Dancing Queen: Women Artists from Asia at Arario Gallery; Looking for Another Family at MMCA Seoul; a Wook-kyung Choi retrospective at Kukje Gallery; and much more

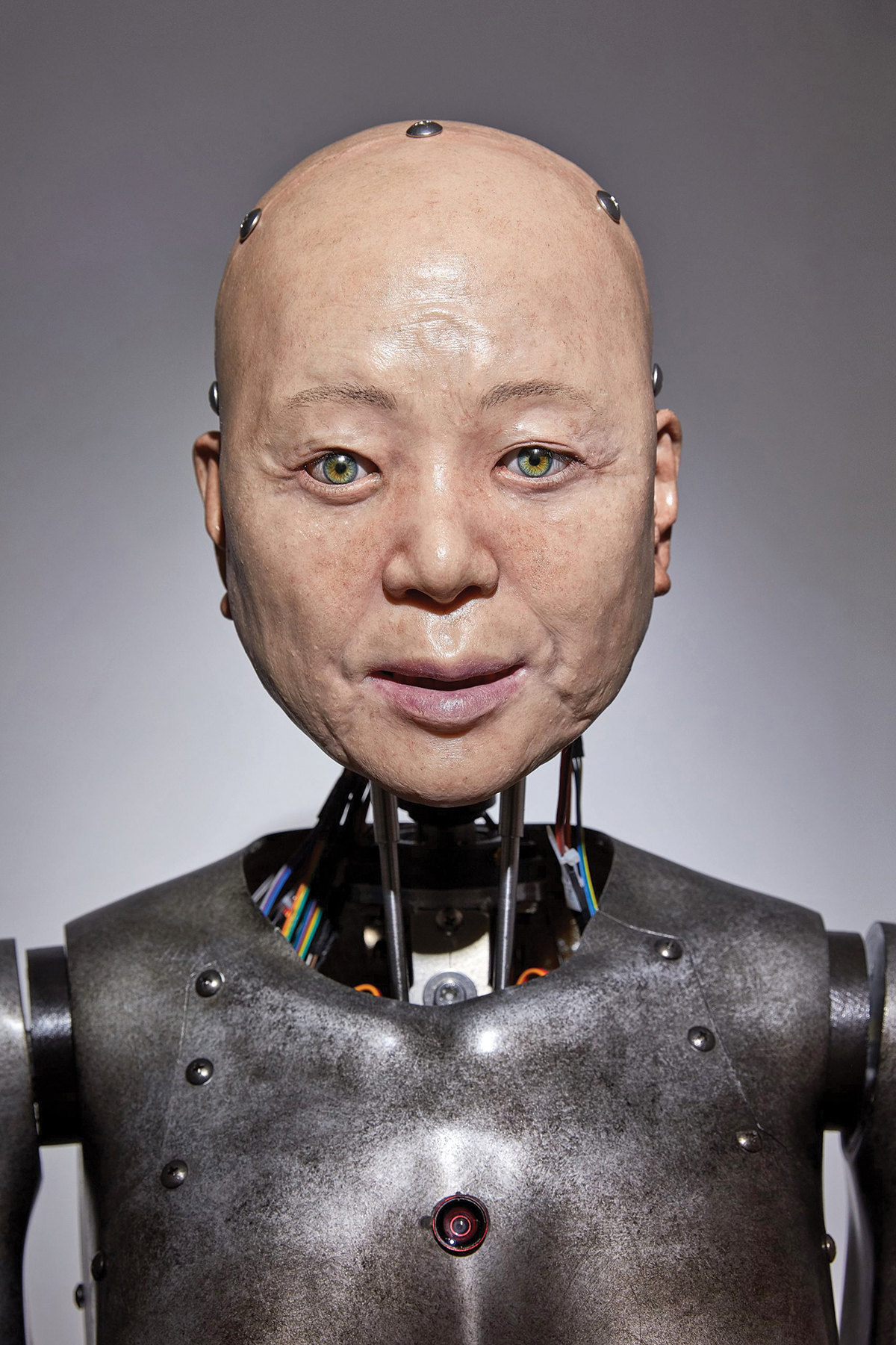

Us Against You, at the Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art, South Korea (through 30 August), is a group show, featuring 13 artists and collectives from East, South and Southeast Asia, about… yeah, it’s obvious: living with other entities. (But you might be glad of the obviousness, given all the talk about ‘invisible enemies’ right now.) It’s about difference and connectedness. The things you’ve been thinking about these past few months. Samson Young is represented by We Are the World (2017), which riffs off the 1980s fad for charity records. A fad that has certainly gained potency in light of the situation that’s currently affecting most of us, one that ironically highlights the looming gulfs between ‘us’ and ‘them’, whether the barriers are cultural, economic or racial. Art Labor (a collective based in Ho Chi Minh City) is showing Jrai Dew Hammock Café (2020), which features, well, hammocks and coffee (murals painted with the stuff), as well as kites created by Jrai people (who live in the central highlands of Vietnam) in collaboration with the American artist Joan Jonas. As a whole it’s designed to encourage a meditation on the changes wrought on the Jrai culture as its relation to the local environment has altered with a move towards industrial (coffee-growing) agriculture. Elsewhere in the show, Korean collective Part-time Suite explores the interactions between AI and surveillance culture, while media artist Jinah Roh’s Mater Ex Machina (2019) travels elsewhere into the realms of AI and its interface with human culture via a creepy robot (a green-eyed bald head with puttylike skin on top of an armour-plated, female-breasted metal torso; limbs absent) that looks like the stuff of nightmares.

Family constructions provide the theme of this year’s instalment of the MMCA’s annual ‘Asia Project’ exhibition, which was initiated in 2017 with the aim (presumably) of placing the Korean institution at the centre of continental discourse about contemporary art. In Seoul, Looking for Another Family (through 23 August) is about expressions of social solidarity in which Asia is repurposed as a family unit. Which feels, ostensibly, like something of an arranged marriage. Or adoption. Eisa Jocson is here with SuperWoman KTV, a karaoke room in which visitors can sing along to tracks by the Filipino Superwoman Band (of which Jocson is a member), mouthing lyrics that describe the ‘emotional labor required of female workers’. ArtReview Asia never does karaoke with its family, but it can see how this might provide some sense of solidarity. Malaysian artist Yee I-Lann’s work primarily takes the form of photography, but here she’s working with a community in Sabah to weave a story of its history and memories in patterned fabrics decorated with iconlike objects, while a trio of collectives, 98B COLLABoratory, HUB Make Lab and KANTINA, have teamed up to produce Turo-Turo (2020, which translates as point or teach in English), a café in which visitors can share food and thoughts. Maybe Art Labor and Akira Takayama will pass by. Connections. Everywhere.

Wook-kyung Choi used to joke about the fact that she was outspoken and angry, and therefore didn’t fit the expected norms of Korean womanhood. She spent just over a decade of her short career (she died in 1985, aged forty-five) in the US, eventually becoming a citizen. A broadly abstract 1966 painting, featuring what might be flailing limbs and an exposed ribcage, is titled La Femme Fâché. ‘My paintings are about my life but I am not simply telling stories. I am trying to express, visually, my experience of the moment lived,’ she once said. A retrospective survey (through 31 July) of this somewhat neglected artist (too often over-shadowed by her Dansaekhwa contemporaries) is on show at the newly renovated K1 space at Kukje Gallery in Seoul (following on from a show of works made in the US during the 1960s and 70s, which took place at the unrenovated gallery in 2016). The current exhibition is split into two parts, the one dealing with her expressive, coloured, abstract paintings and collages (often displaying the influence of the American art scene, from Willem de Kooning to Robert Motherwell) and the other her black-and-white ink paintings (Choi had practised calligraphy while in Korea). Neither East nor West; the work sits somewhere in between.

At Arario Gallery’s Cheonan space, Dancing Queen: Women Artists from Asia (through 11 October) gathers 60 works by female artists from the continent, drawn from the collection of parent company Arario Corporation, which claims to have the largest holding of work by women artists from across the continent. Artworks on show include Makati City-born nurse-turned-artist Geraldine Javier’s The Weight of the World (2013), which combines painting and sculpture to fashion a Skeksis-like angel of death, holding a string of skulls and with rocky crags for wings; Indian artist Reena S. Kallat’s grid of individual facial features, Rainbow of Refuse – 1 (2006); Lee Bul’s ghostly, floating, polyurethane organ-cum-alien Amaryllis (1999, part of the ‘Monsters’ series); and Yin Xiuzhen’s Thought (2009), a bloated brain made up of old blue clothing (part of a series of works in which Yin fashions oversize organs from laundered discarded garments). This last emblematic of the exhibition’s stated aim of collecting individual and collective experience, and rethinking the traditional roles of women in societies across the region. Though, as with many exhibitions of this kind, there is equally a sense that the individual parts, through their responses to particular cultures and regional experiences, might be greater than the sum of the whole.