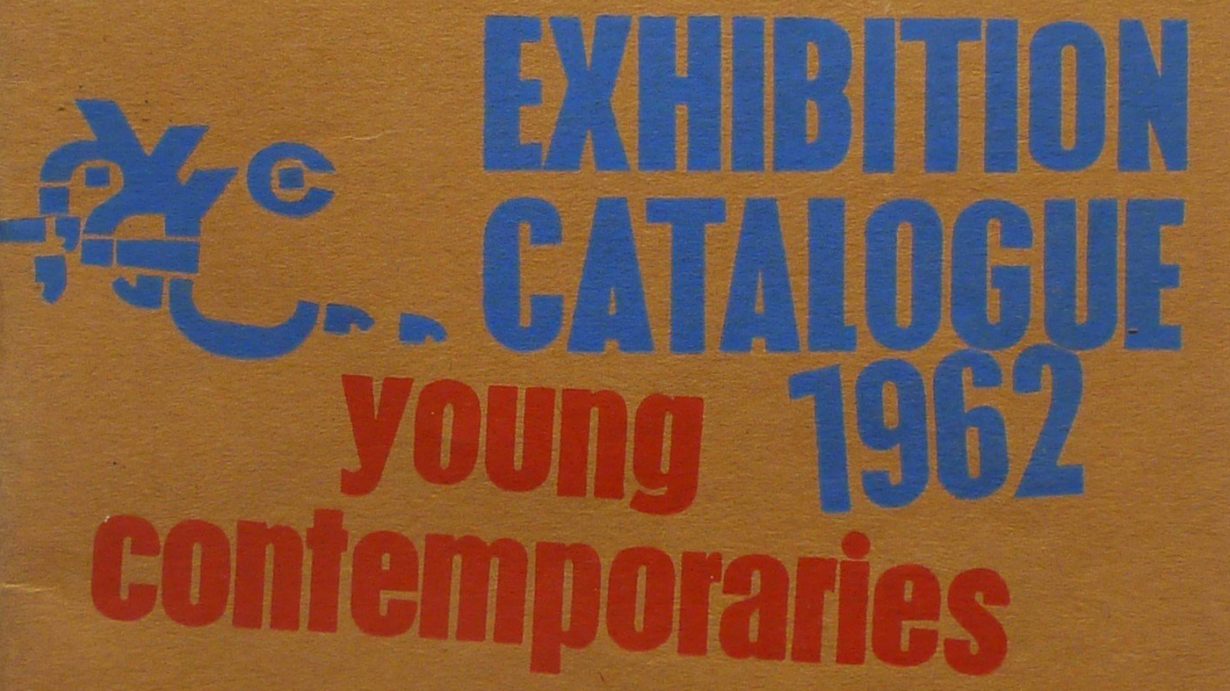

From 1962: Our critic called it ‘by far the most significant Young Contemporaries Exhibition’, featuring Derek Boshier and David Hockney, among others

It was daylight when I went into the exhibition; dusk as I came out. Opposite the end of Suffolk Street, across the Haymarket, a tall rectangular tangle of scaffolding climbed ten stories into the air; cranes and concrete and glass clawed and shouldered their way out of it to assert a new office block overhanging Her Majesty’s Theatre, glowing with photographs and the names of stars. The sky was dark, dark blue: round Piccadilly, still unraped by Cotton and Clore; up Shaftesbury Avenue, along Coventry Street and Leicester Square into Charing Cross Road where hard lights winked on glossy guitars, suede jackets, books, pin tables, everything was gaudy, golden, chromed, gleaming, flashing and revolving neon-hieroglyphs in red and blue and green above the swooping, rumbling spate of cars and buses, signalling to the hurrying thousands already pouring out of shop and office, into theatre, restaurant, and cinema, or the slot-machine oblivion of the Tube.

This is the world – urban, whose factory-made, mass-produced and tele-recorded complexities inform everything on the walls of the R.B.A. Galleries. The Young Contemporaries, this year more than ever, is not an exhibition out of which to pick individual works. I found any attempt to do this worse than useless; it positively hindered the necessary submission to the total effect. Not until we have absorbed the totality shall we begin to sense a pattern of values by which to assess particular achievements.

Am I saying, then, that these young painters and sculptors have abandoned values, and that we must go along with them?

On the contrary; they are very clearly seeking values, and this makes it worth while, even imperative, to go with them; most of the familiar landmarks are feet below the flood; soundings, rather than bearings, are what we need. Most of what is here is undertaken not so much to propound answers as to pose questions, even in the high proportion which is patently programmatic.

In new guises, and wearing new fantastic fragments of our old clothes, the tightrope-walking and symbol-rigging of the ‘twenties and ‘thirties assails from every side – assails the artists no less than the spectators.

For me, the rainbow hanging over this flood lies in the fact that it is fundamentally a flood of imagery, half-resolved because continuously experienced; not recollected in neat tranquillity, but raw, tasteless, and living. Pin-ups and pin-tables, space fiction and city construction, the pabulum of admass and the monitory shapes of motorways, are all pouring furiously through the shifting sieve of consciousness into the patterns of a fully urban art. Behind this visual babel, these youngsters are pressing towards comprehension and communication. Is the language sometimes frightening? It’s a world full of frightful, as well as wonderful, possibilities.

I would put money on Derek Boshier, David Hockney, Ingham, MacLeod, Phillips, Nicholas, Roberts, Barry Ward, Alan Welsford, Agis, Annesly, Jacques Michel, Matt Ruga: Laurence Whitford’s Thunderbird 7? I’m not sure.

Maybe all the actual objects will finish up in the junk-heap: all the same this is by far the most significant Young Contemporaries Exhibition since they started.

This article was first published in The Arts Review Vol XIV, No.3, 1962