William Eggleston is a man of few words. Dressed in a navy suit with a striped bowtie hanging loose around the collar of his white shirt, a pair of freshly polished leather shoes and a sharp side-parting, the 80-year-old Tennessee-born, Mississippi-raised photographer who brought colour into art photography in the 1960s still cuts an elegant, if now fragile, figure. We’re in a hotel room in a ritzy part of London, ahead of a show of his work from the 1970s at a high-end gallery in the city.

We sit in silence for a few seconds.

Eggleston’s work shot to prominence in 1976 when the Museum of Modern Art curator John Szarkowski invited him to exhibit a series of dye-transfer colour images. At the exhibition’s opening, the art critic Hilton Kramer condemned the photographs, writing in the New York Times, that they were ‘perfectly banal, perhaps. Perfectly boring, certainly.’ In 1969, the photographer Walker Evans had declared that ‘colour photography is vulgar’, and although he later retracted the statement (saying in 1974 that he had bought a colour Polaroid and was ‘feeling wildly with it’), his original sentiment reflected the prevailing opinion at that time: that colour photography was more often associated with advertising than with art. Eggleston, who had nearly missed the opening of that MoMA show by falling asleep in his hotel room, has always said that the criticisms never bothered him – that he thought, instead, those critics hadn’t really looked at his photographs. The photographer, who grew up on his family’s cotton plantation, has displayed all the clichéd traits of a maverick; a hard-partier with a penchant for bourbon, cigarettes (Jack Daniel’s Black Label and Natural American Spirit, to be precise) and gun-collecting with no academic training in photography.

Eggleston is more preoccupied with structure and composition than the people or objects he photographs. He calls this ‘photographing democratically’

Travelling the American South – as he continues to do, though his son now does much of the driving – Eggleston would find a spot, jump out of the car and begin shooting images of everything that surrounded him. But for all his seemingly carefree attitude, he has remained insistent on a formal way of looking through his lens, more preoccupied with structure and composition than the people or objects he photographs. He calls this ‘photographing democratically’, meaning that every element of his pictures carries equal importance. On the surface, his photographic aesthetic would come to inform a particular vernacular that describes the American South as made up of freeway signs, gas stations, derelict shop fronts, logos, muscle cars, rusted trucks, and more intimate scenes of domesticity depicted by diner tables and condiments, a shelf of frayed National Geographic magazines, a forest green radiator. Eggleston’s body of work is one of the most significant influences on American visual culture today, cited by photographers and filmmakers including Nan Goldin, Alec Soth, the Coen brothers, David Lynch and Sofia Coppola, its DNA perceptible in the saturated colours of television shows such as True Detective (2014–).

“A few years ago, I did a couple of road trips around America and I realised that what I was seeing, how I was looking at the places we travelled through, was informed by you – among other photographers” I tell him.

“That’s very nice to hear. Thank you.” Eggleston’s voice sounds like a car rolling over gravel, with a clipped Southern accent. After a moment, he raises his eyebrows. “…as well as some other photographers?”

“Stephen Shore, Lee Friedlander…”

Eggleston leans back and nods. “Yeah. I consider Lee Friedlander the greatest contemporary photographer. He did not shoot in colour at all. He didn’t have to. They’re brilliant. Every time I’d look at them I’d think they were in colour anyway. That’s how good he is. We’ve been friends for 40 years, probably.”

“What did you mean when you said he didn’t need to shoot in colour?”

“Oh because the way Lee’s pictures, no matter what format – some are square, some are not – are organised so brilliantly. I think organised is the right word. There are different places which he had wanted to illustrate, where the shapes meet or work with each other. The result is on a very, very high level of consciousness. I think that says enough.”

I ask him if he’d describe his photographs the same way and he smiles, saying quietly, “Yes. I wouldn’t mind at all.”

“In your photographs, the shapes in the composition stand out. Is that something you’re looking out for, something you’re trying to organise?”

“No,” he says, frowning at his knees. “It’s just there. I don’t look for it. It just happens. I think with Lee probably something like that happens as well.”

“Number one: I don’t really have anything in mind. Number two: I really don’t know when to stop, to be honest.”

Eggleston has rejected the term ‘snapshot aesthetic’ – a phrase often attached to street photography in fine art contexts between 1960 and 1980 – whenever it has been applied to his work. Now he reiterates gruffly, “They’re not snapshots. Snapshots are what they sound like. Mine are carefully conceived and confected works of fine art. They couldn’t be more distant from snapshots. If there’s such a thing as a reverse of a snapshot, that would be my work.”

“And why is it important to take photographs of ‘life today’?”

“That says it. That’s just what I wanted to say.” He pauses, then looks directly at me and raises his eyebrows again, “do you think ‘life today’ is not enough?”

“I’m asking you.”

“I think it’s sufficient,” he says comfortably.

I watch him for a moment as he looks at his hands. Eggleston takes time to respond in full; you can see when he’s formulating an answer in his mind, in the twitches at the corners of his mouth, and the way he focuses on the middle distance. But now he won’t say any more. It strikes me that once he’s found a way to express something – say, as wide as the ‘subject’ of his photography – he doesn’t feel the need to elaborate, as if it’s the most obvious answer in the world. So I change gear.

“Can I ask how you produce your series? Do you have a general framework in mind? Do you know when to stop?”

“Number one: I don’t really have anything in mind.” He chuckles to himself. “And number two: I really don’t know when to stop, to be honest.”

After a couple of stalls, it becomes apparent that it doesn’t matter how hard you try to ask open questions: there are some ideas that bite for Eggleston, and a lot that don’t.

I try again. “What do you think is the difference between showing photographs on a gallery wall and publishing them in a book?”

He pauses. “Oh. I don’t think they have anything to do with each other. A show in a gallery is just a temporary thing. A book is not a bit temporary; it’s forever. Let’s open that book there.” He points towards 2 ¼ (1999), which has been lying on the coffee table.

“OK.” I lean forward to pick up the book and begin fumbling through the expansive pages.

“Just anywhere,” he says, unfolding it. Flicking through the leaves, he stops occasionally to consider an image that contains an upside-down rusted car, or purple-and-white flowers growing out of some dusty ground, or a disused Texaco sign lying in the rough. As he looks over each photo, developed from the titular 2 ¼ inch – also known as 120 or 6x6cm – film, it seems as though he’s looking at them for the first time. I’m reminded of when he once described his images as ‘photographic dreams’, ones he no longer remembers a short time later.

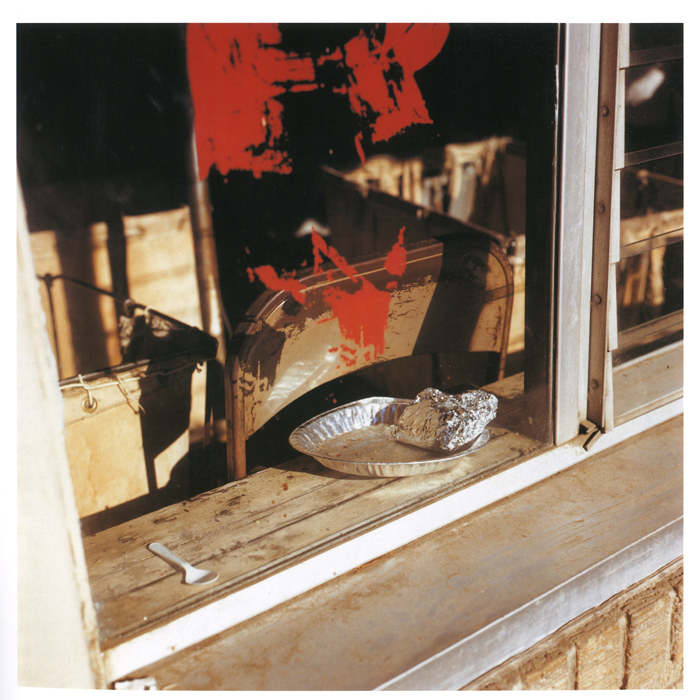

“Here.” He stops at a picture of a windowsill on which sits a used foil pie plate and a plastic spoon.

“A show in a gallery is just a temporary thing. A book is not a bit temporary: it’s forever.”

Diagonal lines created by the windowsill are paralleled a little further in: on the top of the chair’s back, along the edges of what appear to be laundrette trolleys, and in the outline of the sharp dark shadow carved into the sunlit far wall – the contrast of which is so severe, it’s impossible to see beyond the black background. Within the frame, only an ‘R’ can be seen of the scratched-away red wording painted onto the window; the string looping the fabric sides to the trolley frame, the angle of the spoon and the ridges of the pie plate forming a counterbalancing diagonal momentum.

We’ve been silent for a while, so I offer a prompt: “You create your own space with a book.”

“That’s right,” he nods, “right here, right now, we get to really study and pay attention to this picture. At a gallery on the wall, one does not get to spend very much time with it. So we’re experiencing something with this book that a gallery-goer does not have access to.”

When I ask him what’s the first thing he notices when looking back at his photographs, Eggleston again says nothing for a long time. I sit back and watch him, leaving him to think. Eventually, he answers, “I try to study everything about the thing, from every angle,” he places his hand vertically across the page, and then, pointing to different sections, “the way colours work against no colour – those black-and-white areas – which is very important. The subject could be anything. A picture gives it life. As though if it didn’t exist on the page, it would be less.”

He continues, “Say we’re beginning to realise, because we keep looking at it, that this is really complicated. It’s not a simple thing. But in a gallery you don’t have the time we’re taking to keep looking and analysing everything in the frame. It’s simply that we need to do that. And being in a book allows this.”

We fall silent again, looking at the photograph. As Eggleston’s concentration intensifies, it looks as though he’s taking every detail in the image and atomising it, looking closer, and still more closely. And then it occurs to me that when he said, in 1988, that he was ‘at war with the obvious’, perhaps it wasn’t about elevating the everyday, the banal, into something ‘important’. Perhaps he really is fighting the obvious: those parts of his photos that people are most likely to centre on; those identifiable cultural markers that suggest a narrative – as when his work is associated with the American Gothic. Instead, his photographs, which are often arranged geometrically – either grid- or flag-like – contain compositional balances, as seen in another picture in 2 ¼, in which busts of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy sit on a bar shelf surrounded by bottles of bourbon, vodka and rum. Here the grid is formed by the shelves, wall cladding and ceiling tiles, but repetitions also occur in the three bottles of liquor lined up on the shelf below the busts; in the square photograph positioned next to a mirror of the same shape, and below that, the till with its grid of buttons.

You could call him a formalist, if you wanted to put a label on him, but here, now, watching Eggleston quietly study his own picture, I think about the way he stresses the word ‘everything’, and wonder whether he is looking at his photographs and trying to understand the nature of things on the smallest possible scale.

“Do you hope that people see everything in your photographs?”

“Hopefully,” he says, “but I don’t think it happens too often.”

“The subject could be anything. A picture gives it life. As though if it didn’t exist on the page, it would be less.”

We pause again, before discussing the colour red, which is ubiquitous among Eggleston’s photographs. He tells me it’s a powerful colour, and that it doesn’t “like” other colours. “Red has power. It could be other things too. I can say that right off easily. It’s so powerful you don’t really need much of it. There are certain pictures and paintings that are completely of red.”

I think of his photographs of dusty red brick surfaces and painted tin roofs, of a red truck shot close up so that it nearly fills the frame (in the silver bumper, a tiny reflection of Eggleston can be recognised) and, of course, the stark Greenwood, Mississippi (1973) – a photograph of a ceiling with a bare light bulb trailing white wires which he described ‘like red blood that’s wet on the wall.’

“Including your own.”

“Mhmm,” he nods, with a slight rock back and forth. “That’s so much true. It’s pure – and I think that constitutes where its power comes from. Pure red does not contain any other colours. That is not unique, because other colours, primary colours, are pure.”

I can’t tell if this talk of ‘purity’ is just about the colour red, or if Eggleston is also, maybe, talking about himself. He has historically stood apart from his contemporaries both in the sense that he was never formally trained and in his resistance towards being categorised: he wasn’t included in ‘groups’ of photographers like those who showed in seminal exhibitions such as Szarkowski’s 1967 MoMA exhibition New Documents (Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander), or William Jenkins’s New Topographics at George Eastman House in 1975, which included Robert Adams, Stephen Shore, Bernd and Hilla Becher and Lewis Baltz. When I ask him about this, he simply says: “I don’t like their works.” I don’t point out his contradiction on Friedlander, instead asking him whether he sees himself as an outsider.

“I don’t know…” he says, gazing straight ahead. “I don’t think you have to study to understand the way art works. In fact I’m not sure it’s such a good idea.” And then, in a conspiratorial manner, he grins, nudging me. “It might be better when you figure it out yourself.”

We settle into a comfortable silence, and Eggleston returns to the picture of the windowsill on our laps. In another interview a couple of years ago, he spoke about his other interests, in drawing, painting and making music. (In 2017, he released an album of improvisations played on a synth that were recorded on floppy discs and cassette tapes in the 1980s.) At that point, he’d said he might like to start writing, so I ask him whether he ever started.

“No,” he shrugs, “things that are images within the field of graphic arts and words do not mix. That’s why I don’t like to put words with my images. They just don’t belong together. I don’t think words are powerful enough to ‘restrict’ any image. But they certainly don’t help being around.”

“I don’t really think there’s any connection,” he continues earnestly. “It’s often thought by lots of people that there’s every kind of connection in the world – well, they’re wrong. There isn’t. I know I’m right in saying that. I may be laughing right now, but it’s no joke!”

I ask him how he thinks his photographs communicate.

“Only if you study each one intently and using all of the intellect to decipher the image or observe every single thing that’s going on in it. I have to use the word decipher because, to view them on the surface is like considering them snapshots, which they are not.” He points to the photograph, “This is deeper.”

I sit back again, looking at the sun’s reflection in the shine of the foil pie plate.

“Do you keep looking at your pictures?”

“Yes, absolutely.”

William Eggleston: 2 ¼ is on view at David Zwirner, London, through 1 June

From the May 2019 issue of ArtReview