“I call myself an offset artist,” says Dayanita Singh. Anyone who follows contemporary art closely knows her as one of India’s leading photographers. Yet, as we talk over a video link (she is in New Delhi, the place of her birth and a city she has called home, periods of study in Ahmedabad and New York aside, ever since), she makes the statement with an ease and certainty that I can only imagine comes from decades spent trying to figure out where she fits within the traditional parameters of being a ‘photographer’. And, to be fair to her description, the printed book is her primary exhibition format.

Although Singh grew up surrounded by the photographs and family albums made by her mother, Nony Singh, who is also a photographer, her initial studies were in the field of typography, fuelled by an ambition to create new fonts that would better reflect the diversity of languages spoken in India. It was, appropriately, a book, and more specifically an assignment to produce one during her first year at university, that led her to the medium with which she is now identified. She tells me she thought that if she could quickly photograph the famed tabla player Zakir Hussain during a concert in Bombay for this homework, she could then spend the rest of the evening partying in the city. It’s a story she’s well versed in telling: an organiser at the concert told her not to take the photos, then pushed her away. She fell in front of a hallful of people and was left humiliated. Yet the second part of the story reveals something about Singh, not as a photographer or artist, but as a person: her tenacity and defiance of expectations, both professional and social, that would drive her practice for the next four decades.

“I went outside and I waited for Zakir Hussain to finish the concert,” she recalls. “He came out and I put my hands on my hips, and I said, ‘Mr Hussain, I’m a young student today. Someday I’ll be an important photographer, then we will see.’” She was eighteen at the time, and after accompanying Hussain on tour for the next six winters, in 1986 she produced her first photobook, titled after her subject, as her final degree project.

The photographs in that book became more than a series of concert shots, instead forming an in-depth study of Hussain – with images of the musician during his practice sessions and concerts set alongside intimate scenes at rest and with his family, captioned with Hussain’s handwritten notes and printed alongside excerpts from interviews between Singh and the tabla player.

“I realised if I could just say ‘I’m a photographer’, then I could go wherever I liked. I could travel with whomever I liked. I didn’t have to be answerable to anyone. I just invented the role of photographer for myself so that I could be free and not get boxed in by marriage or family or gender or artform or nationality. I hate all of that.” When she decided to study at New York’s International Center of Photography, Singh asked her mother to use the money that had been set aside for her dowry to pay the school fees. Nony, keen that her four daughters be financially independent, granted her eldest daughter Dayanita that wish. This independent streak, encouraged by her affluent and comfortably liberal upbringing, freed her from the social constraints of the time.

While she studied the work of, as she calls them, the “American masters of photography” (she means the likes of William Eggleston and Garry Winogrand), she says that none, bar Robert Frank, had a direct influence. Instead, inspiration came, and continues to do so, from music and literature. “I use literature to get out of photography,” she is fond of saying. She mentions Rainer Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet (1929) – specifically the first in the series – in which the poet writes that a work of art will be good when it arises out of a necessity to create, and finds inspiration in the personal and the everyday.

That line of thought translates to the pictorial work of Singh, who additionally chooses to give less importance to the individual photograph as a work of art, treating it more as a raw material, like ink or paint, that can be applied to an object. “Photography in itself is just not enough,” she says. “We have to do more with it. I knew from the beginning that the book was at the heart of my work. That’s all I wanted to do.”

By calling herself an offset artist, Singh sets herself apart from the categories of ‘photographer’ and ‘publisher’, but at the same time situates the output of both those professions within the artworld. Further, as the dominant form of processing large print-runs, offset printing is a cost-effective way of making books that allows Singh to experiment with the way they might be bound – as well as to challenge how art, especially that which can be printed to demand, is ultimately valued in the context of that artworld.

But when she says the book is at the heart of her work, Singh’s development of the form suggests that it’s more than just the primary output of her practice. It seems essential. As if the book is not just a means of presenting her work, but represents something that, for Singh, is alive and evolving, expanding the medium of photography beyond the frame of the image.

We discuss the current position of photography within the artworld and she is quick to criticise how contemporary photography exhibitions are “fossilised”, stuck in the mode of showing photographic prints on a wall. She says when she first began showing silver gelatin prints in wall-mounted frames, she felt stifled: “There must be other ways of sharing that work. We cannot follow the dictate of a museum or a gallery space on how photography has to be seen.”

This frustration at the lack of innovation in the medium, coupled with the desire to change how photography is experienced in museum spaces, has led Singh to eschew that conventional method, and instead find ways to fill the negative spaces of a gallery with her book objects, boxes and ‘museums’. “I love the book, but I also love the museum space, and I wanted to find a way between the two – a third space. So I started to make my book objects,” she says. “I always felt that I wanted the book to be the exhibition. I wanted to slip the book into the frame so that people would know that even if they can only see one image, I have a whole symphony that I created around that image,” she explains, referring to File Room Book Object (2013), an exhibition series that is the product of File Room, a book published the same year. It’s the first book Singh published with a series of different covers, each bound with a different colour cloth and showing a unique image – a format that was followed by Museum of Chance Book Object (2015), which was published with 88 different photographs that appeared on the front and back covers in random pairs – a decision that places those books somewhere between a unique art object and a mass-produced edition.

In 2012 Singh presented her first ‘museum’, also bearing the title File Museum, in which black-and-white photographs of the paper archives of government and municipal offices are presented inside the windows of a large teak structure that can be opened up via hinged panels to reveal smaller structures that make up storage space for yet more photographs (there are 140 in total) from the series inside. It’s a homage to archiving, storing and arranging, and one that also reflects on Nony Singh’s practice of photographing and collecting pictures of family and friends. Dayanita prefers not to show work chronologically but instead draws from her own extensive collection of photographs taken since the 1980s. Since then, her ‘museums’ have expanded to incorporate desks, stools and even a bed (Museum Bhavan, 2013, and Museum of Shedding, 2016), all of which can be safely enclosed by the main structure. Her most recent installation, Pothi Khana (Archive Room, 2018), was shown at the 57th Carnegie International, and consists of modular columns that contain images taken inside an archive of papers wrapped into cloth bundles, desks piled high with documents, shelving units and filing cabinets, accompanied by wooden stools. Singh intends to show this work at an upcoming solo exhibition in London, but, ever looking for new ways in which people might experience her work, has decided to reconfigure it.

Searching for new ways to present her books – ways that mean they can be shown outside of the museum context – Singh launched Spontaneous Books as an unconventional ‘publisher’: “If the forms don’t exist for it to be displayed the way I would like to display it, I can make those forms myself.” Instead of the traditionally printed and bound book, she began to make teak boxes. Singh started with Kochi Box (2017), a collection of 31 photographs printed on card and kept within a box that has a window cut out on the front to display just one of the prints at a time. When presented at an exhibition, 31 boxes are on display, each showing a different photograph resulting in countless combinations, but Singh also has in mind the way someone might choose to show it in their own home; whether they have one box or three, that someone becomes the curator of their own miniature exhibition of Singh’s works. By transferring agency to the viewer, Singh, apart from choosing which images to include in a series, relinquishes control over how and in what order the viewer interprets them, and in this sense reduces the importance of the subjects of her photographs.

‘We’re constantly changing as people, nothing is static, so why shouldn’t the work change with us?’ Singh said in 2013, referring to Museum Bhavan during an interview with The New York Times. It’s an ideal she applies to all of her works. For her most recent box series, Box 507 (2019), commissioned by the Geoffrey Bawa Foundation to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Sri Lankan architect’s birth, Singh tells me that by making her own alterations to an offset printer (“You could say I remove two layers from the print”) so that the resulting images are rendered more like pencil drawings, she has been able to further remove her presence from her photographs.

At the opening reception, Singh recalls, “Most people were like: ‘It doesn’t even look like Dayanita’s work’. I was really happy. If 20 people had come and said, ‘This is amazing’, I would be worried because I would think that I didn’t really make a step forward or a step away from what I was already doing.”

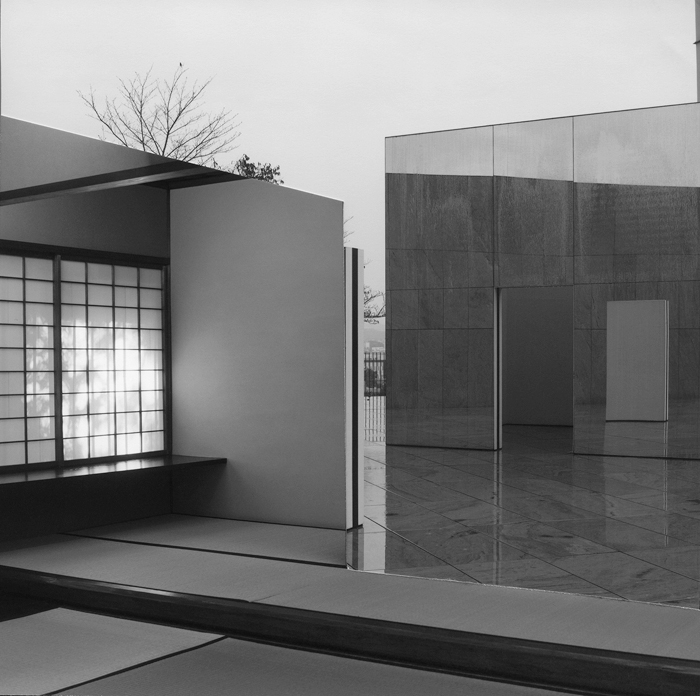

This pursuit of new forms, of making a step forward, has led to her latest work – a collection of photographic montages. Each work in the series is built up of architectural photographs that are structurally composed in a manner that reads as an actual building, until you realise that you’re looking at interiors spliced with exteriors in a way that appears seamless. Cut pieces of black-and-white photographs of columns, windows, facades and sections of rooms are set alongside each other, the gaps and spaces between their locations made barely visible by the thin lines that divide them. Singh has written before about the inspiration she takes from Japanese writer Junichiro Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows (1929), in which he describes the merits of darkness in architecture, as a method of introducing the unknown or mysterious, as an element that obscures – and that mode of thinking translates to the way the montages leave you accepting the strange new spaces that you, as a viewer, are drawn into.

It’s part of what makes it difficult to pinpoint the subjects of her photographs, and Singh is adamantly against offering any kind of straightforward narrative. To try to describe any image in depth would be to single out or elevate it beyond the others, and the longer you spend with her works, the more you realise that the photographs in each book, object, museum or box should be considered as if they were a collection of everyday records, a messy and chaotic mixture of people, places and experiences, fact and imagination.

Circling our conversation back to past influences, she tells me that apart from the Swiss-American Robert Frank (who produced the documentary series The Americans in 1958), she didn’t really look to other photographers. Instead she credits her best friend of three decades, Mona, a eunuch she met who lives in a graveyard and about whom she made a book titled Myself Mona Ahmed (2001), which evolved from a photojournalistic assignment into a more intimate portrayal of her friend’s difficult life. She says she finds inspiration in the way Mona has chosen to live “outside of the system” – that system which dictates societal ‘norms’. And of course, Hussain, who Singh refers to as her mentor and from whom she learned about sequencing, pace, tone and perseverance. “I think classical music became the biggest influence and I would say my training is not as a photographer. My training is really how to be an artist, how to live the life of an artist. The focus, and rigour, and disappointment, all of that, I learned from Zakir. He made sure that I stayed with photography,” she explains.

Singh often uses musical terminology to describe her practice, and when I mention that the way her work slips between different forms of presentation, finding its own space somewhere between a book and exhibition, or how the photographs hide any concrete narrative, or the way she evades being categorised as an ‘artist’ or ‘photographer’ by calling herself an offset artist reminds me of the microtones found in various musical traditions – the unnameable ones that slide between each note of a scale – she smiles and says, “That very intense training from Zakir, and being around musicians for six years, allowed me to find my own microtones. But I’ve also written about the empty note, the khaali. It’s a gap between two notes, but it’s also a note. It has its own place. I don’t usually get into it because it’s difficult to explain. The secret really is in withholding, like a great musician knowing when to stop and how not to reveal the whole thing. It’s what’s unsaid, and if I could say it, then why bother photographing it?”

Work by Dayanita Singh is on show at Frith Street Gallery, London, through 9 November. Zakir Hussain Maquette, Singh’s first photobook, is republished by Steidl in September

From the Autumn 2019 issue of ArtReview Asia