“Imagine an impossible room,” the voice tells you. “A room that’s impossible to inhabit, and thus to observe. Can you see it? No door, no windows, no ins and outs, and no fourth wall – absolutely no fourth wall.” The clipped male voice, narrating James N. Kienitz Wilkins’s short film This Action Lies (2018), speaks over a black-and-white image of a Styrofoam cup full of steaming coffee. It’s the only image provided during the half-hour, pun-laced rant on appearance and reality. It describes itself as an “apology” for the “production and consumption of movies”, but instead ends up describing the history of Dunkin’ Donuts advertising slogans, the interruptions of new parenthood and the thought experiment above, concluding, “It’s not really about observation, you see, aside perhaps from observing the limits of your own mind”. Like many of the American artist’s films, This Action Lies is defined by its narrator, a dominant voiceover that manoeuvres smartly on top of relatively static imagery, mocking the tropes of mainstream cinema (drama, tension and that gravelly, male movie-trailer voice), all the while making ironic use of them. His description of the imaginary room also neatly depicts our own relationship as the audience to much of current artists’ video output: looking in through the imaginary window of the screen, our vision guided by a narrator.

The current predominance of voiceover in artists’ video has been several years coming. We can trace its lineage back through the singular narrators of oral storytelling traditions and the novel, and the supposedly matter-of-fact voiceover of documentary film. But the proliferation of video art since the 1960s wasn’t accompanied by a deluge of voiceover. It’s a more recent phenomenon that has come with a dawning awareness of infinite perspectives and relative truths, which found its popularity in art at some point after Kevin Spacey’s voiceover from the grave in American Beauty (1999) and the BBC-newscaster-turned-conspiracy-theorist tone of Adam Curtis’s The Century of the Self (2002).

In the age of monologue, everyone is angling to speak over, on top of or past each other, just not to each other

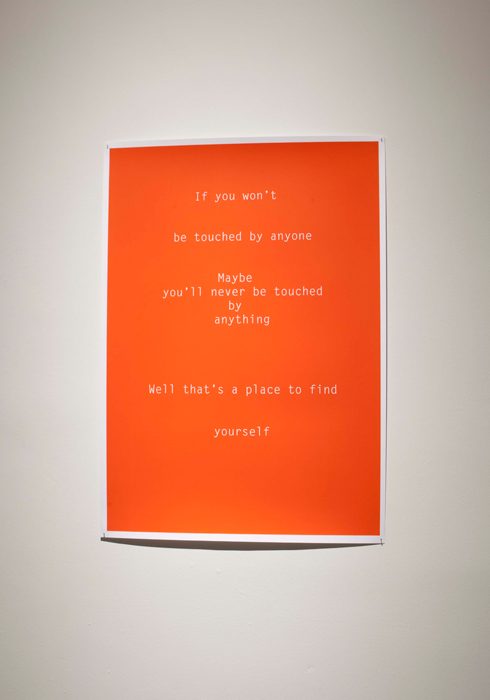

It’s no longer one aspect used to highlight the particularities of experiencing the moving image, like the offscreen director of John Smith’s The Girl Chewing Gum (1976); it’s now the default. At the time of writing, a quick survey finds art by Jamie Crewe, Alex Da Corte, Wong Ping and Zoe Williams on display in London using the method, while recent works by Ed Atkins, Lawrence Lek, Laure Prouvost, Elizabeth Price, Fiona Tan, Bedwyr Williams and Rehana Zaman readily come to mind, as well as last year’s Turner Prize winner, Charlotte Prodger, and 50 percent (Helen Cammock and Tai Shani) of this year’s Turner nominees. Danish-Iraqi artist Masar Sohail won the 2018 Dorothea Von Stetten Award with his short film Republic of TM (2016), in which a young man imagines setting up his own utopian state in a forest – all told with a ridiculous accent impersonating Scarface’s Tony Montana. The voiceover is, in skilled hands, of course used for a reason, as a means to reflect on authority, presence and subjectivity; but its popularity is also symptomatic of a wider cultural moment. The rise runs parallel to that of clickbait op-eds and online rants, of blatantly biased newscasters and populist rallies that all coalesce to create a fractured, kaleidoscopic sense of noninteraction. In the age of monologue, everyone is angling to speak over, on top of or past each other. But not to each other. Everyone is talking, then. But is anyone actually listening?

Tai Shani, Semiramis, 2018, performance and installation at Glasgow International 2018. Courtesy Tramway, Glasgow

The voiceover is a classical voice of authority: like a public speech it provides the easiest and most economic means to deliver, and control, a story. Just think of the straight-up documentary narration of William Raban’s Thames Film (1986), or the more literary narrator of Patrick Keiller’s ‘Robinson’ trilogy (1994–2010), calmly relating his titular character’s esoteric mapping of the UK. But several artists, including Kienitz Wilkins, Cammock, Prodger and Shani, are currently grappling with it as the primary means by which to undermine that authority, and as a vehicle through which to ask if there’s any way to escape the echo chamber of the monologue. Throughout their work, the voice is used to pointedly diverge from the images presented to us, creating a tension that meanders, manipulates and mutates what it is that we think we’re experiencing.

At one point in Shani’s epic Dark Continent: Semiramis project (2018), we encounter another imaginary room: “The chamber has no windows. There is only a small door to enter through. Inside, the ceiling and walls are horror vacui,” painted in “an arcane flesh-tone palette of peach, flush, rose”, all looking over a torn dress splattered with blood. Such carnal, Gothic imagery runs across the 12 episodes of Shani’s project. But most definitively of Semiramis is that all 12 parts – each dedicated to a single character, among them a vampire, a cube of flesh and a mirror – are narrated over the accumulative five hours by a single female voice. Originally a series of performances at the 2018 Glasgow International festival, recorded and since exhibited as videos, the whole thing is staged on a surreal tableau of floating columns and giant hands: the fictional city of Semiramis, built and inhabited by females. Although actors physically embody the various characters, they remain silent and mostly still, the voiceover providing the main animating impulse, in the form of soliloquies submerged in the perspective of each character in turn, describing pulsing desires and psychosexual transformations, revelling in sensory contradictions. Despite all these points of view, touching on references ranging from Christine de Pizan’s medieval feminist text The Book of the City of Ladies (1405) to Beyoncé lyrics, the uniform narration has a flattening effect: warm, but still aloof and steady, with the measured formality of Greek theatre. This is, perhaps, part of the point: the narrator of Semiramis is an unapologetic corrective, a direct takeover of the classic narrator role; speaking over all the supposedly objective male narrators of the past. In The Psychic Life of Power (1997), philosopher and gender theorist Judith Butler described a ‘strange scene of love’. Attempting to parse the psychological workings of French Marxist theorist Louis Althusser’s concept of interpellation, she found concealed a masochistic desire for being directed, scolded and lectured by the authorities, so that a person’s existence be given the most basic sign of recognition. Althusser had proposed interpellation only summarily in a 1970 essay, as the mechanism through which individuals were folded into ideological systems: being hailed, called to, and, in turning to acknowledge the call, becoming enmeshed in a hierarchical relationship. In his limited writings on the subject, interpellation is presented as a sort of straitjacket we put on ourselves: an inescapable self-entrapment. Or, in the tongue-tying way Althusser described it, ‘a subject by the Subject and subjected to the Subject’. The voiceover is a form of interpellation: by listening to it we are imbricated into a temporary contract with the speaker, submitting ourselves to its world – but through that, if we apply Butler’s theory, potentially finding some way of having our own contours recognised. Butler questioned where the person being hailed sits in all this: ‘Who is speaking? Why should I turn around? Why should I accept the terms by which I am hailed?’ Althusser had died in 1990, disgraced after murdering his wife in a bout of severe depression; but it seems within the idea of interpellation Butler found embedded questions of choice, responsibility and civics, how we might converse or cooperate through or despite the ideological codes we negotiate and are imprisoned by within every social encounter. The sheer mouldable potential of our existence, she concluded, exceeds being entirely trapped in such a bind – but the bind remains all the same.

Such contradictions run along the open seams of the recent video installations of Charlotte Prodger. As the narrator states in Stoneymollan Trail (2015), “we always, we always, we always have a story”. It’s just in how we tell them, the means and tone through which these stories are shared, that open up the fact within the fiction: that authority is a negotiation. In her work SaF05 (2019) at this year’s Venice Biennale, a film crew and guides ostensibly attempt to track a female lion that has been displaying male tendencies. Like most of Prodger’s videos, though, the footage consists primarily of travelling – hiking, driving, the view from a train or airplane – while the voiceovers act like a wayward attempt at affixing thought to these passing places. Lists of technical details are contrasted with confessional disclosures, as if reading from a notebook that has a filmmaker’s shot list on one page and intimate diary on the other. A snow-covered hill rolls by in front of us, as the narrator recalls showing a friend pictures of a sculpture on her phone at a party, accidentally scrolling too far to an image of her lover, “on our bed with a clear glass butt-plug inside her”. The disclosure to us parallels the shocked moment, an unexpected eruption of privacy into the open. But between Prodger’s disjointed dictations and wanderings is a trusting entreaty: that we assemble our own version of the character that the various parts of the video might represent, and perhaps recognise that we, as entities sharing time and space, are only similarly assembled from such incidentals.

The means and tone with which stories are shared open up the fact within the fiction: that authority is a negotiation

In the work of Helen Cammock, this issue multiplies, spreading along historical fault lines. Her videos, prints and installations demonstrate a preoccupation with how to give voice to those who have been overlooked or forgotten; and to multiple, contradictory perspectives. There’s a Hole in the Sky Part I (2016) is narrated entirely by the artist, the script culled from interviews with activists and workers, and from readings by black writers such as James Baldwin and Jamaica Kincaid. Stories of the Nicholas Brothers, whose dance moves made people like Fred Astaire famous, or of the sixteenth-century heiress Beatrice Cenci, who murdered her abusive father, are given space to resurface in the present. More recent works, such as The Long Note (2018), draw directly on documentary film methods, incorporating talking-head interviews alongside extended sequences where Cammock speaks over footage, at times as herself, occasionally as others. The Long Note focuses on making known the key role women played in the Northern Irish civil-rights movement. In the penultimate scene of the video, she speaks both to and for one of the women involved: “And you were young, and you wanted to be inspired, and you were angry, and you were starting to realise you wouldn’t make this right if you didn’t find yourself a part of what was happening”. Cammock’s voiceovers present a fractured self that jumps between various ‘I’s and ‘you’s, embodying and making heard a range of voices. The ‘you’ also becomes the audience, putting us on an equal level as whatever ‘I’s and ‘they’s that make up the stories we’re told; it becomes our own responsibility to find ourselves a part of what is happening.

Voiceovers attempt to create a consensus of a reality between the speaker and the listener, however fleeting or fabulist. Consider the doubling, punning unreliable narrator of Laure Prouvost’s films, speaking about her fictional grandfather in Wantee (2013), or Lindsay Seers’s search for her missing sister in It has to be this way (2009). Throughout Kienitz Wilkins’s work, there is an obsession with the ‘real’, and an insistence on trust, imploring that we believe what the antsy narrator is telling us. “I’m trying to tell the truth, nothing but the truth this time,” he states in his short video that also mimics a self-conscious film pitch, Indefinite Pitch (2016). Each generation of moving-image makers adjust their version of realism according to what will impact on the audience, from cinéma vérité to Dogme 95, and there’s a certain relative realism in the popularity of voiceover as reflective of our current culture, where the monologue traps us in a closed-off, impenetrable room. Though as Cammock, Kienitz Wilkins, Prodger and Shani suggest, the conscious emphasis on voiceover isn’t just a postmodern tool, nudging at the fourth wall, but both a means and an end for particular articulations and negotiations of how we understand gender, race and our own agency in social contracts; how we hear and listen is just as important. Academic Jacques Bidet, writing on Butler’s take on interpellation, describes it as ‘amphibolous’ – capable of two meanings – that the call isn’t just a one-way directive, but multivalent; it can also be misheard, misinterpreted and misused. Which perhaps makes it like any other speech act; but this isn’t just about learning to put up with people droning on and on. These artists’ uses of voiceover don’t offer a solution or an escape from the age of monologue, but are a conscious sounding-out of its limits and strata, using the monologue to ask us what, if anything, is the appropriate response.

Work by Tai Shani and Helen Cammock is featured in the Turner Prize at Turner Contemporary, Margate, 28 September – 12 January; Charlotte Prodger’s work can be seen at the Venice Biennale, through 24 November, and in Palimpsest, Lismore Castle Arts, Ireland, through 13 October; James N. Kienitz Wilkins’s solo show is at Spike Island, Bristol, through 8 September

Chris Fite-Wassilak is a writer and art critic based in London

From the September 2019 issue of ArtReview