Gwangju, South Korea: people died for democracy in May 1980. After the assassination of president Park Chung Hee in October 1979, a military coup led by Chun Doo Hwan (who served as the official president from September 1980 to February 1988) sparked unrest among university students across the country. On 15 May 1980, around 70,000 students from 30 different universities staged demonstrations in the city of Seoul, protesting against increasing censorship and a lack of freedom in education. Three days later, on 18 May, 600 students gathered in a similar protest in the centre of Gwangju. Some threw stones at the 7th Special Forces Brigade stationed there. The army’s response was to bludgeon, arrest and open fire. Following this, thousands more civilians were moved by the violence of the armed forces to join the pro-democracy protest, taking up arms themselves in a city-scaled insurrection.

Official figures from the Korean government state that 200 people were killed, but other sources suggest that the number might be more like 2,000. Today, families of victims are still searching for the truth about the deaths and disappearances of the lost.

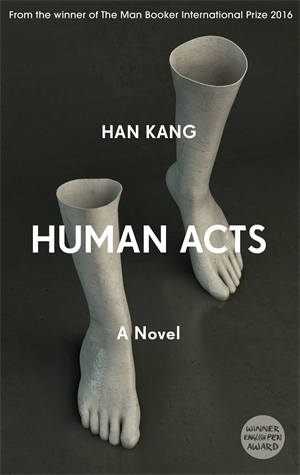

In the seven chapters of Han Kang’s newly translated literary nonfiction, seven experiences are obliquely connected to one: that of fifteen-year-old Dong-ho. Following his search for a friend who went missing after the May 18 attack, we meet other people, whose stories are told, sometimes indirectly, over the following chapters. Dong-ho, his unnamed mother, Jeong-dae, Eun-sook, Jin-su, Seon-ju, ‘the Prisoner’ and ‘the Writer’ – they can’t be called characters because the book is based on archival material and conversations with real people.

Each chapter is carefully positioned, told not just for the sake of maintaining the web of tied experiences, but because each name represents something much broader: the limits to which the human body can suffer and the point at which a soul breaks. The book tells of the fight for democracy, of military violence and of government censorship through the stories of individuals and their relationships with one another. But what gives Human Acts such profound weight is that Han Kang addresses the trauma from these accounts with the kind of brutal honesty they deserve. The emotional and physical scars of the people who survived the Gwangju Uprising remain etched in the back of my mind long after I finish reading it.

From the first chapter, Han establishes the reader’s role as participant and observer. Using a second-person narrative, ‘you’ become Dong-ho and you are caught in the middle of the uprising. You appear in other chapters too, moving through different bodies, watching and listening as people struggle, disintegrate, lose hope, stop living. Through it all, the dichotomy of the soul and body pervades: ‘When the body dies, what happens to the soul?’ Dong-ho asks. ‘How long does it linger by the side of its former home?’

She doesn’t spare the reader the explicit and the traumatic (the Prisoner’s chapter, in particular). The detail with which Han describes decaying bodies, mutilation, broken souls and grief is at once emetic and – though curiously and to great effect, distanced – almost objective. If the last chapter, which presents Han’s own connection to and research into the web of relationships that comes before, seems like it might be in danger of wrapping the various narratives up a little too neatly, there is one story conspicuously left out.

The recurring image of a girl’s rotting, unidentified and unclaimed body (whose origins, we learn, were the inspiration for the book) becomes a universal trope for the human capacity to perform great acts of violence – and to continue to commit them over and again. A symbol of ‘many thousands of deaths, many thousands of hearts’ worth of blood’, Human Acts hurts to read.

This article first appeared in the Autumn 2016 issue of ArtReview Asia.