On the artist’s otherworldly responses to the crises of our time

Over the past 150 years or so, St John’s Island, south of Singapore, has served as an offshore processing centre for undesirables from the mainland. St John’s, or Sakijang Bendera (the Malay name, which has multiple origin stories, literally means ‘deer flag’), has functioned variously as a quarantine station for victims of cholera and leprosy, a detention centre for political prisoners, an opium-addict rehab facility and a refugee shelter.

During the 1970s, however, efforts were made to rehabilitate the island’s image. The land was developed for recreational use and featured holiday camps and chalets. Nature lovers now visit to witness the vibrant wildlife, which includes coastal forests and coral reefs, as well as native birds and marine animals. Today, the island is also home to a multilayered installation by Zarina Muhammad that embraces its history and celebrates its past and present inhabitants – human and nonhuman, immaterial or material. It’s titled Moving Earth, Crossing Water, Eating Soil (2022) and is a part of this year’s Singapore Biennale. And that event as a whole – which occurs at various venues across the country – lurks somewhere between the human and nonhuman, and is named, as you might a child, island or hurricane, Natasha.

In St John’s main administrative building, Zarina has set up a four-pillared structure inspired by saka guru, the central foundation that holds up a building or a roof in traditional Javanese architecture. The area below the saka guru is believed to be sacred and usually treated with certain rituals. Here Zarina has placed a shrine-like arrangement of mystical paraphernalia and symbolic artefacts, which she describes via email as a “a cosmographic map-diorama composed of various material and visual elements that are connected to historical, mythic, speculative and architectural markers on the island and the waters/landmarks beyond her shores”. These elements include a round mirror, referencing a still-standing ‘moon gate’, a Chinese-style circular opening to gardens, erected by German civilians housed there by the British government during the Second World War; an antique tobacco-cutter alludes to the opium smokers; and a gentorag (a brass bell-rattle used in Indonesian music) gestures towards a bell tower previously located at a sentry post on the island’s jetty.

Painted cutouts of eight animals – cat, tiger, dog, bird, mouse, deer, crocodile, fish – are stuck on the pillars of the central installation. These creatures correspond to the eight animals arranged around the cardinal points of a compass found in old Bugis (one of the ethnic groups of South Sulawesi) divination diagrams. These magic charts, on which days of the year could be plotted, provide advice on practical matters; a tiger day is good for marrying or for planting rice, for instance. Besides connecting Zarina’s work to esoteric traditions, these animals invoke a history in which nonhuman archetypes act as a guide for human action.

Moving Earth… contains two key corollaries in Zarina’s works. The first is Southeast Asian mythologies and magic; the second an ecofeminist, Chtulucenic attunement to the entanglements and affinities we have with the nonhuman. What both strands of thought have in common is their decentralisation of the human, especially the human as imagined in the Eurocentric, Enlightenment paradigm of the rational, secular and unitary subject. They each propose radically different modes of nonrational knowledge and of coexistence with all manner of seen and unseen beings.

In Zarina’s work, magic, myths and mysticism, far from being backward superstitions, are put forth as valid ways of navigating a complex and uncertain world. On a practical level, she argues that rituals, charms and spells offer psychological comfort and guidance through difficult times. But her other proposition is metaphysical: that there is a rich and hidden world of ghosts, gods and guardians of which the human is only a small part. This is where a spiritual disposition becomes a sensory issue, of whether one can break out of habitual modes of perception to tune into the rich multitudes of beings all around us, who are our peers in constituting knowledge and worlds.

Spanning installation, film, performances and lectures, the artist’s work often operates in this ritualistic and polysensorial space. Her installations look like shrines or the table of a sorcerer hard at work, filled with sacred offerings and items of religious significance. The mixed-media Talismans for Peculiar Habitats (2019), created during the height of the COVID-19 health-crisis, explored final rites and kinship. Placed on a straw mat on the ground were objects with symbolic meaning in Malay-Muslim death rites, such as sandalwood powder, turmeric and incense used to cleanse and perfume the dead. Elsewhere, a video with watery scenes of tides and shorelines evoked the shifting boundaries between life and death, with water as a gestative conduit for transformation and rebirth.

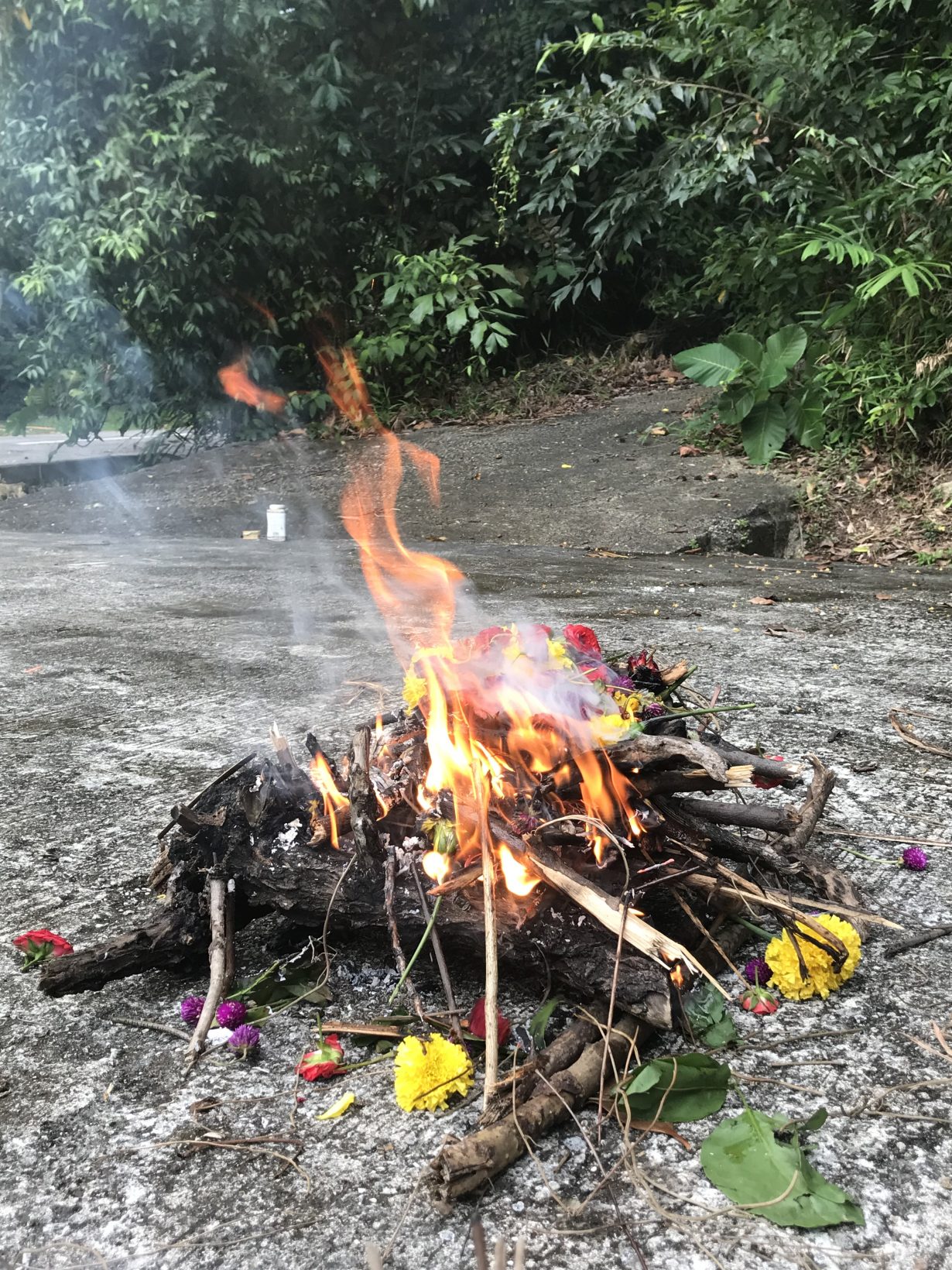

The ‘activations’ of Zarina’s installations are typically participatory workshops taking the form of rituals of thanks and remembrance. For not Terra Nullius (2018), which was situated in 37 Emerald Hill, an old building allegedly used as a station for comfort women during the Japanese Occupation in Singapore, Zarina commemorated the folk spirits of the past and the ghosts of these women. She invited participants to make mutri, ritual offerings, and to place them under an artwork of coloured string and handmade shrines in the garden.

For Zarina, the spiritual aspect of her work is not an affectation or “an aesthetic prop”. She tells me, when we speak by telephone, “I’ve spent the last 12 years researching these realms [Southeast Asian myths and magic], even before the expressions of my work began to be embodied into the category of art.” In the early days, part of her work was inarguably academic in form. For field research, she sat in on exorcism and purification rituals. At conferences, she presented ethnographic papers with titles such as Dancing Horses, Possessing Spirits and Invisible Histories: Re-Imagining the Borders of Magic and Modernity in Contemporary Southeast Asia (2016) and Magic, Belief, Sacred Geographies and Visualising the Unseen in Singapore: Repositioning and Performing the Otherworldly in Southeast Asian Myths and Folklore (2017). Unfolding in parallel were lecture-performances where her scholarly research was re-presented, often with collaborators such as sound artists, dancers and spoken-word poets who were asked to respond to a theme.

Later, as she built up her art practice, she mounted more ambitious mixed-media installations with complex layerings of indigenous belief systems and esoteric knowledge. Pragmatic Prayers for the Kala at the Threshold (2018) was influenced by the Austronesian cosmology of the upper world, the middle world and the lower world, different planes of existence over which specific deities and guardian spirits preside. Jumping off from that tripartite schema, Zarina divided the gallery space into three realms – the hills, land and sea – to represent Bukit Larangan (today known as Fort Canning Hill), Bras Basah, and Kallang and the coastal areas of Singapore, respectively. For each zone, she responded to the histories of the places by displaying a series of found objects, sculptures and effigies created in participatory workshops.

Reclaiming othered female experiences, especially those of wronged, forgotten and nonconforming women, is a running theme. In the lecture-performance Apotropaic Texts (2019), she rehabilitates the figure of the witch, especially the nenek kebayan, a hunchbacked old woman in Malay lore who has variously been demonised as a nefarious, child-abducting, black-magic practitioner or valorised as a benign medicine woman. Also being redeemed in this lecture is apotropaic magic in general, or protection magic that repels evil and harm. She argues that such rituals, remedies and charms are ways of making people feel safe and help them cope with the banal fears of everyday life.

Although currently Zarina seems to occupy a unique magico-religious space in Singaporean contemporary art, it is worth noting that there is a lineage of Malay mysticism in local art-history as practised by artists such as Mohammad Din Mohammad and Salleh Japar during the 1980s and 1990s. A painter and installation artist, Mohammad Din was also a traditional healer and practitioner of silat, a form of Malay martial arts believed to have supernatural powers. He made talismanic paintings and in his later life explored Islamic Sufism through Arabic calligraphy. Salleh, among other things, created paintings and installations using geometric shapes inspired by ancient Malay Muslim iconographies, in response to the loss of traditional culture amidst the rise of the deadening, materialistic values of globalised Singapore.

Zarina’s work carries some of Mohammad Din’s religiosity and arcane knowledge, as well as Salleh’s critique of modernity, but she also carves out a unique position through her feminist and environmental priorities. Just as Mohammad Din and Salleh can be read as reasserting traditional, premodern beliefs in the face of a rapidly industrialising and developing society, Zarina’s concerns can be interpreted as responses to the crises of her time: imminent environmental collapse and widespread inequalities wrought by extractive capitalism, settler colonialism, structural racism and a patriarchal society, undergirded by anthropocentric hubris. ‘Pluriversal’ approaches to understanding non-Western epistemologies, ontologies and practices have sprung up to offer new solutions for development and freedom. Part of this polyphony is Zarina’s blend of magico-ecofeminism from Southeast Asia, which remembers and reimagines connections to the land in its manifold dimensions.

Zarina’s practice expresses her posthuman interest in the ecological and environmental histories of places that might have been overshadowed or displaced by these regimes of power. Her fieldwork takes the form of long walks through such terrain, while attending to creaturely life and the spiritual and psychic traces of the past. Yet it’s one thing experiencing the otherworldly, but another trying to represent it. Rising to the challenge are Zarina’s films, which combine evocative footage of the natural world with text, displayed as lines of subtitles, that spell out a thesis. Breathing in Unbreathable Circumstances (2022), which shows the living things in tidal zones and reefs, proposes a lesson of survival we can glean from other species, which has to do with breathing, finding openings and persisting in intractable conditions. In her text, language flits between the incantatory and poetic (‘we are led by gut breathing, breathing with our skin, belly breathing, tongue-out roaring breathing, the book lungs of arachnids, spiracle breathing, tidal breathing, unidirectional breathing, inhalations at high altitudes, the forms, circuits, pathways of airways, lungs as vessels, the breathing that moves and happens within flood pulses, the sound of breath in a time of breathlessness’) and the literal and prescriptive (‘[all spaces] show us how to unsettle colonial logic, release stubborn attachment to singularity and be attentive to dark matter. Portals are only fearsome if you perceive everything that isn’t you as demonic’).

In general, her sculptural installations, which physicalise her ideas, are less illustrative and cerebral than her text-heavy films. Unbound by language, they metabolise her theoretical investigations into dynamic forms, which engage with the world in more open-ended, spontaneous and unpredictable ways. Part of the multipart exhibit at St John’s Island, for example, is an installation of eight wooden wind instruments in the garden. Elevated on stilts, these handmade instruments have a propeller outside, which can be turned by the wind. The propellers turn a central axis, which in turn moves a series of wooden mallets that strike bamboo plates, releasing light, fluty tones that resemble the sound of marimbas or Indonesian angklung. On the day of my visit, the air was deathly still, and visitors wound up being the ones playing the instruments. The cascading phrases, randomly intersecting in a sort of unintentional free jazz, flowed out all around the trees and up to the sky, creating a song that was different from the natural surroundings and yet belonged to them somehow.

Zarina Muhammad’s Moving Earth, Crossing Water, Eating Soil (2022) can be seen on St John’s Island as part of the Singapore Biennale, through 19 March