding to various statements by pasting stickers (blue for ‘yes’, red for ‘no’) on a wall (Vote YES/NO in MOT, 2024). Such statements include: ‘I don’t think we should accept immigrants’, ‘I don’t think vaccines are necessary’. Those in a more oratorial mood can stand at a lectern covered with faux fur to deliver a speech of up to 90 seconds ‘about anything: about your pet, about art, about your hobby’ (Speakers’ Corner in MOT, 2024). Then there is the space for you to demonstrate political solidarity with Ukraine in Welcome to Everyday Demonstration (2024–). Since the Russian invasion began in 2022, Kaihatsu has collected images of placards from pro-Ukraine demonstrations around the world and posted them on social networks. In the museum, these images have been made into stickers, and visitors can place them onto a big wall to make a gigantic collage mural. Interestingly, the pro-Ukraine stance aligns with Japanese foreign policy. The notoriously immigration-resistant Japan has so far accepted 2,500 Ukrainian refugees. According to figures released by the Kiel Institute for the World Economy in June, Japan is in sixth place in terms of countries who have provided Ukraine with financial aid (more than €7 billion has been allocated by the country so far).

The exhibition will also be a place for conversation, exchange and fun. A new iteration of Kaihatsu’s popular 100 Teachers project will be included. This is a programme that he has held in various places in Japan over the past ten years. During the show’s run, 100 teachers who are experts in various fields are invited to give 40-minute lessons to the general public. August’s programme includes lessons by Gloomy Teacher, a self-identified pessimist who wants to encourage a more neutral understanding of ‘darkness’ in the human psyche; Heavy Rain Teacher is a river expert and meteorologist covering questions such as ‘why does it rain?’, ‘are there different types of rain?’ and ‘where does rain go?’ Other teachers include: Turning-all-Kaihatsu’s-works-into-Dance teacher, Nininbaori teacher (Nininbaori is a Japanese comedic act where two people wear the same large coat and pretend to be one hunchbacked person) and Yonaguni Teacher (Yonaguni is the western-most inhabited island of Japan). The programme’s motto is: ‘Everyone a teacher, everyone a student’. Indeed, by tapping into our collective knowledge and experience, 100 Teachers is yet another instance of Kaihatsu’s democratic flattening of a society which is guided by curiosity, humility and humour.

ART IS LIVE – Welcome to One Person Democracy is on show at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (MOT) through 10 November