Shows to catch in Thailand, Australia, Japan and Vietnam

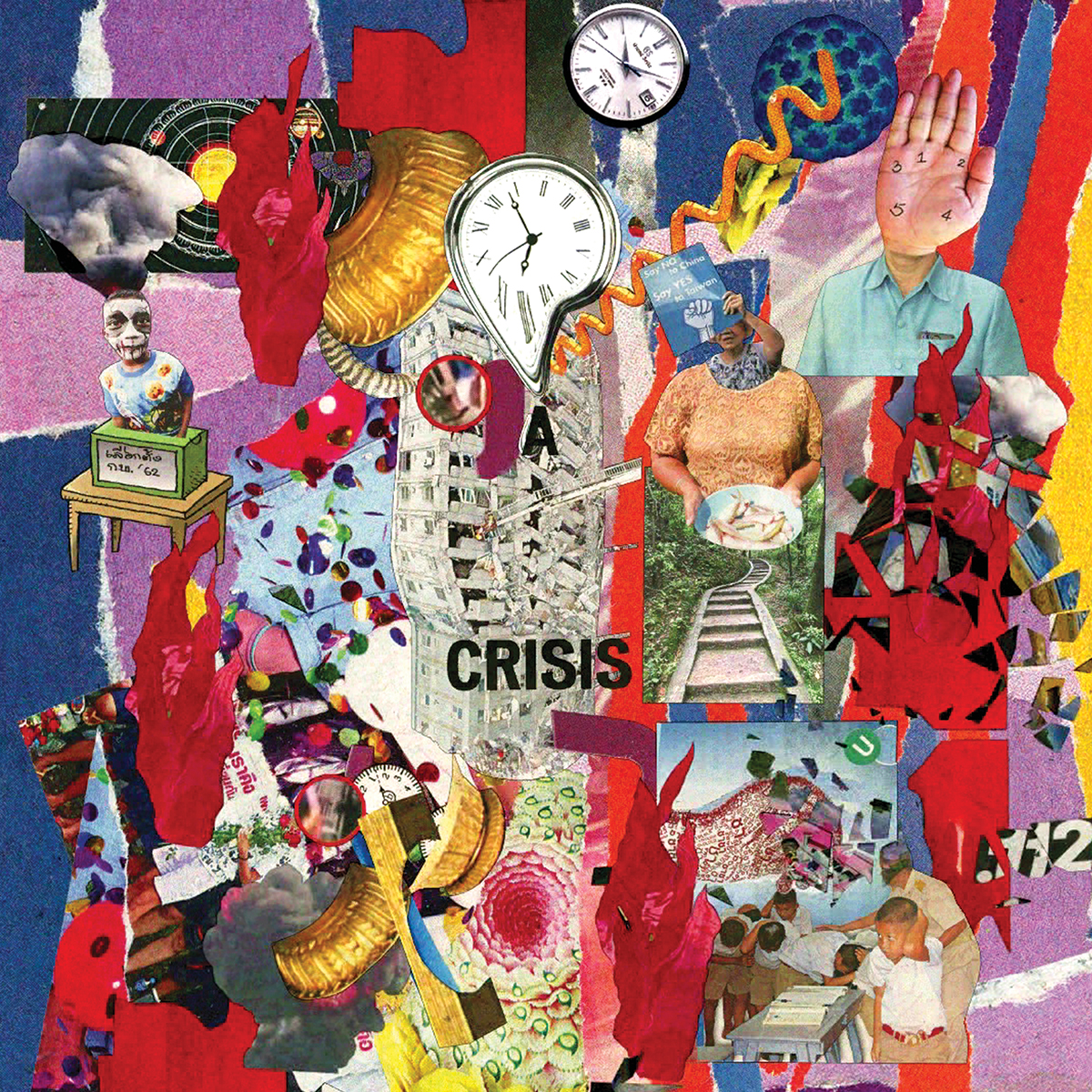

An exhibition of work by locally based filmmaker Chulayarnnon Siriphol marks the postlockdown opening of Bangkok City City Gallery (through 9 August). Siriphol takes aim at some of the happiness illusions that permeate Southeast Asia, but here his target is not the joyous Disneyland-type leisure parks staffed by migrant workers selling audiences a good time and an escape from reality (the audience’s, not the workers’, although it’s the someplace-inbetween wherein lies the rub), but rather the ‘Restoration of Happiness’ PR campaign that followed the 2014 military coup d’état in Thailand. It was at that point that Siriphol started making a series of daily collages that aimed at moving past the doublespeak and confronting realities. Cutting pieces of text from daily newspapers and layering in kaleidoscopic imagery to make the works that are on show here. The exhibition title, Give Us A Little More Time, is drawn from a particularly jingoistic ditty composed by General Prayut Chan-o-cha, former leader of the National Council for Peace and Order, as the military junta styled itself during its five-year reign. While he was asking the nation for ‘a little more time’ to complete the junta’s ‘reforms’, he also claimed that 99 percent of the population was happy with the government’s performance. ‘Crisis’, screams one of Siriphol’s collages, above a series of explosions and cowering schoolchildren. ‘It saddens me’, Prayut said, following pressure to restore civil liberties from overseas, that ‘the United States does not understand the way we work.’ It does now.

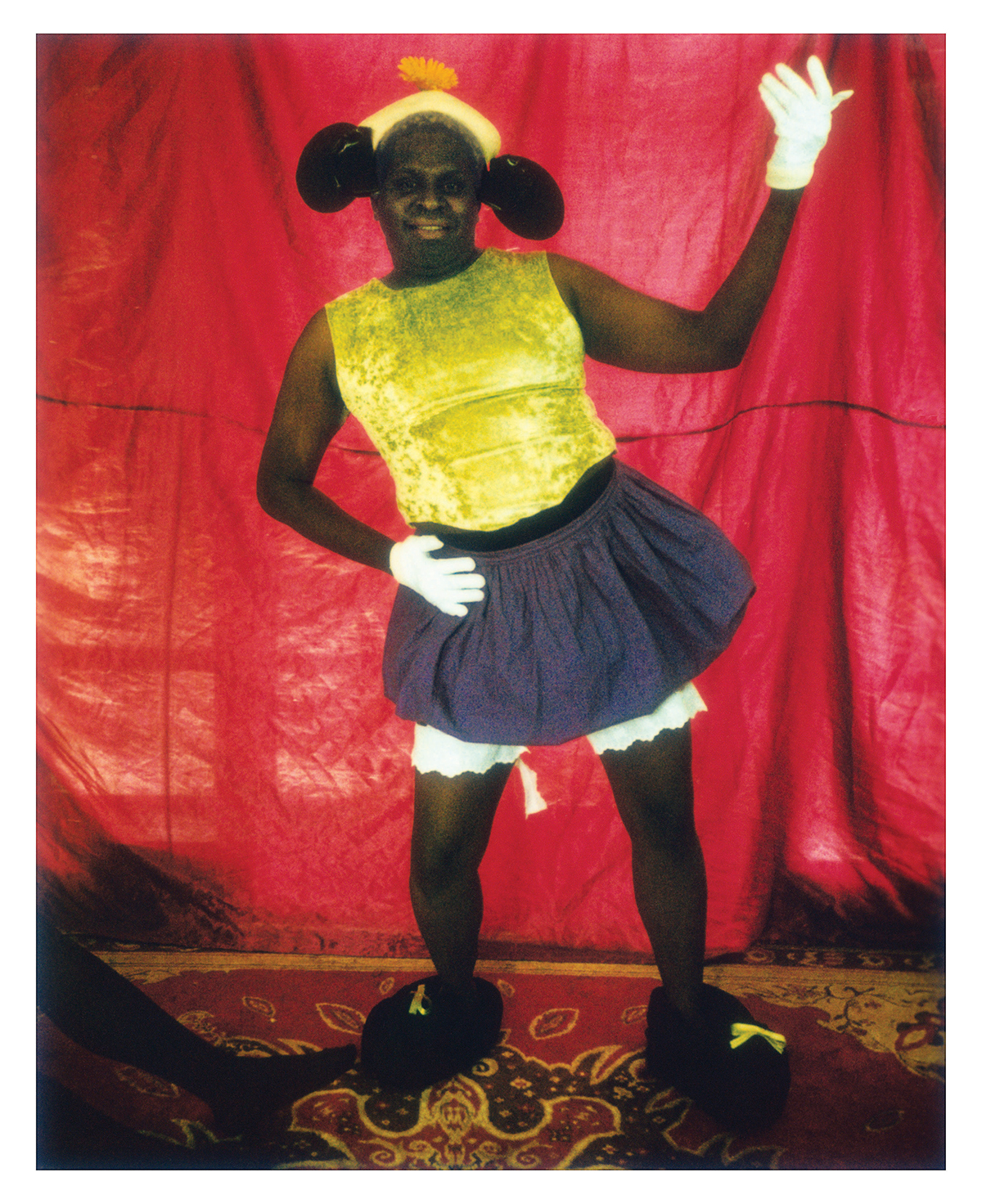

The National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, is hosting Destiny Deacon’s first solo show in over 15 years (through 9 August). Titled Deacon, the retrospective features work in a variety of media, spanning 30 years of the artist and political activist’s production. Deacon is a descendant of the KuKu (Far North Queensland) and Erub/Mer (Torres Strait) people and is known for her photographs of family and friends posing with black dolls and various kitsch items of ‘Aboriginalia’, and for works that feature the dolls alone. The photograph Melancholy (2000), for example, features a headless black baby doll wearing a playsuit stuffed into the skin of a watermelon that serves as a homemade crib, its head perched atop the pink flesh to its side. (Government policy allowed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island children to be forceably removed from their families from the mid 1800s onwards.) Where’s Mickey? (2002) features a Torres Strait Island man (Luke Captain) dressed up as Minnie Mouse and a colour scheme that evokes the Aboriginal flag. It goes without saying that Deacon’s darkly comic work is long overdue this kind of exposure.

Meanwhile, a lack of physical connections has meant that this year’s edition of the Yokohama Triennale (Yokohama Museum of Art & Plot 48, through 11 October), curated by Delhi-based Raqs Media Collective, has had to adapt to our changed circumstances, with the exhibition, titled Afterglow, now being built up during the course of the event’s run and some of its projected commissions becoming reinterpretations of existing works. (For more on the last, see ArtReview Asia’s interview with Korakrit Arunanondchai.) For Raqs, who have curated past editions of Manifesta and the Shanghai Biennale, the current situation has become an opportunity rather than a restraint. Although the trio who make up the artist collective would say that, wouldn’t they? ‘Contact and a state of awareness about being in contact,’ they stated this past April, ‘is the key to a return to safety, without the fear of banishment of the contagious. It is welcoming of different forms and propensities of life.’ Before going on to say that their edition of the triennial will ‘cajole people to see the world as made of liquid states, dissolving and blurring our hold on fixed certainties, making edges dance as centers, where wilderness is not opposed to civilisation, and where there is defiance to the assumed insularity of cultural ethics.’ What that means in practice is an assembly of 65 artist groups and 67 artists, which is going to feel like a multitude after these days of isolation. Look out for contributions by Hanoi-based Farming Architects, performance artist Taus Makhacheva, Park Chan-kyong (whose film Belated Bosal, 2019, on show here, is something of a belter) and a new work by Naeem Mohaiemen. Although, as is the case with most largescale exhibitions, and particularly those curated by Raqs, it will be the works you’re not looking out for that command the most attention.

Much of Berlin- and Mexico City-based Danh Vō’s work has dealt with personal histories and their place within grander worldviews. This summer sees his first solo exhibition in Japan at the National Museum of Art in Osaka (through 11 October). Its title, ōV hnaD, promises it to be appropriately reflective, featuring works made by and with his father as well as a collaborative project made with the family of US Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, one of the architects of the Vietnam War. Vō, who fled Vietnam as an infant in a boat built by his father, winding up in Denmark, purchased a number of the American’s personal belongings at auction, subsequently becoming friends with the late politician’s son, a farmer, who then donated timber from his land to the artist for use in a work. Other works incorporate a chandelier from the Hotel Majestic in Paris, where the 1973 Paris Peace Accords were signed, bringing a nominal end to the Vietnam War.

Over at Ho Chi Minh City’s Galerie Quynh, it’s moon rocks that provide the inspiration for Lunar Breccia (through 25 July), a group show inspired by the classification of concretions created by meteorites that collide with the lunar surface, and by the moon as an instrument for the measurement of time. Working in a variety of media, Hoang Duong Cam, Sandrine Llouquet, Keen Souhlal, Vo Tran Chau, Do Thanh Lang, Hoang Nam Viet and Nghia Dang provide the fragments to be assembled. ‘We are a haphazard bundle of inconsistent qualities,’ the British writer Somerset Maugham once wrote.