The artist has for decades shown how children become contaminated by the adult world’s ills, but a new exhibition hushes the anguish they’re suffering

Viewing the first major survey in London of Yoshitomo Nara’s four-decade career, I’m reminded of the archaic expression ‘children should be seen and not heard’. Nara is best known for his paintings of mad-eyed kids who hypnotise us through their pained coalescence of cuteness, or kawaii, and psychic trauma, with the former acting as a salve for the latter while the latter bites back. Careful, I suspect, not to upset the Japanese artist’s saleroom superstardom (or the saleability of his merch), the show’s opening wall-text foregrounds the pleasing qualities. While it starts by suggesting that his subjects are ‘melancholic and uncertain’, they become, ‘over the years, increasingly serene and meditative’, heralding Nara’s ‘enduring support for peace, and his deep interest in sharing ideas about home, community, the natural environment’. Never mind that these maniacal kids – with their rageful, weeping eyes, their bandaged heads and angry slogans – appear far from alright, contaminated as they seem to be by the adult world’s ills.

The first work encountered is the installation My Drawing Room 2008, Bedroom Included (2008), a white house patched out of planks and corrugated boards, too small for an adult to stand in, the floor strewn with drawings. Popular music from the 1960s and 70s – The Beatles, Bob Dylan – blares from inside, corresponding with several of the 350-odd album sleeves covering the gallery wall nearby. On the outside a painted sign reads ‘PLACE LIKE HOME’, in which a girl stands with her eyes closed, as if dreaming of elsewhere – perhaps this rickety cabin of creativity, or the drawings that are made therein. Conjuring a portal between the physical and the imaginary, the installation brings together the unbounded genius of wilful naivety and the upbeat rebellion of prepunk rock. It isn’t as obviously pain-ridden as the rest of Nara’s work, yet there is unease – as well as cuteness – in the bandage on the girl’s head and the pile of angsty faces on the floor.

While the layout eschews any strict chronology, we gradually get a sense of Nara’s trajectory from the diminutive, haphazardly placed wall labels, one of his most important formative moments being his encounter with neo-expressionism at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where he studied from 1988 to 1993. In Give You the Flower (1990), a fish-tailed humanoid offers a yellow flower to someone in a dress, their faces almost kissing, though the former is perspiring wildly and the latter grips a knife. Here Nara crudely collides naivety and violence to mine the neuroses that sweetness often seeks to cover up, laying the foundations for his fantastical child-portraits, which he began during the early 1990s. Broadly, these evolved from tightly delineated, more overtly mangalike characters such as the clench-fisted, bloodshot girl in Missing in Action (1999), into the absorbingly layered and soft-edged, galactic-eyed figures – often on the verge of tears, their faces blown up to fill outsize frames, giving them a totemic presence – in No Means No (2006) and Midnight Tears (2023).

Just as ambiguous are the paintings Nara is said to have made in response to the catastrophic leak at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in 2011. The repurposing of planks and boards as a surface on which he painted Emergency (2013) may partly suggest ‘recovery and repair’. Yet the thrust of the work is its depiction of a weeping girl on a hospital bed spinning out of control – beyond the foot of the frame, the one visible wheel ‘swooshing’ – its sutured, makeshift materiality suggestive of psychic scarring and, indeed, emergency. Although Nara has explained that the disaster deeply affected him, one cannot isolate Fukushima as the only source of his children’s plight. The recycling also recalls Nara’s discovery of neo-expressionism during the 1980s, as well as his signature use of patches of ripped canvas – as seen in his 2001 painting Too Young to Die, which depicts a child smoking a cigarette, the layered stitching metonymic of accumulative wounding.

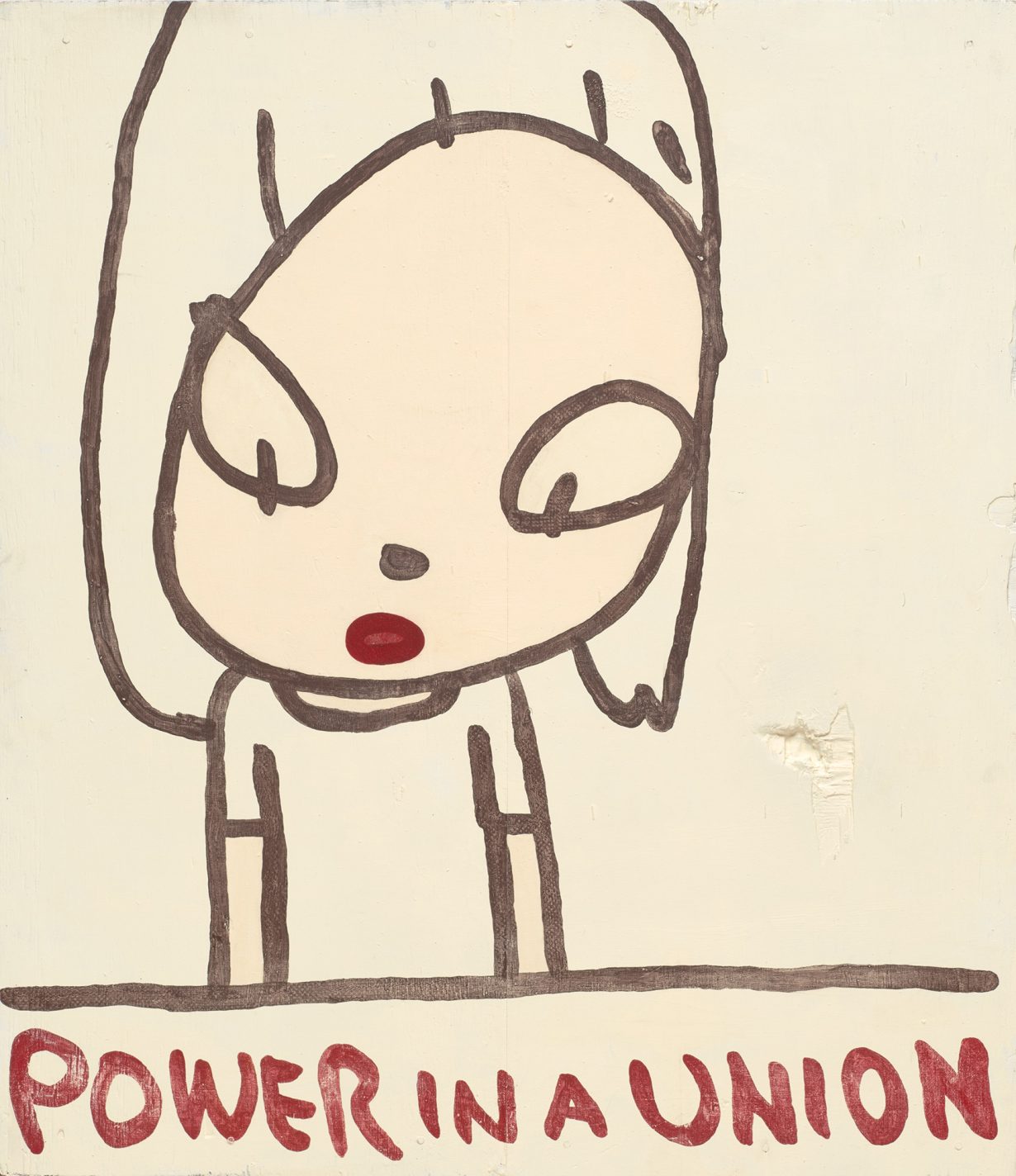

In Dead Flower 2020 Remastered (2020) – Nara’s enlargement of an earlier painting of his from 1994 – a knife-brandishing, serrated-toothed child turns to look back at us, proud to have decapitated a flower. One eye is bright yellow, a reflection of the lightbulb dangling above where the flower used to be or, perhaps, a mutation. The image recalls Nara’s watercolour Missing in Action – Girl Meets Boy (2005), in which one of the child’s eyes bears the imprint of the atomic blast over Hiroshima – a work curiously omitted in this show, which happens to coincide with the 80th anniversary of the nuclear age. Such curatorial pussyfooting makes the placement of From the Bomb Shelter (2017) and Stop the Bombs (2019) – the latter painted on planks with the title emblazoned above the child’s head to resemble a protest placard – at the end of the show, on the bunkerlike ground floor, feel like a tokenistic afterthought. Such manoeuvres seem like an attempt on the part of the gallery (and oddly the artist, who presumably had a say in the matter) to foreground the sweetness of Nara’s subjects while hushing the anguish they’re suffering. While the show risks implementing kawaii’s dissociative tendencies to downplay darker truths, Nara’s work arguably seeks to expose them as well as our predilection for cuteness as a coping mechanism, so it’s fitting that in this final room is I’m sorry (2007). A kid kneels on a box – a ‘naughty’ box, perhaps – with the title written on it, looking up at us in supplication, as if apologising for having spoken out of turn.

Yoshitomo Nara at Hayward Gallery, London, through 31 August

From the September 2025 issue of ArtReview – get your copy.