In July 2015, Para Site launched the yearlong Hong Kong’s Migrant Domestic Workers Project in order to ‘build connections between the artistic community, the city’s wider public sphere, and the domestic worker community’. Although they make up 4 percent of Hong Kong’s population, domestic workers are largely under- represented in its politics.

In 2013 the Hong Kong government ruled against granting Foreign Domestic Helpers (FDHs) the right of abode, regardless of the number of years they had been in service. Foreigners working in other professional sectors are allowed to apply after seven years of employment. Not having any base outside of their employers’ residences (in which they are legally required to live), the mass Sunday-picnics below the HSBC headquarters and in the financial district’s surrounding parks are a visible reminder of their presence and status.

The idea behind the initiative, therefore, was to raise awareness of the issues facing the city’s largest minority group by setting up the subproject A Room of Their Own, in collaboration with KUNCI Cultural Studies Center, which had begun research into the lives of Indonesian migrant workers, and which set in motion The Afterwork Reading Club/ Klub Baca Selepas Kerja. Between 2015 and 2016, the reading club ran six sessions for Indonesian domestic migrant workers (some of whom are also writers) and resulted in an agreement that Para Site would fund rental spaces for a mobile library (the subject of a text by migrant worker Aiyu Nara) at which FDHs of different nationalities could share a cross-cultural literary space as well as learn about their legal rights.

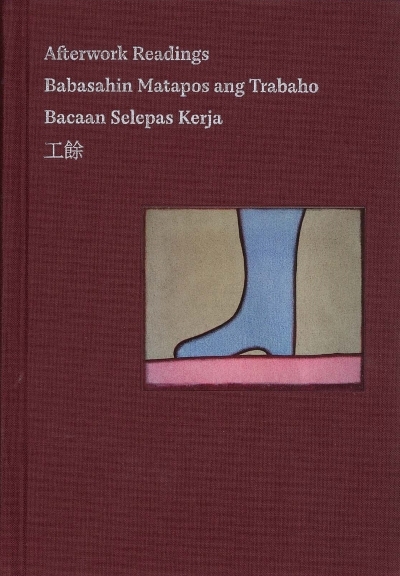

Concurrent with Para Site’s spring exhibition of works by both artists and domestic workers, and developed following the series of reading-group sessions, Afterwork Readings is an anthology of migrant and domestic-worker literature. Published in four languages (Indonesian, English, Tagalog and Cantonese), the book is formed of poems and short stories: aware of the dangers of marking this as an exclusively Indonesian concern, the editors have been careful to expand its geographical range.

The foreword stresses that these stories intend to give a voice, without being patronising, to the community of workers. But here it starts to get confusing: which community of workers are Para Site and KUNCI referring to? Migrant domestic workers or migrant workers in general? And I can’t help wondering about the implications of having other writers pen the experiences of these workers: is an auto- biographical text about the successful writing career of Nh. Dini, a well-educated former flight attendant who married a French diplomat, really something a domestic worker who has had very little opportunity in life to begin with can relate to? Neither is there an explanation given for the number of texts (16 in total) written by Ruth Elynia S. Mabanglo, a retired professor of Filipino literature at University of Hawaii at Manoa, and Xu Lizhi, a poet and factory worker at Foxconn (a technology manufacturer) who came to prominence after his suicide at the age of twenty-four. Xu’s words are poignant and painful – ‘A space of ten square meters/Cramped and damp, no sunlight all year/Here I eat, sleep, shit, and think/Cough, get headaches, grow old, get sick but still fail to die’ – but these poems are the terrible story of a factory worker from mainland China, in mainland China.

In the effort to record (to use Para Site and KUNCI’s words) a ‘pluri-singular’ migrant experience, whereby the participants of the reading club are reminded that they are people, and not defined by or confined to the term ‘domestic’, Afterwork Readings seems to have tried to be inclusive, but at the same time neglected to dedicate a decent percentage of its 156 pages (out of the 24 authors, four are presently domestic workers) to the current reality of foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong – regardless of nationality. In short, Afterwork Readings loses a bit of focus and, in the end, leaves you asking who it is really for?

This article first appeared in the Summer 2016 issue of ArtReview Asia.